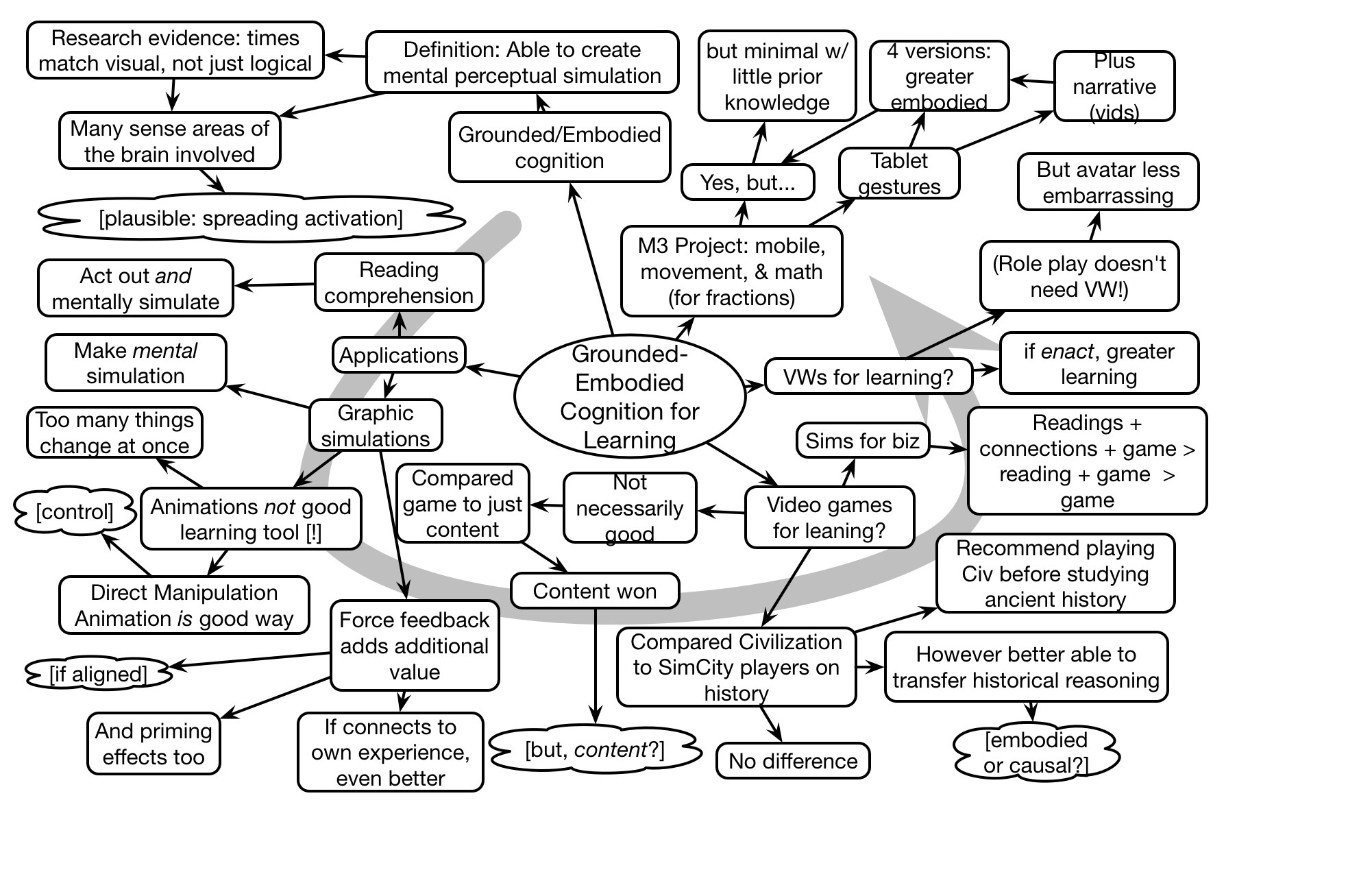

Designing learning is a probability game. To paraphrase Dorothy Parker, you can lead a learner to learning, but you can’t make them think. What I mean is that the likelihood that the learning actually sticks is a result of a myriad of design decisions, and many elements contribute to that likelihood. It will vary by learner, despite your endeavors, but you increase the probability that the desired outcome is achieved by following what’s know about how people learn.

