I recently came across an article ostensibly about branching scenarios, but somehow the discussion largely missed the point. Ok, so I can be a stickler for conceptual clarity, but I think it’s important to distinguish between different types of scenarios and their relative strengths and weaknesses.

So in my book Engaging Learning, I was looking to talk about how to make engaging learning experiences. I was pushing games (and still do) and how to design them, but I also wanted to acknowledge the various approximations thereto. So in it, I characterized the differences between what I called mini-scenarios, linear scenarios, and contingent scenarios (this latter is what’s traditionally called branching scenarios). These are all approximations to full games, with various tradeoffs.

At core, let me be clear, is the need to put learners in situations where they need to make decisions. The goal is to have those decisions closely mimic the decisions they need to make after the learning experience. There’s a context (aka the story setting), and then a specific situation triggers the need to make a decision. And we can deliver this in a number of ways. The ideal is a simulation-driven (aka model-driven or engine-driven) experience. There’s a model of the world underneath that calculates the outcomes of your action and determines whether you’ve yet achieved success (or failure), or generates a new opportunity to act. We can (and should) tune this into a serious game. This gives us deep experience, but the model-building is challenging and there are short cuts.

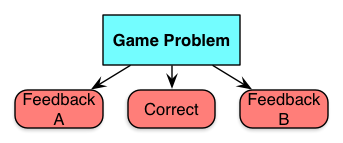

In mini-scenarios, you put the learner in a setting with a situation that precipitates a decision. Just one, and then there’s feedback. You could use video, a graphic novel format, or just prose, but the game problem is a setting and a situation, leading to choices. Similarly, you could have them respond by selecting option A B or C, or pointing to the right answer, or whatever. It stops there. Which is the weakness, because in the real world the consequences are typically more complex than this, and it’s nice off the learning experience reflects that reality. Still, it’s better than knowledge test. Really, these are just a better written multiple choice question, but that’s at least a start!

In mini-scenarios, you put the learner in a setting with a situation that precipitates a decision. Just one, and then there’s feedback. You could use video, a graphic novel format, or just prose, but the game problem is a setting and a situation, leading to choices. Similarly, you could have them respond by selecting option A B or C, or pointing to the right answer, or whatever. It stops there. Which is the weakness, because in the real world the consequences are typically more complex than this, and it’s nice off the learning experience reflects that reality. Still, it’s better than knowledge test. Really, these are just a better written multiple choice question, but that’s at least a start!

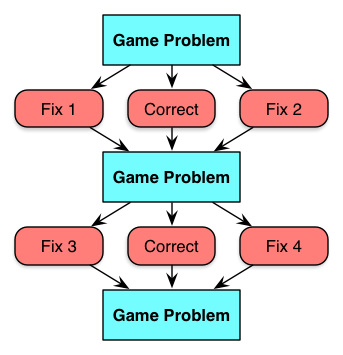

Linear scenarios are a bit more complex. There are a series of game problems in the same context, but whatever the player chooses, the right decision is ultimately made, leading to the next problem. You use some sort of sleight of hand, such as “a supervisor catches the mistake and rectifies it, informing you…” to make it all ok. Or, you can terminate out and have to restart if you make the wrong decision at any point. These are a step up in terms of showing the more complex consequences, but are a bit unrealistic. There’s some learning power here, but not as much as is possible. I have used them as sort of multiple mini-scenarios with content in between, and the same story is used for the next choice, which at least made a nice flow. Cathy Moore suggests these are valuable for novices, and I think it’s also useful if everyone needs to receive the same ‘test’ in some accreditation environment to be fair and balanced (though in a competency-based world they’d be better off with the full game).

Linear scenarios are a bit more complex. There are a series of game problems in the same context, but whatever the player chooses, the right decision is ultimately made, leading to the next problem. You use some sort of sleight of hand, such as “a supervisor catches the mistake and rectifies it, informing you…” to make it all ok. Or, you can terminate out and have to restart if you make the wrong decision at any point. These are a step up in terms of showing the more complex consequences, but are a bit unrealistic. There’s some learning power here, but not as much as is possible. I have used them as sort of multiple mini-scenarios with content in between, and the same story is used for the next choice, which at least made a nice flow. Cathy Moore suggests these are valuable for novices, and I think it’s also useful if everyone needs to receive the same ‘test’ in some accreditation environment to be fair and balanced (though in a competency-based world they’d be better off with the full game).

