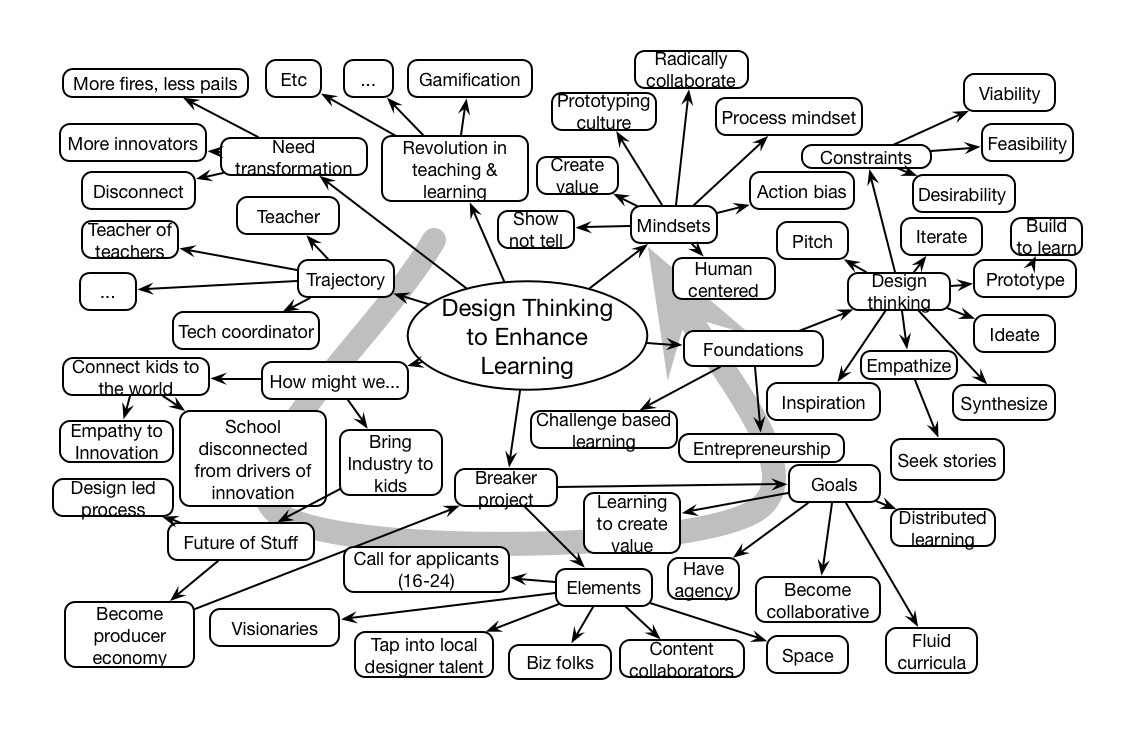

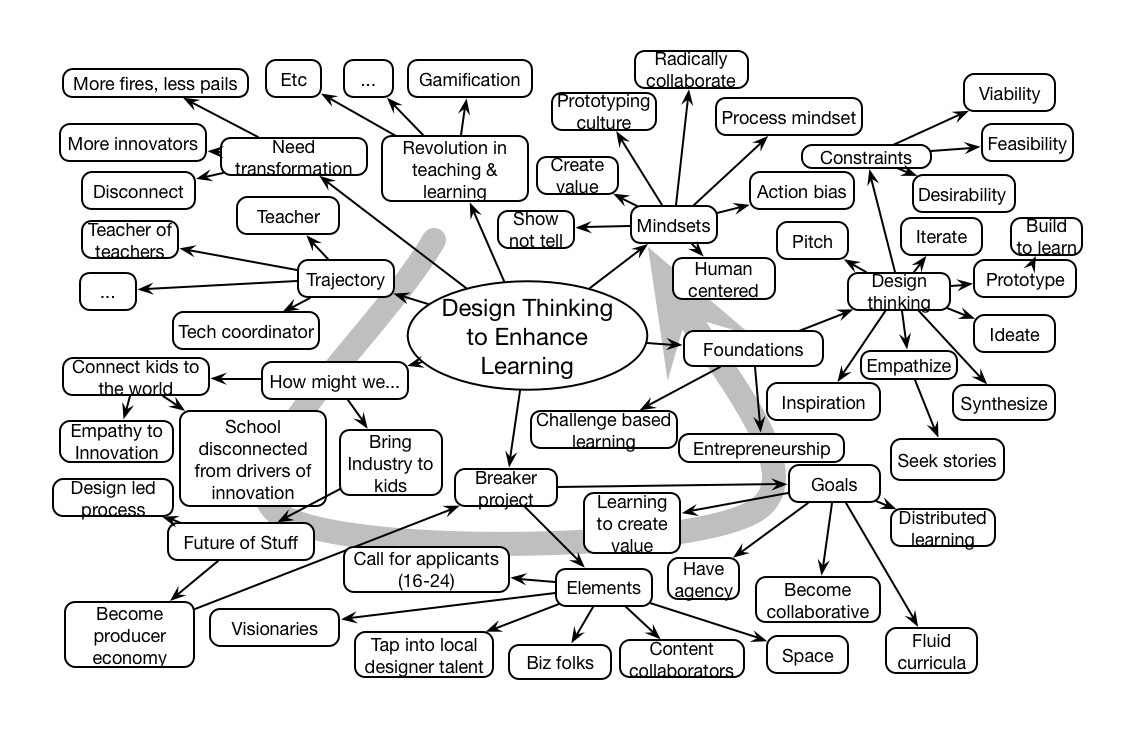

Juliette LaMontagne closed the Learning Solutions conference with the compelling story of the Breaker project, connecting kids to real world experiences.

Clark Quinn’s Learnings about Learning

by Clark 2 Comments

Juliette LaMontagne closed the Learning Solutions conference with the compelling story of the Breaker project, connecting kids to real world experiences.

