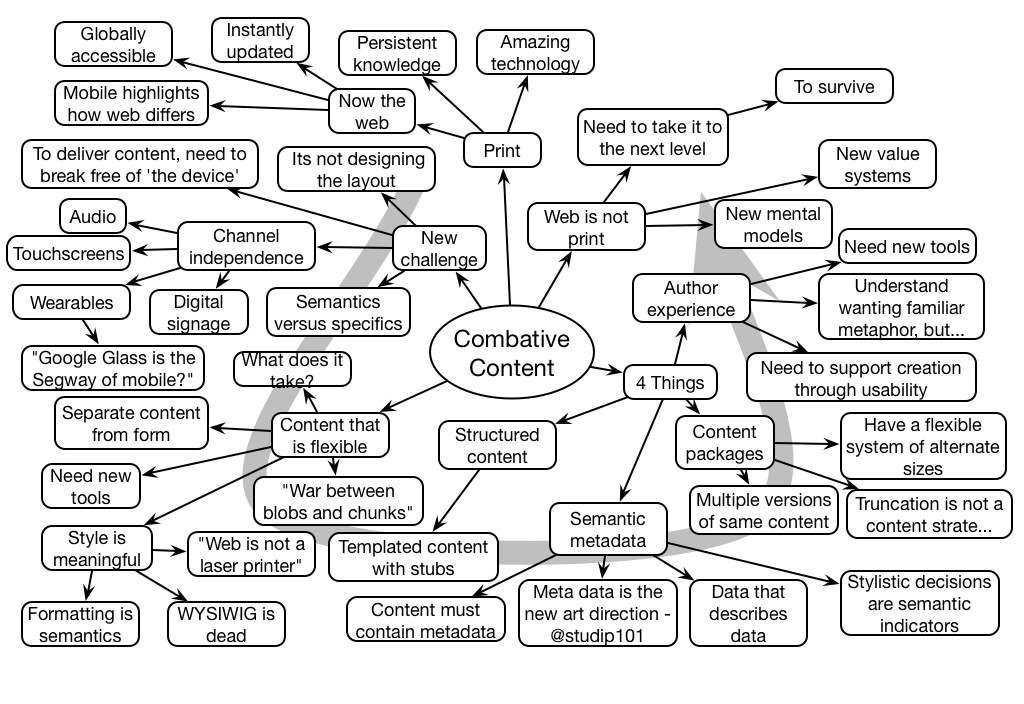

Karen McGrane evangelized good content architecture (a topic near to my heart), in a witty and clear keynote. With amusing examples and quotes, she brought out just how key it is to move beyond hard wired, designed content and start working on rule-driven combinations from structured chunks. Great stuff!