Then there’s the full branching scenario (which I called contingent scenarios in the book, because the consequences and even new decisions are contingent on your choices). That is, you see different opportunities depending on your choice. If you make one decision, the subsequent ones are different. If you don’t shut down the network right away, for instance, the consequences are different (perhaps a breach) than if you do (you get the VP mad). This, of course, is much more like the real world. The only difference between this and a serious game is that the contingencies in the world are hard-wired in the branches, not captured in a separate model (rules and variables). This is easier, but it gets tough to track if you have too many branches. And the lack of an engine limits the replay and ability to have randomness. Of course, you can make several of these.

Then there’s the full branching scenario (which I called contingent scenarios in the book, because the consequences and even new decisions are contingent on your choices). That is, you see different opportunities depending on your choice. If you make one decision, the subsequent ones are different. If you don’t shut down the network right away, for instance, the consequences are different (perhaps a breach) than if you do (you get the VP mad). This, of course, is much more like the real world. The only difference between this and a serious game is that the contingencies in the world are hard-wired in the branches, not captured in a separate model (rules and variables). This is easier, but it gets tough to track if you have too many branches. And the lack of an engine limits the replay and ability to have randomness. Of course, you can make several of these.

So the problem I had with the article that triggered this post is that their generic model looked like a mini-scenario, and nowhere did they show the full concept of a real branching scenario. Further, their example was really a linear scenario, not a branching scenario. And I realize this may seem like an ‘angels dancing on the head of a pin’, but I think it’s important to make distinctions when they affect the learning outcome, so you can more clearly make a choice that reflects the goal you are trying to achieve.

To their credit, that they were pushing for contextualized decision making at all is a major win, so I don’t want to quibble too much. Moving our learning practice/assessment/activity to more contextualized performance is a good thing. Still, I hope this elaboration is useful to get more nuanced solutions. Learning design really can’t be treated as a paint-by-numbers exercise, you really should know what you’re doing!

A nice overview of the different types of simulation, Clark. As always, if I pop up, it’s to disagree somewhere. This time, it’s to argue that there’s something between contingent scenarios and full simulation, that I think is often better than real simulation. I called it outcome-driven simulation. I made a sketch for comparison, along the lines of yours: http://cs.northwestern.edu/~riesbeck/dynamic-scenes.png

The key idea is that you first author the meaningfully different situations, or scenes, that can occur in your domain. Each scene has its own coherent set of issues and possible actions. Then you author rules to select the most appropriate scene to go to, based on the actions taken. Structurally, you have a graph, richer than your linear scenarios, but not an unbounded tree like your contingent scenarios.

There’s room for a fair amount of complexity here. Rules can accommodate multiple action choices per scene and scene variables to hold details such as money spent so far. These provide a history and some individualization to the simulation path, but are not meant to encode a true simulation model.

In a true simulation, lots of things can result from certain choices, not all of them that interesting to explore. With the outcome-driven approach, you can maximize the exploration of interesting situations and challenges.

A few slides on the motivation here: http://cs.northwestern.edu/~riesbeck/outcome-driven-simulation.pdf

A commercial application: https://echristensenblog.wordpress.com/technology-solutions/dynamic-scene-adapter/

Chris, always welcome your insightful feedback; so please don’t hesitate! You’re absolutely right that the market has changed since I first made these distinctions, and there are indeed some solutions that fit in-between branching scenarios and full simulations. NexLearn’s SimWriter tool allows variables to be passed on from earlier branches to later to influence outcomes, and Avalanche ST has some local processing available at particular locations, very much like your ‘scenes’. Actually, when I talk about designing serious games (e.g. in Engaging Learning), I very much focus on only the necessary underlying engine to create and sequence the desired decisions. Yes, you can learn from a full simulation, but I talk about creating first a scenario that requires the right decisions, and then tuning the experience to get an engaging series of important decisions (leveraging Sid Maier’s “a game is a series of interesting decisions” for my evil purposes). Your approach nicely combines a good design approach with a practical implementation plan. Thanks for sharing!

Thanks for the post Clark. I’ve been using what we call ‘mini-sims’ essentially your linear simulations, then more nuanced branched scenarios (your contingent scenarios) as part of our blended learning solutions. We’ve been trying to develop more efficient ways to create them looking at BranchTracker for the mini-sims for example.

For the more complex branched scenarios we currently use twine to plan and then create them using articulate or storyline but I find both so limited in terms of using variables for really interesting/personalised options. I appreciate the mention of SimWriter which I hadnt heard of and will check out. The other thing we’re really enjoying playing with is posing scenarios via simple elearning and then debating out responses in discussion forums which is great in terms of seeding community discussion.

Arun, yes, in situations where you do have social learning possibilities, having some ambiguity and discussion is a great opportunity. Thanks for sharing.