by Clark 3 Comments

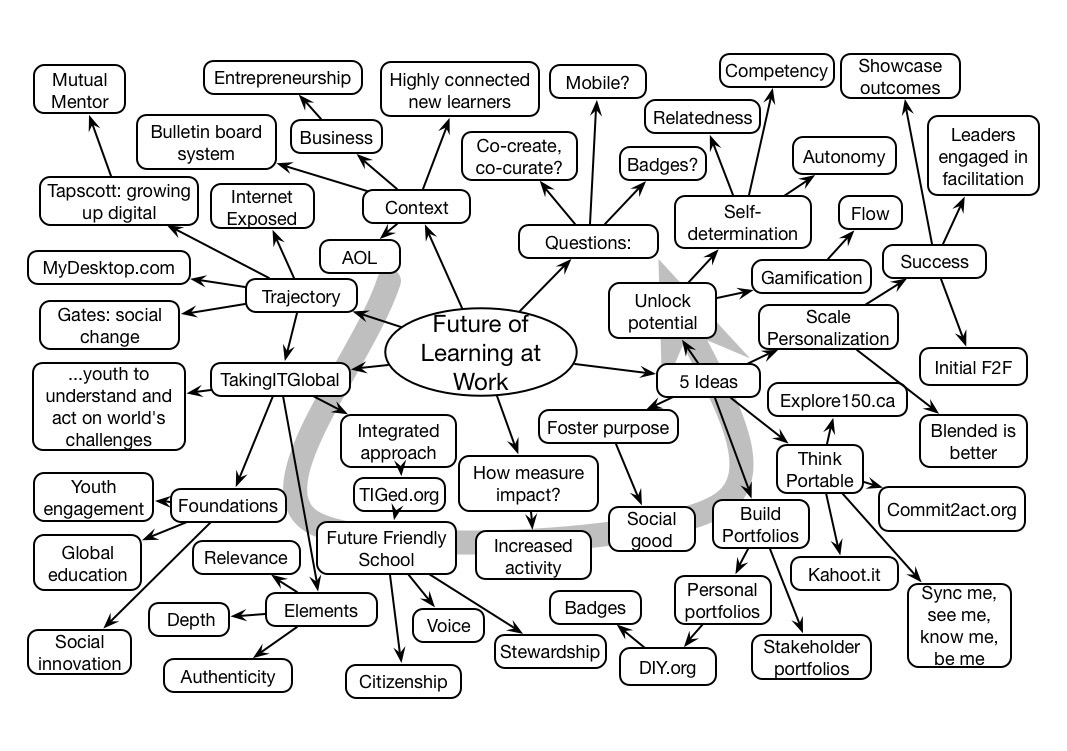

Michael Furdyk gave an inspiring talk this morning about his trajectory through technology and then five ideas that he thought were important elements in the success of the initiatives he had undertaken. He gave lots of examples and closed with interesting questions about how we might engage learners through badges, mobile, and co-creation.