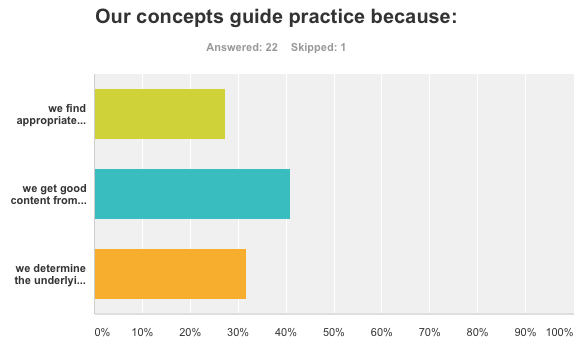

This is the point of learning engineering, applying learning science to the design of learning experiences. You need to align elements like:

- determining learning objectives that will impact the desired outcome

- designing sufficient contextualized practice

- appropriately presenting a conceptual model that guides performance

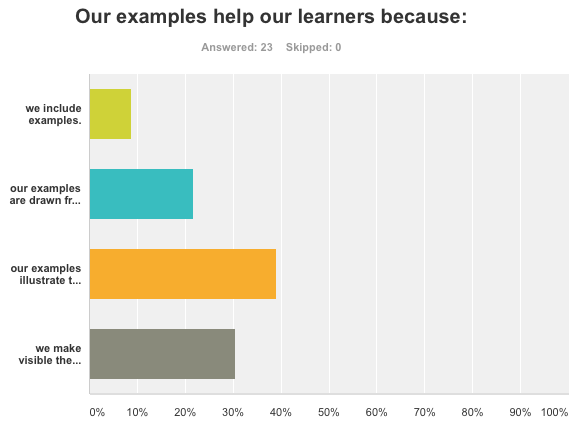

- providing a sufficient and elaborated suite of examples to illustrate the concept in context

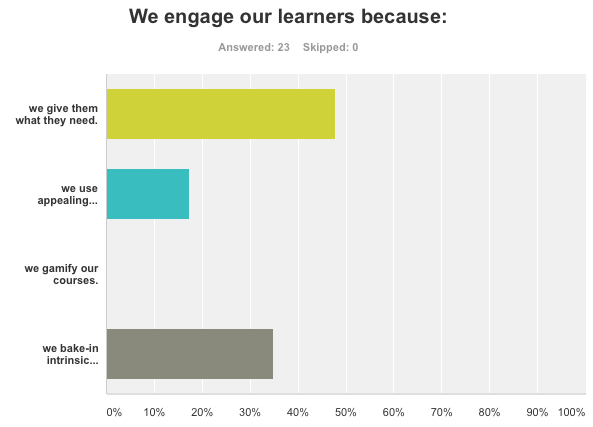

- developing emotional engagement

and so on.

And to the extent that you’re not fully delivering on the nuances of these elements, you’re decreasing the likelihood of having any meaningful impact. It’s pretty simple:

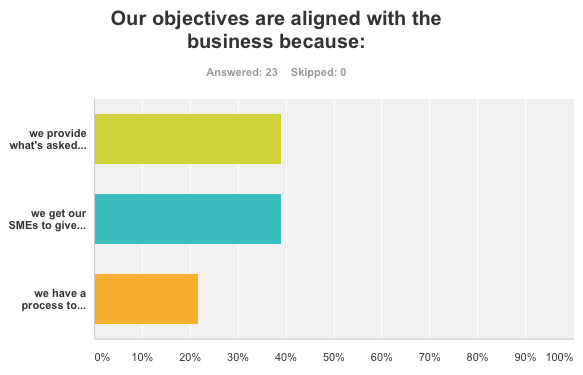

If you don’t have the right objectives (e.g. if you just take an order for a course), what’s the likelihood that your learning will achieve anything?