Archives for June 2014

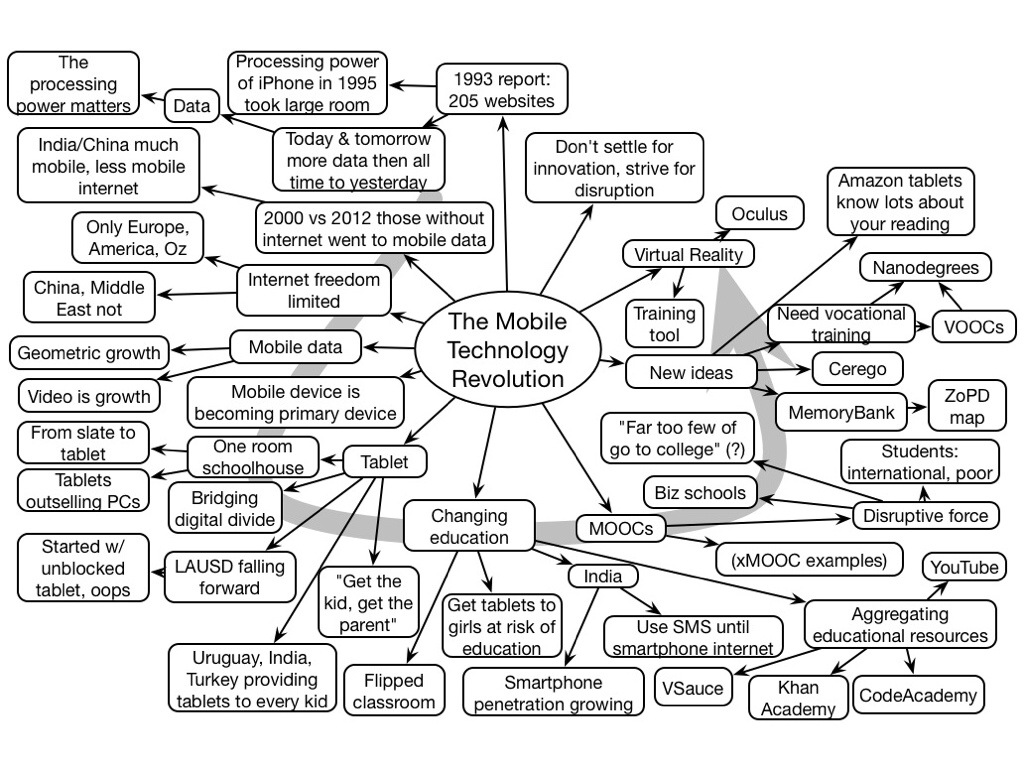

Larry Irving #mLearnCon Keynote Mindmap

THE Social Learning Handbook

I’ve been a fan of Jane Hart since I met her through Jay Cross and we joined together in the ITA (along with colleagues Harold Jarche and Charles Jennings). And I’d looked at the previous edition of her Social Learning Handbook, so it was on faith that I endorsed the new edition. So I took a deeper look recently, and my faith is justified; this is a great resource!

Jane has an admirable ability to cut through complex concepts and make them clear. She cites the best work out there when it is available, and comes with her own characterizations when necessary. The concepts are clear, illustrated, and comprehensible.

This isn’t a theoretical treatment, however. Jane has pragmatic checklists littered throughout as well as great suggestions. Jane is focused on having you succeed. Practical guidance underpins all the frameworks.

I’m all the more glad I recommended this valuable compendium. If you want to tap into the power of social learning, there is no better guide.

From the network, not your work

Too often, Learning & Development (L&D) is looking to provide all the answers. They work to get the information from SMEs, and create courses around it. They may also create performance support resources as well. And yet there are principled and pragmatic reasons why this doesn’t make sense. Here’s what I’m thinking.

On principle, the people working closest to the task are likely to be the most knowledgeable about it. The traditional role of information from the SME has been to support producing quality outputs, but increasingly there are tools that let the users create their own resources easily. The answer can come in the moment from people connected by networks, not having to go through an explicit process. And, as things are becoming more ambiguous and unique, this makes the accuracy to the context more likely as workers share their contexts and get targeted responses.

This doesn’t happen without facilitation. It takes a culture where sharing is valued, where people are connected, and have the skills to work well together. Those are roles L&D can, and should, play. Don’t assume that the network will be viable to begin with, or that people know how to work and play well together. Also don’t assume that they know how to find information on their own. The evidence is that these are skills that need to be developed.

The pragmatic reasons are those about how L&D has to meet more needs without resources. If people can self-help, L&D can invest resources elsewhere. I suggest that curation trumps creation, in that finding the answer is better than creating it, if possible.

When I talk about these possibilities, one of the reliable responses is “but what if they say the wrong thing?” And my response is that the network becomes self-correcting. Sure, networks require nurturing until they reach that stage, but again it’s a role for L&D. Initially, someone may need to be scrutinizing what comes through, and extolling experts to keep it correct, but eventually the network, with the right culture, support, and infrastructure, becomes a self-correcting and sustaining resource.

Work so that performers get their answers from the network, not from your work. When possible, of course.

#itashare

Curation trumps creation

In the past, it has been the role of L&D to ascertain the resources necessary to supporting performance in the organization. Finding the information, creating the resources, and making them available has often been a task that either results in training, or complements it. I want to suggest, however, that the time has changed and a new strategy may be more effective, at least in many instances.

Creating resources is hard. We’ve seen the need to revisit the principles of learning design because despite the pleas that “we know this stuff already”, there are still too many bad elearning courses out there. Similarly with job aids, there are skills involved in doing it right. Assuming those skills is a mistake.

There’s also the situation that creating resources is time consuming. The time spent doing this may be better spent in other approaches. There are plenty of needs that need to be addressed without finding more work.

On the flip side, there are now so many resources out there about so many things, that it’s not hard to find an answer. Finding good answers, of course, is certainly more problematic than just finding an answer, but there are likely answers out there.

The integration here is to start curating resources, not creating them. They might come internally, from the employees, or from external resources, but regardless of provenance, if it’s out there, it saves your resources for other endeavors.