by Clark 2 Comments

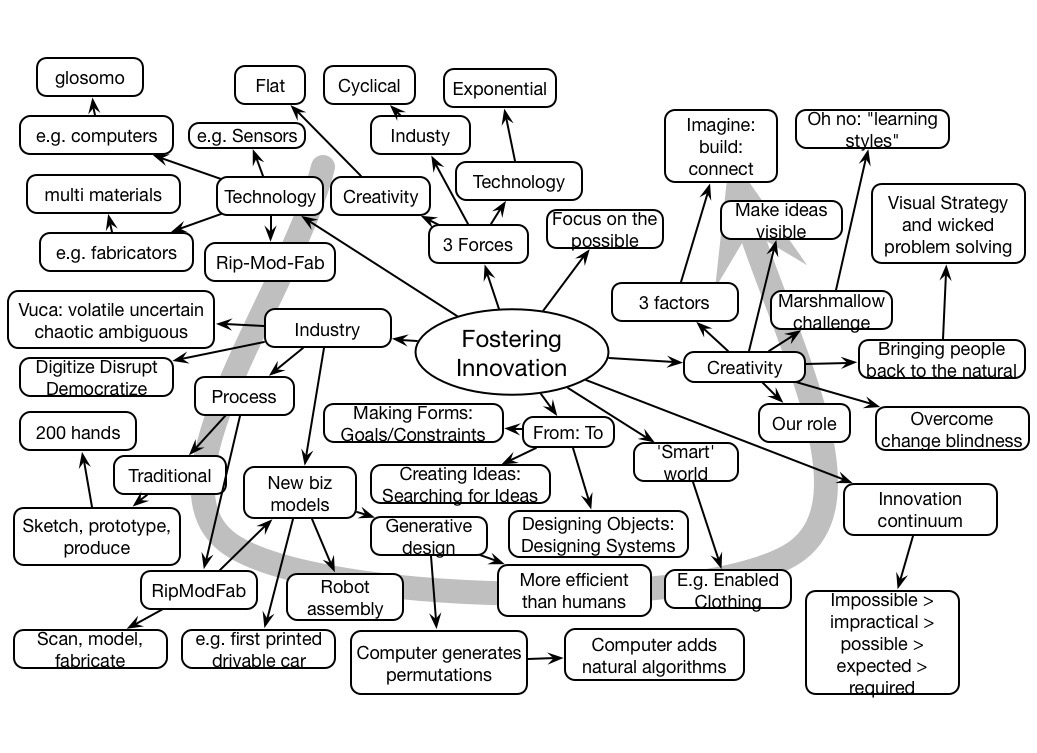

Tom Wujec gave a discursive and well illustrated talk about how changes in technology were changing industry, ultimately homing in on creativity. Despite a misstep mentioning Kolb’s invalid learning styles instrument, it was entertaining and intriguing.

A couple of times last year, firms with some exciting learning tools approached me to talk about the market. And in both cases, I had to advise them that there were some barriers they’d have to address. That was brought home to me in another conversation, and it makes me worry about the state of our industry.

So the first tool is based upon a really sound pedagogy that is consonant with my activity-based learning approach. The basis is giving learners assignments very much like the assignments they’ll need to accomplish in the workplace, and then resourcing them to succeed. They wanted to make it easy for others to create these better learning designs (as part of a campaign for better learning). The only problem was, you had to learn the design approach as well as the tool. Their interface wasn’t ready for prime time, but the real barrier was getting people to be able to use a new tool. I indicated some of the barriers, and they’re reconsidering (while continuing to develop content against this model as a service).

The second tool supports virtual role plays in a powerful way, having smart agents that react in authentic ways. And they, too, wanted to provide an authoring tool to create them. And again my realistic assessment of the market was that people would have trouble understanding the tool. They decided to continue to develop the experiences as a service.

Now, these are somewhat esoteric designs, though the former should be the basis of our learning experiences, and the latter would be a powerful addition to support a very common and important type of interaction. The more surprising, and disappointing, issue came up with a conversation earlier this year with a proponent of a more familiar tool.

