Bob Mosher opened the Performance Support Symposium with a passionate keynote about Performance Support. It strongly made the case for a blended approach, which I support. As with mobile, the time is definitely now.

Clark Quinn’s Learnings about Learning

by Clark 5 Comments

by Clark 3 Comments

It’s coming up to the 25th anniversary of HyperCard, and I’m reminded of how much that application played a role in my thinking and working at the time. Developed by Bill Atkinson, it was really ‘programming for the masses’, a tool for the Macintosh that allowed folks to easily build simple, and even complex, applications. I’d programmed in other environments : Algol, Pascal, Basic, Forth, and even a little Lisp, but this was a major step forward in simplicity and power.

A colleague of mine who was working at Claris suggested how cool this new tool was going to be, and I taught myself HyperCard while doing a postdoc at the University of Pittsburgh’s Learning Research and Development Center. I used it to prototype my ideas of a learning tool we could use for our research on children’s mental models of science. I then used it to program a game based upon my PhD research, embedding analogical reasoning puzzles into a game (Voodoo Adventure; see screenshot). I wrote it up and got it published as an investigation how games could be used as cognitive research tools. To little attention, back in ’91 :).

A colleague of mine who was working at Claris suggested how cool this new tool was going to be, and I taught myself HyperCard while doing a postdoc at the University of Pittsburgh’s Learning Research and Development Center. I used it to prototype my ideas of a learning tool we could use for our research on children’s mental models of science. I then used it to program a game based upon my PhD research, embedding analogical reasoning puzzles into a game (Voodoo Adventure; see screenshot). I wrote it up and got it published as an investigation how games could be used as cognitive research tools. To little attention, back in ’91 :).

While teaching HCI, I had my students use HyperCard to develop their interface solutions to my assignments. The intention was to allow them to focus more on design and less on syntax. I also reflected on how the interface encapsulated to some degree on what Andi diSessa called ‘incremental advantage’, a property of an environment that rewarded greater investments in understanding with greater power to control the system. HyperCard’s buttons, fields, and backgrounds provided this, up until the next step to HyperTalk (which also had that capability once you got into the programming notion). I also proposed that such an environment could support ‘discoverability’ (a concept I learned from Jean Marc Robert), where an environment could support experimentation to learn to use it in steady ways. Another paper resulted.

I also used HyperCard to develop applications in my research. We used it to develop Quest for Independence, a game that helped kids who grew up without parents (e.g. foster care) learn to survive on their own. Similarly, we developed a HCI performance support tool. Both of these later got ported to the web as soon as CGI’s came out that let the web retain state (you can still play Quest; as far as I know it was the first serious game you could play on the web).

The other ways HyperCard were used are well known (e.g. Myst), but it was a powerful tool for me personally, and I still miss having an easy environment for prototyping. I don’t program anymore (I add value other ways), but I still remember it fondly, and would love to have it running on my iPad as well! Kudos to Bill and Apple for creating and releasing it; a shame it was eventually killed through neglect.

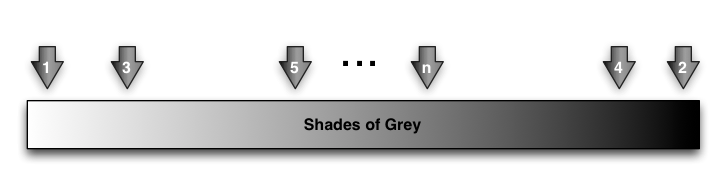

In looking across several instances of training in official procedures, I regularly see that, despite bunches of regulations and guidelines, that things are not black and white, but that there are myriad shades of grey. And I think that there is probably a very reasonable way to deal with it. (Surely you didn’t think I was talking about a book!)

In these situations, there are typically cases that are very white, others that are very black, but most end up somewhere in the middle, with a fair degree of ambiguity. And the concerns of the governing body are various. In one instance, the body was more concerned that you’d done due diligence and could show a trail of the thinking that led to the decision. If you did that, you were ok, even if you ended up making the wrong decision. In another case, the concern was more about consistency and repeatability. You didn’t want to show bias.

However, the training doesn’t really reflect that. In many cases, they point out the law (in the official verbiage), you work through some examples, and you’re quizzed on the knowledge. You might even workshop a few examples. Typically, you are to get the ‘right answer’.

