I received some feedback on my post on Organizational Knowledge Mastery. The claim was that if you trusted to human sensing, you’d be only able to track what’s become common knowledge, and that doesn’t provide the necessary competitive advantage. The extension was that you needed market analytics to see new trends. And it caused me to think a little deeper.

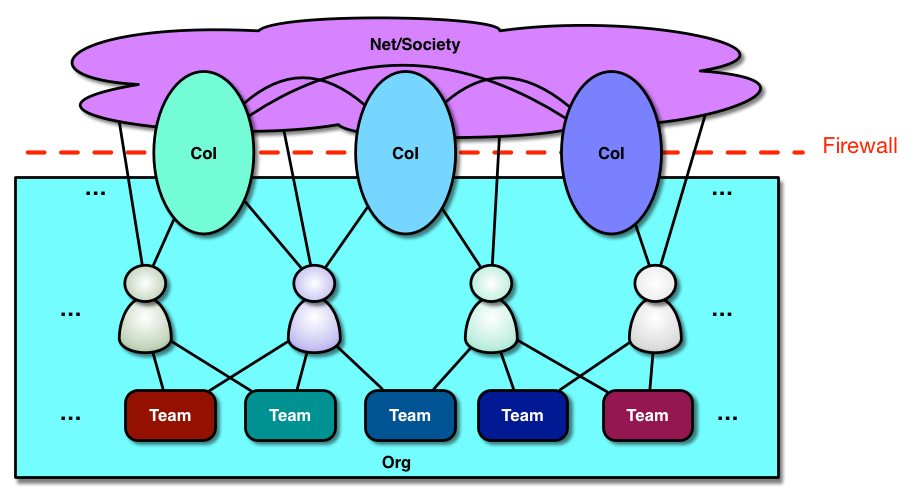

I‘m thinking that the individuals in the organization, in their sensing/sharing, are tracking things before it becomes common knowledge. If people are actively practicing ongoing sensemaking and sharing internally and finding resonance, that can develop understanding before it becomes common knowledge. They’ve expertise in the area, and so that shared sense making should precede what emerges as common knowledge. Another way to think about it is to ask where the knowledge comes from that ​becomes the common knowledge?

And I‘m thinking that market analytics aren‘t going to find the new, because by definition no one knows that to look for yet. Or at least part of the new. To put it another way, the qualitative (e.g. semantic) changes aren‘t going to be as visible to machine sensing as to human (Watson notwithstanding). The emerging reality is human-machine hybrids are more powerful than either alone, but each alone finds ​different things. So there were things in protein-folding that machines found, but other things that humans playing protein-folding games found. I have no problem with market data also, but I definitely think that the organization benefits to the extent that it supports human sense-making as well. Different insights from different mechanisms.

And I also think a culture for agility comes from a different ‘space‘ than does a rabid focus on numerics. A mindset that accommodates both is needed. I don’t think they’re incommensurate. I‘m kind of suspicious of dual operating systems versus a podular approach, as I suspect that the hierarchical activities will be automated and/or outsourced, but I’m willing to suspend my criticism until shown otherwise.

So, still pondering this, and welcome your feedback.