For sins in my past, I’ve been thinking about assessments a bit lately. And one of the biggest problems comes from trying to find solutions that are meaningful yet easy to implement. You can ask learners to develop meaningful artifacts, but getting them assessed at scale is problematic. Mostly, auto-marked stuff is used to do trivial knowledge checks. Can we do better.

To be fair, there are more and more approaches (largely machine-learning powered), that can do a good job of assessing complex artifacts, e.g. writing. If you can create good examples, they can do a decent job of learning to evaluate how well a learner has approximated it. However, those tools aren’t ubiquitous. What is are the typical variations on multiple choice: drag and drop, image clicks, etc. The question is, can we use these to do good things?

To be fair, there are more and more approaches (largely machine-learning powered), that can do a good job of assessing complex artifacts, e.g. writing. If you can create good examples, they can do a decent job of learning to evaluate how well a learner has approximated it. However, those tools aren’t ubiquitous. What is are the typical variations on multiple choice: drag and drop, image clicks, etc. The question is, can we use these to do good things?

I want to say yes. But you have to be thinking in a different way than typical. You can’t be thinking about testing knowledge recognition. That’s not as useful a task as knowledge retrieval. You don’t want learners to just have to discriminate a term, you want them to use the knowledge to do something. How do we do that?

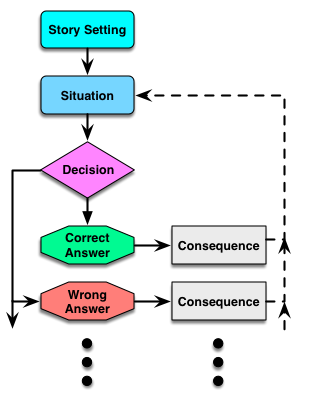

In Engaging Learning, amongst other things I talked about ‘mini-scenarios’. These include a story setting and a required decision, but they’re singular, e.g. they don’t get tied to subsequent decisions. And this is just a better form of multiple choice!

So, for example, instead of asking whether an examination requires an initial screening, you might put the learner in the role of someone performing an examination, and have alternative choices of action like beginning the examination, conducting an initial screening, or reviewing case history. The point is that the learner is making choices like the ones they’ll be making in real practice!

Note that the alternatives aren’t random; but instead represent ways in which learners reliably go wrong. You want to trap those mistakes in the learning situation, and address them before they matter! Thus, you’re not recognizing whether it’s right or not, you’re using that information to discriminate between actions that you’d take. It may be a slight revision, but it’s important.

Further, you have the consequences of the choice play out: “your examination results were skewed because…and this caused X”. Then you can give the principled feedback (based upon the model).

There are, also, the known obvious things to do. That is, don’t have any ‘none of the above’ or ‘all of the above’. Don’t make the alternatives obviously wrong. And, as Donald Clark summarizes, have two alternatives, not three. But the important thing, to me, is to have different choices based upon using the information to make decisions, not just recognizing the information amongst distractors. And capturing misconceptions.

These can be linked into ‘linear’ scenarios (where the consequences make everything right so you can continue in a narratively coherent progression) or branching, where decisions take you to different new decisions dependent on your choice. Linear and branching scenarios are powerful learning. They’re just not always necessary or feasible.

And I certainly would agree that we’d like to do better: link decisions and complex work products together into series of narratively contextualized settings, combining the important types of decisions that naturally occur (ala Schank’s Goal Based Scenarios and Story-Centered Curriculum and other similar approaches). And we’re getting tools that make this possible. But that requires some new thinking. This is an interim step that, if you get your mind around it, sets you up to start wanting more.

Note that the thinking here also covers a variety of interaction possibilities, again drag’n’drop, image links, etc. It’s a shift in thinking, but a valuable one. I encourage you to get your mind around it. Better practice, after all, is better learning.

Leave a Reply