I’d suggest that a better approach would be to give the learners a series of examples that are first workshopped by small groups, with their work brought back to the class. The important things are the ways the discussion is facilitated, supported, and the choice of problems. First, I think they’re given the problems and the associated requirements, guidelines, or regulations. Period. No presentation beforehand, nothing except reactivating the relevance of this material to their real work.

I’m suggesting that the first problem they face be, essentially, ‘white’, and the second is ‘black’ (or vice versa). The point is for them to see what the situation looks like when it’s very clear, and for them to get used to using the materials to make a determination. (This is likely what they’re going to be doing in real practice anyway!) At this point, the discussion facilitation is focused on helping them understand how the rules play out in the clear cases.

I’m suggesting that the first problem they face be, essentially, ‘white’, and the second is ‘black’ (or vice versa). The point is for them to see what the situation looks like when it’s very clear, and for them to get used to using the materials to make a determination. (This is likely what they’re going to be doing in real practice anyway!) At this point, the discussion facilitation is focused on helping them understand how the rules play out in the clear cases.

Then they start getting grayer cases, ones where there’s more ambiguity. Here, the focus of discussion facilitation is to start emphasizing the subtext: either ‘document your work’, or ‘be consistent’, or whatever. The amount of these will depend on how much practice they need. If the decisions are complex, they’re relatively infrequent, or the decisions are really important, they’ll need more practice.

This way, the learners are a) getting comfortable with the decisions, b) getting used to using the materials to make the decisions, and c) recognizing what’s really important.

I’m relatively certain that this may be problematic for some of the SMEs, who may prefer to argue for right/wrong answers, but I think it reflects the reality when you unpack the thinking behind the way it plays out in practice. And I think that’s more important for the learners, and the training organization, to recognize.

Of course, as they work in groups, the most valuable way to support them may be for them to have the coordinates of other members of their group to call on when they face really tough decisions. That sort of collaboration may trump formal instruction anyway ;).

First, I have to tout that my article on content systems has been published in Learning Solutions magazine. It complements my recent post on content and data.

Second, I’ll be presenting on mobile at the eLearning Guild’s Performance Support Symposium in September in Boston. Would welcome seeing you there. Also will be doing a deeper ID session for Mass. ISPI while I’m there.

Third, I’ll be keynoting the MobilearnAsia conference in Singapore at the end of October. It’s the first in the region, and if you’re in the neighborhood it should be a great way to get steeped in mobile.

Finally, I’ll be at the eLearning Guild’s DevLearn in November, presenting my mobile learning strategy workshop, among other things.

If you’re at one of these events, say “hi”!

by Clark 8 Comments

Of late, I’ve been both reviewing eLearning, and designing processes & templates. As I’ve said before, the nuances between well-designed and well produced eLearning are subtle, but important. Reading a forthcoming book that outlines the future but recounts the past, it occurs to me that it may be worthwhile to look at a continuum of possibilities.

For the sake of argument, let’s assume that the work is well-produced, and explore some levels of differentiation in quality of the learning design. So let’s talk about a lack of worthwhile objectives, lack of models, insufficient examples, insufficient practice, and lack of emotional connection. These combine into several levels of quality.

The first level is where there aren’t any, or aren’t good learning objectives. Here we’re talking about waffly objectives like ‘understand’, ‘know’, etc. Look, I’m not a behaviorist, but I think *when* you have formal learning goals (and that’s not as often as we deliver), you bloody well ought to have some pretty meaningful description around it. Instead what we see is the all-to-frequently observed knowledge dump and knowledge test.

Which, by the way, is a colossal waste of time and money. Seriously, you are, er, throwing away money if that’s your learning solution. Rote knowledge dump and test reliably lead to no meaningful behavior change. We even have a label for it in cognitive science: “inert knowledge”.

So let’s go beyond meaningless objectives, and say we are focused on outcomes that will make a difference. We’re ok from here, right? Er, no. Turns out there are several different ways we can go wrong. The first is to focus on rote procedures. You may want execution, but increasingly the situation is such that the decisions are too complex to trust a completely prescribed response. If it’s totally predictable, you automate it!

Otherwise, you have two options; you provide sufficient practice, as they do with airline plots and heart surgeons. If lives aren’t on the line and failure isn’t as expensive as training, you should focus on providing model-based instruction where you develop the performer’s understanding of what’s underlying the decisions of how to respond. That latter gives you a basis for reconstructing an appropriate response even if you forget the rote approach. I recommend this in general, of course.

