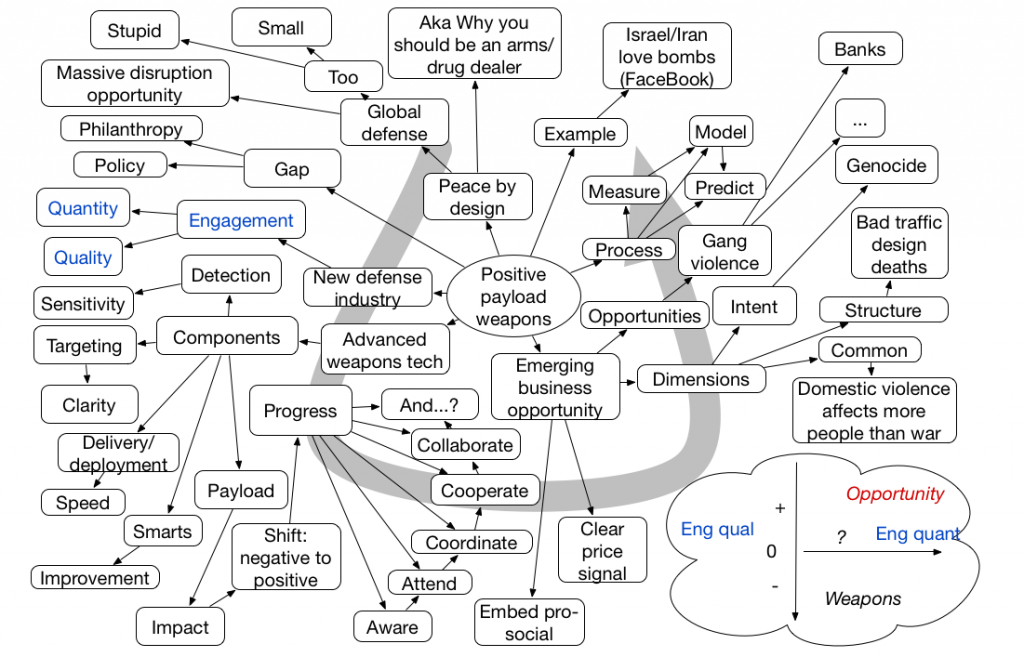

The other evening I went off to hear an intriguing sounding presentation on Positive Payload Weapons by Margarita Quihuis (who really just introduced the session) and Mark Nelson. As I sometimes do, I mind mapped it.

I have to say it’s an intriguing framework, but it appeared that they’ve not yet really put it into practice. In short, as the diagram in the lower right suggests, weapons have evolved to do more damage at greater range (from knives one on one to atomic bombs across the world). What could we do to evolve doing more good at greater range? From personal kudos to, well, that’s the open question. They cited the Israel-Iran Love Bombs as an example, and the tactical response.

Oh, yeah, the drug part is the serotonin you get from doing positive things (or something like that).

In a recent

In a recent