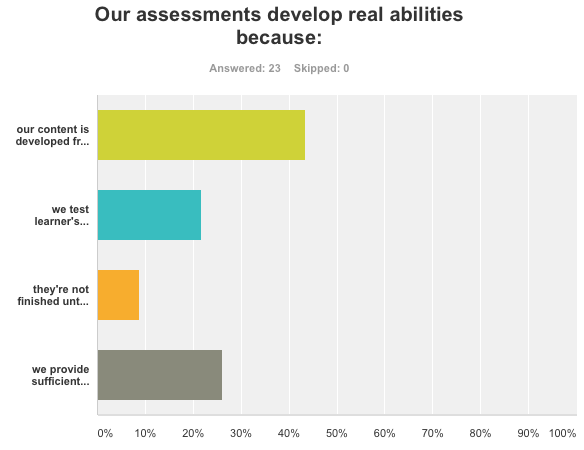

If you don’t have sufficient practice, what’s the likelihood that the learning will still be there when needed?

If you have abstract practice, what’s the likelihood that your learners will transfer that practice to appropriate situations?

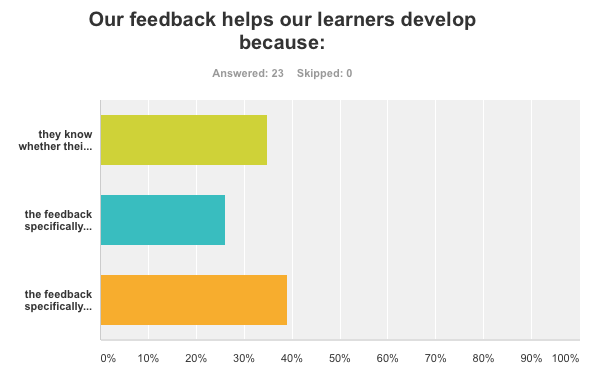

If you don’t guide performance with a model, what’s the likelihood that learners will be able to adapt their performance to different situations?

If you don’t provide examples, what’s the likelihood that learners will understand the full range of situations and appropriate adaptations for each?

And if you don’t emotionally engage them, what’s the likelihood that any of this will be appropriately processed?

Now, let’s tie that back to the dollars it costs you to develop this learning. There’s the SME time, and the designer time, and development time, and the time of the learners away from their revenue-generating activity. At the end of the day, it’s a fair chunk of change. And if you’re slipping in the details of any of this (and I’m just skating the surface, there’re nuances around all of these), you’re diminishing the value of your investment, potentially all the way to zero. In short, you could be throwing your money away!

This isn’t to make you throw up your hands and say “we can’t do all that”. Most design processes have the potential to do the necessary job, but you have to comprehend the nuances, and ensure that the i’s are dotted and t’s crossed on development. Just because you have an authoring tool doesn’t mean what comes out is actually achieving anything.

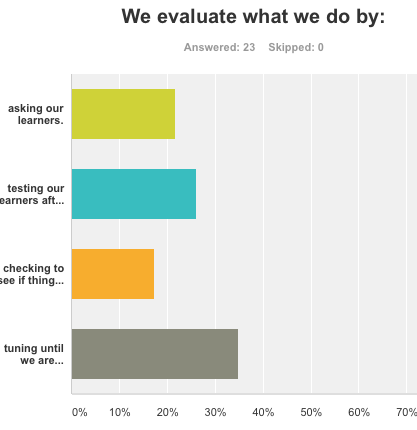

However, it’s possible to tune up the design process to acknowledge the necessary details. When you provide support at just the right places, and put in place the subtle tweaks on things like working with SMEs, you can develop and deliver learning that has a high likelihood of having the desired impact, and therefore have a process that’s justifiable for the investment.

And that’s really the goal, isn’t it? Being able to allocate resources to impact the business in meaningful ways is what we’re supposed to be doing. Too frequently we see the gaps continue (hence the call for Serious eLearning), and we can only do it if we’re acting like the professionals we need to be. It’s time for a tuneup in organizational learning. It’s not too onerous, and it’s needed. So, are you ready?