Which brings up another way learning designs go wrong. Sufficient practice as mentioned above would suggest repeating until you can’t get it wrong. What we tend to see, however, is practice until you get it right. And that isn’t sufficient. Of course, I’m talking real practice, not knowledge test ala multiple choice questions. Learners need to perform!

We don’t see sufficient examples, either. While we don’t want to overwhelm our learners, we do need sufficient contexts to abstract across. And it does not have to occur in just one day, indeed, it shouldn’t! We need to space the learning out for anything more than the most trivial of learning. Yet the ‘event’ model of learning crammed into one session is much of what we see.

The final way many designs fails is to ignore the emotional side of the equation. This manifests itself in several ways, including introductions, examples, and practice. Too often, introductions let you know what you’re about to endure, without considering why you should care. If you’re not communicating the value to the learner, why should they care? I reckon that if you don’t convey the WIIFM, you better not expect any meaningful outcomes. There are more nuances here (e.g. activating relevant knowledge, etc), but this is the most egregious.

In examples and practice, too, the learner should see the relevance of what is being covered to what they know is important and they care about. These are two important and separate things. What they see should be real situations where the knowledge being addressed plays a real role. Then they should also care about the examples personally.

It’s hard to be able to address all the elements, but aligning them is critical to achieving well-designed, not just well-produced learning. Are you really making the necessary distinctions?

Really? Yes. Let me explain:

I’ve been reviewing some content for a government agency. This is exciting stuff, evaluating whether contract changes are valid. Ok, it’s not exciting to me, but to the audience it’s important. And there’s a reliable pattern to the slide deck that the instructor is supposed to use: it’s large amounts of text.

Again, exciting stuff, right from the regulations. But that’s important to this audience; I actually don’t have a problem with it. The problem is that it’s all crammed on one screen! Why is this a problem?

It’s not a problem for printing. You wouldn’t want to waste paper, and trees, printing it out. So being dense in this way isn’t bad. No, it’s bad when it’s presented.

When it’s presented, there is some highlighting of the important things. But if you were to hear someone go over the three wordy bullet points on one screen, you’d be hard pressed to follow. However, if you spaced the same screen out three times, one for each bullet point, , you’d support cognitive load more appropriately. You’re using more screens, but covering the same material in the same time, you’re just switching between screens emphasizing the separate points. And you don’t have to put each bullet point on a separate screen; to help maintain context you could have the same text but only the relevant one clear and the others greyed out or blurred.

Hey, screens are cheap. In fact, they’re essentially free! Using more screens when presenting doesn’t cost any more. Really! You can address each point clearly, maintaining context but helping focus attention. It’ll help the instructor too, not just the students.

Ok, so there is one cost. Maintaining a separate deck for printing and projecting could be some extra management overhead. But for one, who’s better at policies and procedures than the government? More seriously, I often will have a slide in my deck that’s a prose version of something I convey graphically, e.g. the five slides I use to present Brent Schlenker’s five-ables of social media (findable, feedable, linkable, taggable, editable). In the presentation I have a slide with an image for each. For print, I hide those five and show the one text one. It’s not that hard. The same principle could be used here, the full slide for printing, the three equivalents for presenting.

There are times when you want more slides. They’re simpler, more focused, and better support maintaining context and focus. Don’t scrimp on the slides. It’s better to have slides with not so much text, but if you must, space it out.

I just reviewed a paper submitted to a journal (one way to stay in touch with the latest developments), and all along they were doing research on the cognitive and motivational relationships in the game. They claimed it was a game, and proceeded on that assumption. And then the truth came out.

When designing and evaluating learning experiences, you really want to go beyond whether it’s effective or easy to use, and decide whether it’s engaging. Yes, you absolutely need to test usability first (if there’s a problem with the learning outcomes, is it the pedagogy or the interaction?), and then learning effectiveness. But ultimately, if you want it optimally tuned for success, pitched at the optimal learning level using meaningful activities, it should feel like a game. The business case is that the effectiveness will be optimized, and the tuning process to get there is less than you think (if you’re doing it right). And the only real way to test it is subjectively: do the players think it’s a game.

If you create a learning experience and call it game, but your learners don’t think it is, you undermine their motivation and your credibility. It can be relative (e.g. better than regular learning) as you might not have the resources to compete with commercial games, but it ought to be better than having to sit through a page turner, or you’ve failed.

There are systematic ways to design games that achieve both meaningful engagement and effective education practice. Heck, I wrote a whole book on the topic. It’s not magic, and while it requires tuning, it’s doable. And, as I’ve stated before: you can’t say it’s a game, only your players can tell you that.