The new mantra is Personal Knowledge Mastery, and while that’s for the individual, there’s a role for L&D here too: practicing ‘representative knowledge mastery’, as well as fostering PKM for the workforce. You should be monitoring feeds relevant to your role and those you’re responsible for facilitating. You need to practice it to be able to preach it, and you should be preaching it.

The point is to not be recreating resources that can be found, conserving your energy for those things that are business critical. One organization has suggested that they only create resources for internal culture, everything else is curated. Certainly only proprietary material should be the focus.

So, curate over create. Create when you have to, but only then. Finding good answers is more efficient than generating them.

#itashare

General or specific change

I was reflecting on the two books I recently wrote about, Scaling Up and Changing the Game, versus the cultural approach of the Learning Organization I wrote about years ago (and refer to regularly). The thing is that both of the new books are about choosing either a very specific needed change, whether determined by fiat or based upon something already working well, whereas the earlier work identified general characteristics that make sense. And my thought was when does each make sense? More importantly, what is the role of Learning & Development (L&D; which really should be P&D or Performance & Development) in each?

If an organization is in need of a shakeup, so that a particular unit is underperforming, or a significant shift in the game has been signaled by new competition or a technology/policy/social change, the targeted change makes sense. As I suggested, some of the required elements from the more general approach are implicit or explicit, such as facilitating communication. The role here for L&D, then, is to support the training required for executives leading the shift in terms of communicating and behaving, as well as ongoing coaching. Similarly for the behaviors of employees, and watching for signs of resistance, in general facilitating the shift. However, the locus of responsibility is the executive team in charge of the needed change.

On the other hand, if the organization is being moderately successful, but isn’t optimized in terms of learning, there’s a case for a more general shift. If the culture doesn’t have the elements of a real learning organization – safe to share, valuing diversity, openness to new ideas, time for reflection – then there’s a case to be made for L&D to lead the charge on the change. Let’s be clear, it cannot be done without executive buy-in and leadership, but L&D can be the instigator in this case. L&D here sells the benefits of the change, supports leadership in execution both by training if necessary and coaching, and again coaches the change.

Regardless, L&D should be instigating this change within their own unit. It’s going to lead to a more effective L&D unit, and there’re the benefits of walking the walk as a predecessor to talking the talk.

Ultimately, L&D needs to understand effective culture and the mechanisms to culture change, as well as facilitating social learning, performance consulting, information architecture, resource design, and of course formal learning design. There’re new roles and new skillsets to be mastered on the path to being an effective and strategic contributor to the organization, but the alternative is extinction, eh?

Changing Culture: Changing the Game

I previously wrote about Sutton & Rao’s Scaling up Excellence, and have now finished a quick read of Connors & Smith’s Change the Culture, Change the Game. Both books cover roughly the same area, but in very different ways. Sutton & Rao’s was very descriptive of the changes they observed and the emergent lessons. Connors & Smith, on the other hand, are very prescriptive. Yet both are telling similar stories with considerable overlap.

Let’s be clear, Connors & Smith have a model they want to sell you. You get the model up front, and then implementation tools in the second half. Of course, you aren’t supposed to actually try this without having their help. As long as you’re clear on this aspect of the book, you can take the lessons learned and decide whether you’d apply them yourself or use their support.

They have a relatively clear model, that talks about the results you want, the actions people will have to take to get to the results, the beliefs that are needed to guide those actions, and the experiences that will support those beliefs. They aptly point out that many change initiatives stop at the second step, and don’t get the necessity of the subsequent two steps. It’s a plausible story and model, where the actions, beliefs, and experiences are the elements that create the culture that achieves the results.

Like Kirkpatrick’s levels, the notion is that you start with the results you need, and work backward. Further, everything has to be aligned: you have to determine what actions will achieve the new results, and then what new beliefs can guide those new actions, and ultimately what experiences are needed to foster those new beliefs. You work rigorously to only focus on the ones that will make a difference, recognizing that too much will impact the outcome.

The second half talks about tools to foster these steps. There are management tools, leadership skills, and integration steps. There’s necessary training associated with these, and then coaching (this is the sales bit). It’s very formulaic, and makes it sound like close adherence to these approaches will lead to success. That said, there is a clear recognition that you need to continually check on how it’s going, and be active in making things happen.

And this is where there’s overlap with Sutton & Rao: it’s about ongoing effort, it requires accountability (being willing to take ownership of outcomes), people must be engaged and involved, etc. Both are different approaches to dealing with the same issue: working systematically to make necessary changes in an organization. And in both cases, the arguments are pretty compelling that it takes transparency and commitment by the leadership to walk the talk. It’s up to the executives to choose the needed change, but the empowerment to find ways to make that happens is diffused downward.