Without being specific (I’ve not received permission to disclose the details in all of the above), this person indicated that when training a popular and fairly straightforward tool, that the biggest barrier wasn’t the underlying software model. I was expecting that too much of training was based upon rote assignments without an underlying model, and that is the case, but instead there was a more fundamental barrier: too many potential users just didn’t have sufficient computer skills! And I’m not talking about programming code, but instead fundamental understandings of files and ‘styles‘ and other core computing elements just were not present in sufficient quantities in these would-be authors. Seriously!

Now I’ve complained before that we’re not taking learning design seriously, but obviously we’re compounded by a lack of fundamental computer skills. Folks, this is elearning, not chalk learning, not chalk talk, not edoing, etc. If you struggle to add new apps on your computer, or find files, you’re not ready to be an elearning developer.

I admit that I struggle to see how folks can assume that without knowledge of design, nor knowledge of technology, that they can still be elearning designers and developers. These tools are scaffolding to allow your designs to be developed. They don’t do design, nor will they magically cover up for lacks of tech literacy.

So, let’s get realistic. Learn about learning design, and get comfortable with tech, or please, please, don’t do elearning. And I promise not to do music, architecture, finance, and everything else I’m not qualified to. Fair enough?

by Clark 3 Comments

The other day, I was wondering about the possibilities of removing mandatory courses. Ok, maybe not mandated compliance, but any others. And then a colleague took it further, and I like it. So what are we talking about?

I was thinking that, if you give people a meaningful mission (ala Dan Pink’s Drive), the learner (assuming reasonable self-learning skills, a separate topic), they would take responsibility for the learning they needed. We could have courses around, or maybe await their desires and point them to outside resources, etc, unless it’s specifically internal. That is, we become much more pull (from the user) than push (from us).

However, my colleague Mark Britz took it further. He argued that instead of not making them go, instead we’d charge them what it cost to provide the learning! That is, if folks wanted training or webinars or…, they’d pay for the privilege. As he put it, if requests for elearning, being cautious about signing up, etc happened: “I couldn’t be happier!”

His point is that it would drive people to more workflow learning, more social and shared learning, etc. And that’s a good thing. I might couple that with some way to make sure they knew how to work, play, and learn well together, but it’s the different view that’s a needed jumpstart.

It’s a refreshing twist on the ‘if we build it it is good’ sort of mentality, and really helps focus the L&D unit on doing things that will significantly improve outcomes for others. If you can make a meaningful impact, people will have to pay for your assistance. You want change? You’ll pay but it’ll be worth it.

If we’re going to kick off a revolution, we need to rethink what we’re about and how we’re doing it. Mark’s upended view is a necessary kick in the status quo to get us to think anew about what we’re doing and why.

I recommend you read his original post.

A couple of weeks ago, I was riffing on sensors: how mobile devices are getting equipped with all sorts of new sensors and the potential for more and what they might bring. As part of that discussion was a brief mention of sensor nets, how aggregating all this data could be of interest too. And low and behold, a massive example was revealed last week.

The context was the ‘spring forward’ event Apple held where they announced their new products. The most anticipated one was the Apple Watch (which was part of the driving behind my post on wearables), the new iConnected device for your wrist. The second major announcement was their new Macbook, a phenomenally thin new laptop with some amazing specs on weight and screen display, as well as some challenging tradeoffs.

One announcement that was less noticed was the announcement of a new research endeavor, but I wonder if it isn’t the most game-changing element of them all. The announcement was ResearchKit, and it’s about sensor nets.

So, smartphones have lots of sensors. And the watch will have more. They can already track a number of parameters about you automatically, such as your walking. There can be more, with apps that can ask about your eating, weight, or other health measurements. As I pointed out, aggregating data from sensors could do things like identify traffic jams (Google Maps already does this), or collect data like restaurant ratings.

What Apple has done is to focus specifically on health data from their HealthKit, and partner with research hospitals. What they’re saying to scientists is “we’ll give you anonymized health data, you put it to good use”. A number of research centers are on board, and already collecting data about asthma and more. The possibility is to use analytics that combine the power of large numbers with a bunch of other descriptive data to be able to investigate things at scale. In general, research like this is hard since it’s hard to get large numbers of subjects, but large numbers of subjects is a much better basis for study (for example, the China-Cornell-Oxford Project that was able to look at a vast breadth of diet to make innovative insights into nutrition and health).

And this could be just the beginning: collecting data en masse (while successfully addressing privacy concerns) can be a source of great insight if it’d done right. Having devices that are with you and capable of capturing a variety of information gives the opportunity to mine that data for expected, and unexpected, outcomes.