So here were these folks doing research on a ‘game’. The punchline: “students, who started playing the game with high enthusiasm, started complaining after a short while, ‘this is not a game’, and stopped gameplay”. Fail.

Seriously, if you’re going to make a game, make it demonstrably fun. Or it’s not a game, whether you say so or not.

by Clark 2 Comments

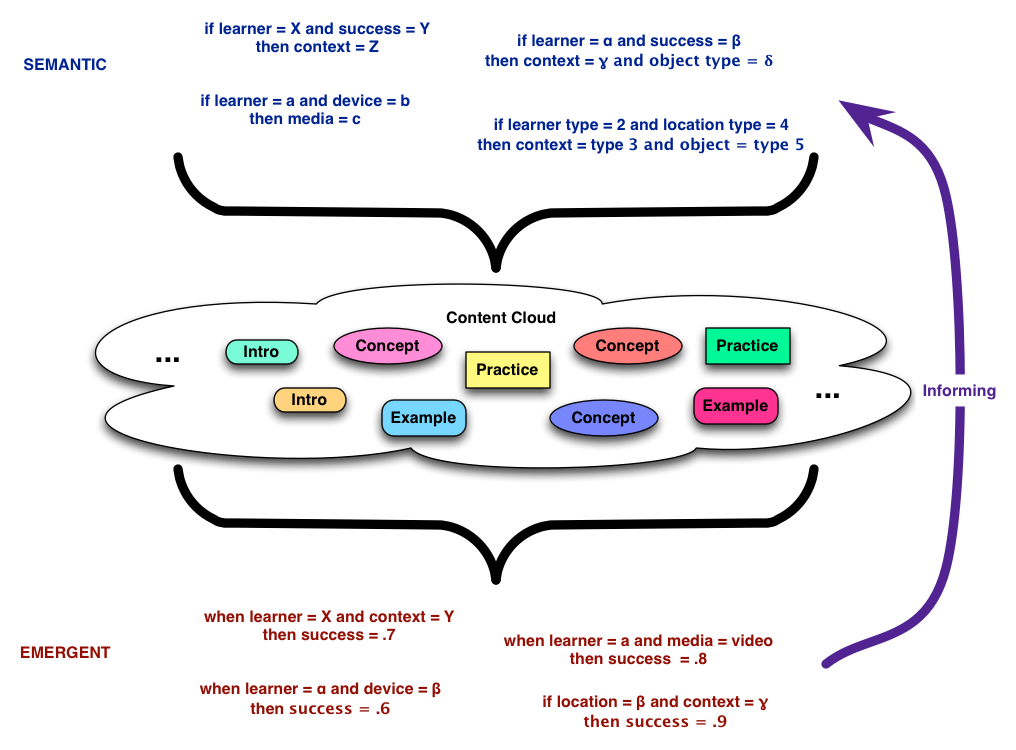

The last of the thoughts still percolating in my brain from #mlearncon finally emerged when I sat down to create a diagram to capture my thinking (one way I try to understand things is to write about them, but I also frequently diagram them to help me map the emerging conceptual relationships into spatial relationships).

What I was thinking about was how to distinguish between emergent opportunities for driving learning experiences, and semantic ones. When we built the Intellectricity© system, we had a batch of rules that guided how we were sequencing the content, based upon research on learning (rather than hardwiring paths, which is what we mostly do now). We didn’t prescribe, we recommended, so learners could choose something else, e.g. the next best, or browse to what they wanted. As a consequence, we also could have a machine learning component that would troll the outcomes, and improve the system over time.

What I was thinking about was how to distinguish between emergent opportunities for driving learning experiences, and semantic ones. When we built the Intellectricity© system, we had a batch of rules that guided how we were sequencing the content, based upon research on learning (rather than hardwiring paths, which is what we mostly do now). We didn’t prescribe, we recommended, so learners could choose something else, e.g. the next best, or browse to what they wanted. As a consequence, we also could have a machine learning component that would troll the outcomes, and improve the system over time.

And that’s the principle here, where mainstream systems are now capable of doing similar things. What you see here are semantic rules (made up ones), explicitly making recommendations, ideally grounded in what’s empirically demonstrated in research. In places where research doesn’t stipulate, you could also make principled recommendations based upon the best theory. These would recommend objects to be pulled from a pool or cloud of available content.