Whether you like the more organic approach of Sutton & Rao or the more formulaic model of Connors & Smith, you will find insight into the elements that facilitate change. For me, the synergy was nice to see. Now we’ll see if these are still old-school by comparison to Laloux’s Reinventing Organizations, that has received strong support from some colleagues I have learned to trust.

#itashare

Changing Culture: Scaling Up Excellence

I’ve found myself picking up books about how to change culture, as it seems to be the big barrier to a successful revolution. I’ve finished a quick read of Scaling Up Excellence, am in the midst of Change the Culture, Change the Game, and have Reinventing Organizations and Organize for Complexity (the latter two recommended by my colleague Harold Jarche) on deck. Here are my notes on the first.

Scaling Up Excellence is the work of two Stanford professors who have looked for years at what makes organizations succeed, particularly when they need to grow, or seed a transformation. They’ve had the opportunity to study a wide variety of companies, most as success stories, but they do include some cautionary tales as well. Fortunately, this doesn’t read like an academic book, and while it’s not equipped with formulas, there are overarching principles that have been extracted.

The overarching principle is that scaling is “a ground war, not an air war”. What they mean is that you can’t make a high level decision and expect change to happen. It requires hard work in the trenches. Leaders have to go in, figure out what needs to change, and then lead that change. Using a religious metaphor, they distinguish between Buddhist and Catholic approaches, where you’re either wanting everyone to follow the same template, or modify it to their unique situation. Some organizations need to replicate a particular customer experience (think fast food), whereas others will need to be more accommodating to unique situations (think high-end retailers).

There are some principles around scaling, such as getting mental buy-in, helping people see the bigger picture and how the near term necessities are tied into that, and that going slow initially may help things go better. An interesting one, to me, is that accountability is a key factor; you can’t have folks sit on the side lines, and no slackers (let alone those who undermine).

Another suite of principles include cutting the cognitive load to getting things done the right way, mixing together emotional issues with clever approach, connecting people. One important element is of course allegiance, where people believe in the organization and it’s clear the organization is also believing in the people. No one’s claiming this is easy, but they have lots of examples and guidance.

One really neat idea that I haven’t heard before was the concept of a pre-mortem, that is, imagining a period some time in the future and asking “why did it go right”, and also “why did it go wrong”. A nice way to distance oneself from the moment and reflect effectively on a proposed plan. If separate groups do this, the inputs can help address potential risks, and emphasize useful actions.

I worry a bit that it’s still ‘old school’ business, (more on that after I finish the book I’m currently reading and look to the two ‘new thinking’ books), but they do seem to be pushing the values of doing meaningful work and sharing it. A bit discursive, but overall I thought it insightful.

#itashare

Malicious metrics

Like others, I have been seduced by the “what X are you” quizzes on FaceBook. I certainly understand why they’re compelling, but I’ve begun to worry about just why they’re so prevalent. And I’m a wee bit concerned.

People like to know things about themselves. Years ago, when we built an adaptive learning system (it would profile you versus me, and then even if we took the same course we’d be likely to have a different experience), we realized we’d need to profile learning a priori. That is, we’d ask an initial suite of questions, and that’d prime the system. (And we intended this profiling to be a game, not a set of quiz questions). Ultimately that initial model built by the questions would get refined by learner behavior in the system (and we also intended a suite of interventions ‘layered’ on top that would help improve learner characteristics that were malleable).

The underlying mission given us by my CEO was to help learners understand themselves as learners, and use that to their advantage. So, in addition to asking the questions, we’d share with them what we’d learned about them as learners. The notion was what we irreverently termed the ‘Cosmo quiz’, those quizzes that appeared in Cosmopolitan magazine about “how good a Y” you are, where one takes quizzes and then adds up the score.

Fast forward to now, and I began to wonder about these quizzes. They seem cute and harmless, but without seeing all the possible outcomes, it certainly seemed like it might not take that many questions to determine which one you’d qualify as. Yes, in good test design, you ask a question a number of times to disambiguate. But it occurred to me that you could use fewer questions (and the outcomes are always written intriguingly so you don’t necessarily mind which you become), and then wonder what are the other questions being used for. And the outcomes here don’t really matter!