A new iDevice is always cool, and while it’s not the first smart watch (nor was the iPhone the first smartphone, the iPad not the first tablet, nor the iPod the first music play), Apple has a way of making the experience compelling. Like with the iPad, I haven’t yet seen the personal value proposition, so I’m on the fence. But the ability to collect data in a massive way that could support ground-breaking insights and innovations in medicine? That has the potential for affecting millions of people around the world. Now that is impact.

by Clark 11 Comments

There’s been quite a bit of flurry about Design Thinking of late (including the most recent #lrnchat), and I’m trying to get my around what’s unique about it. The wikipedia entry linked above helps clarify the intent, but is there any there there?

It helps to understand that I’ve been steeped in design approaches since at least the 80’s. Herb Simon’s Sciences of the Artificial argued, essentially, that design is the quintessential human activity. And my grad school experience was in a research lab focused on interface design. Process was critical, and when I was subsequently teaching interface design, I was tracking new initiatives like situated design and participatory design, anthropological efforts designed to get closer to the ‘customer’.

In addition to being somewhat obsessive about learning how people learn, and as a confirmed geek continually exploring new technology, I also got interested in design processes beyond interface design. As my passion was designing learning technology solutions to meet real needs, I explored other design approaches to look for universals. Along the way I looked at industrial, graphic, architectural, software, and other design disciplines. I also read the psychological research on our cognitive limitations and design approaches. (I made a small bit of my career on bringing the advances in HCI, which was more advanced in process, to ed tech.)

The reason I mention this is that the elements of Design Thinking: being open minded, diverging before converging, using teams, empathy for the customer, etc, all strike me as just good design. It’s not obvious to me whether it gets into the nuances (e.g. the steps in the Wikipedia article don’t allow me to see whether they do things like ensure that everyone takes time to brainstorm on their own before coming together; an important step to prevent groupthink), but at the granularity I’ve seen, it seems to be quite good. You mean everyone isn’t already both aware of and using this? Apparently not.

So in that respect, Design Thinking is a win. If adding a label to a systematized compendium of good practices will raise awareness, I’m all for it. And I’m willing to have my consciousness raised that there’s more to it, because as a proponent of design, I’m glad to see that folks are taking steps to help design get better and will be thrilled if it adds something new.

by Clark 3 Comments

Well, some more travels are imminent, so I thought I’d update you on where the Quinnovation road show would be on tour this spring:

So, if you’re at one of these, do come up and introduce yourself and say hello!

I’m a big fan of the mantras of (variously) ‘show your work‘ or ‘working out loud‘. I think that the notion of showing what you’re doing helps other work with you to make it better, or learn from you if you do well. This contributes to the success of the ‘coherent organization‘, where information flows in ways that are aligned with the goals of the organization. But I want to extend it a bit.

Let me use an analogy: remember when your teacher asked you to ‘show your work’? It wasn’t just the product, but the intermediate steps, and I’m sure that’s what Jane Bozarth is implying. But it’s too easy for people to think it’s about making your work product available instead of one that’s marked up with the underlying thinking. In user interface work it was known as ‘design rationale’, where you kept a track of the assumptions and decisions along the way.

I’ve termed this ‘cognitive annotation’ at various points (what, me create new phrases?). And it’s really important for a number of reasons:

I have a couple of guilty pleasures that make this point quite clearly. Lee Child is a writer who has a character called Jack Reacher (hence the movie, pretty entertaining despite the wrong physical type to play the lead role). This character is ex-military police and quite capable in challenging situations. What makes this series more than usually interesting is that the character regularly outlines the situation, the thinking behind it, and the resulting actions taken. In doing so, it’s often a format like “most people think X, but because of Y, Z is a better choice”.

Another place this shows up is the recently finished television series Burn Notice. In this case, a ‘burned’ spy is forced to freelance, and regularly gets in situations where again, the conventional wisdom is debunked. With a regular approach of a ‘sting’, along with a dry humor and some larger-than-life characters, it’s fun, and interesting because of the underlying thinking that explains the choices made.

Granted, neither of these are situations I have any interest in being in, but it’s a nice twist and makes the stories more interesting.

In the real world, it can be hard to share underlying thinking if it’s a Miranda organization, but the benefits suggest that the effort to achieve a culture where such openness is ‘safe’ is a worthwhile endeavor. At least, that’s my thinking.

#itashare