However, as you track outcomes, e.g. success on practice, and start looking at the results by doing data analytics, you can start trolling for emergent patterns (again, made up). Here we might find confirmation (or the converse!) of the empirical rules, as well as potentially new patterns that we may be able to label semantically, and even perhaps some that would be new. Which helps explain the growing interest in analytics. And, if you’re doing this across massive populations of learners, as is possible across institutions, or with really big organizations, you’re talking the ‘big data’ phenomena that will provide the necessary quantities to start generating lots of these outcomes.

Another possibility is to specifically set up situations where you randomly trial a couple alternatives that are known research questions, and use this data opportunity to conduct your experiments. This way we can advance our learning more quickly using our own hypotheses, while we look for emergent information as well.

Until the new patterns emerge, I recommend adapting on the basis of what we know, but simultaneously you should be trolling for opportunities to answer questions that emerge as you design, and look for emergent patterns as well. We have the capability (ok, so we had it over a decade ago, but now the capability is on tap in mainstream solutions, not just bespoke systems), so now we need the will. This is the benefit of thinking about content as systems – models and architectures – not just as unitary files. Are you ready?

by Clark 8 Comments

In a panel at #mlearncon, we were asked how instructional designers could accommodate mobile. Now, I believe that we really haven’t got our minds around a learning experience distributed across time, which our minds really require. I also think we still mistakenly think about performance support as separate from formal learning, but we don’t have a good way to integrate them.

I’ve advocated that we consider learning experience design, but increasingly I think we need performance experience design, where we look at the overall performance, and figure out what needs to be in the head, what needs to be in the world, and design them concurrently. That is, we look at what the person knows how to do, and what should be in their head, and what can be designed as support. ADDIE designs courses. HPT determines whether to do a job aid (the gap is knowledge), or training (the gap is a skill). I’m not convinced that either really looks at the total integration (and willing to be wrong).

What was triggered in my brain, however, was that social constructivism might be a framework within which we could accomplish this. By thinking of what activities the learners would be engaged in, and how we’d support that performance with resources and other learners and performers as collaborators when appropriate, we might have a framework. My take on social constructivism has it looking at what can and should be co-owned by the learner, and how to get the learner there, and it naturally involves resources, other people, and skill development.

So, you’d look at what needs to be done, and think through the performance, and ask what resources (digital and human) would be there with the performer, the gap between your current learner and the performer you’d need, and how to develop an experience to achieve that end state. The notion is what mental design process designers may need going forward, and what framework provides the overarching framework to support that design process.

It’s very related to my activity framework, which nicely resonates as it very much focuses on what you can do, and resourcing that, but that framework is focused on reframing education to make it skills focused and developing self learning. This would require some additions that I’ll have to ponder further. But, as always, it’s about getting ideas out there to collect feedback. So, what say you?

I had several great conversations over the course of last week’s #mLearnCon that triggered some interesting thoughts. Here’s the first:

I was talking with someone charged with important training: nuclear. We were talking about both the value of sims to support deep practice, and the difficulty in getting the necessary knowledge out of the subject matter expert (SME). These converged for me in what seemed an interesting way.

First, the best method to get the knowledge out of the heads of SMEs is Cognitive Task Analysis (CTA). CTA is highly effective, but also very complex. It requires considerable effort to do the official version.

A different thread was also wrapped up in this. Not surprisingly, I believe simulation games are the best form of deep practice to help cement skills. I believe so strongly I wrote a book about it ;).

And the cross-pollination: I believe that we’ll be passing on responsibility for defining curricular paths to competency in areas to the associated communities of practice. Further, I believe we will have collaboratively developed sims as part of that path, where we use wikis to edit the rules of the simulation to keep it up to date.

The integration in this context was to think of having the SMEs collaborate on the design of the sim as a way to make the necessary tacit knowledge explicit. It would make their understanding very concrete, and help ensure that the resulting sim is correct. Of course, they might rebel in terms of exaggerating and basing the practice in fantastic contexts, but it certainly would help focus on meaningful skills instead of rote knowledge.

The barrier is that experts don’t really have access to what they know, so having a concrete activity to ground their experience in practical ways strikes me as a very concrete way to elicit the necessary understandings. CTA is about detailed processes to get at their tacit knowledge, but perhaps sim design is a more efficient mechanism. It could have tradeoffs, but it seems to disintermediate the process.

OK, so it’s just a wild idea at this time, but I always argue that thinking out loud is valuable, and I try to practice what I preach. What think you?