So, it’d be real easy to insert demographic questions and use that information (presumably en masse) to start profiling markets. If you know other information about these people, you can start aggregating data and mining for information. One question I saw, for instance, asked you to pick which setting (desert, jungle, mountain, city), etc. Could that help recommend vacations to you?

When I researched these quizzes, rather than finding concerns about the question data, instead I found that much more detailed information about your account was allowed to be passed from Facebook to the quiz hoster. Which is worse! Even if not, I begin to worry that while they’re fun, what’s the motivation to keep creating new ones? What’s the business relationship? And I think it’s data.

Now, getting better data means you might get more targeted advertising. And that might be preferable than random (I’ve seen some pretty funny complaints about “what made them think this was for me”). But I don’t feel like giving them that much insight. So I’m not doing any more of those. I don’t think they really know what animal/movie character/color/fruit/power tool I am. If you want to know, ask me.

From Content to Experience

A number of years ago, I said that the problem for publishers was not going from text to content (as the saying goes), but from content to experience. I think elearning designers have the same problem: they are given a knowledge dump, and have to somehow transform that into an effective experience. They may even have read the Serious eLearning Manifesto, and want to follow it, but struggle with the transition or transformation. What’s a designer to do?

The problem is, designers will be told, “we need a course on this”, and given a dump of Powerpoints (PPTs), documents (PDFs), and maybe access to a subject matter expert (SME). This is all about knowledge. Even the SME, unless prompted carefully otherwise, will resort to telling you the knowledge they’ve learned, because they just don’t have access to what they know. And this, by itself, isn’t a foundation for a course. Processing the knowledge, comprehending it, presenting it, and then testing on acquisition (e.g. what rapid elearning tools make easy), isn’t going to lead to a meaningful outcome. Sorry, knowledge isn’t the same as ability to perform.

And this ignores, of course, whether this course is actually needed. Has anyone checked to see that if the skills associated with this knowledge have a connection with a real workplace performance issue? Is the performance need a result of a lack of skills? And is this content aligned to that skill? Too often folks will ask for a course on X when the barrier is something else. For instance, if the content is a bunch of knowledge that somehow you’re to magically put in someone’s head, such as product information or arbitrary rules, you’re far better off putting that information in the world than trying to put it in the head. It’s really hard to get arbitrary information in the head. But let’s assume that there is a core skill and workplace need for the sake of this discussion.

The key is determining what this knowledge actually supports doing differently. The designer needs to go through that content and figure out what individuals will be able to do that they can’t do now (that’s important), and then develop practice doing that. This is so important that, if what they’ll be able to do differently, isn’t there, there should be push back. While you can talk to the SME (trying to get them to talk in terms of decisions they can make instead of knowledge), you may be better off inferring the decisions and then verifying and refining with the SME. If you have access to several SMEs, better yet get them in a room together and just facilitate until they come up with the core decisions, but there are many situations where that’s not feasible.

Once you have that key decision, the application of the skill in context, you need to create situations where learners can practice using it. You need to create scenarios where these decisions will play out. Even just better written multiple choice questions that have: story setting, situation precipitating decision, decision alternatives that are ways in which learners might go wrong, consequences of the decisions, and feedback. These practice attempts are the core of a meaningful learning experience. And there’s even evidence that putting problems up front or at core is a valuable practice. You also want to have sufficient practice not just ’til they get it right, but until they have a high likelihood of not getting it wrong.

One thing that might not be in the PDFs and PPTs are examples. It’s helpful to get colorful examples of someone using information to successfully solve a problem, and also cases where they misapplied it and failed. Your SME should be able to help you here, telling you engaging stories of wins and losses. They may be somewhat resistant to the latter; worst case have them tell them about someone else.

The content in the PDFs and PPTs then gets winnowed down into just the resource material that helps the learner actually able to do the task, to successfully make the decision. Consider having the practice set in a story, and the content is available through the story environment (e.g. casebooks on the shelves for examples, a ‘library’ for concepts). But even if you present the (minimized) content and then have practice, you’ve shifted from knowledge dump/test to more of a flow of experience. The suite of meaningful practice, contextualized well and made meaningful with a wee bit of exaggeration and careful alignment with learner’s awareness, is the essence of experience.

Yes, there’s a bit more to it than that, but this is the core: focus on do, not dump. And, once you get in the habit, it shouldn’t take longer, it just takes a change in thinking. And even if it does, the dump approach isn’t liable to lead to any meaningful learning, so it’s a waste of time anyway. So, create experiences, not content.