So, I’ve written about writing books, what makes a good book, and updated on mine (now a bit out of date). I thought it was maybe time to lay out their gestation and raison d’être. (I was also interviewed for a podcast, vidcast really, recently on the four newest, which brought back memories.) So here’re some brief thoughts on my books.

So, I’ve written about writing books, what makes a good book, and updated on mine (now a bit out of date). I thought it was maybe time to lay out their gestation and raison d’être. (I was also interviewed for a podcast, vidcast really, recently on the four newest, which brought back memories.) So here’re some brief thoughts on my books.

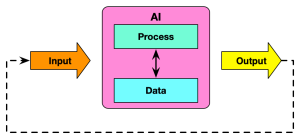

My first book, Engaging Learning came from the fact that a) I’d designed and developed a lot of learning games, and b) had been an academic and reflected and written on the principles and process. Thus, it made sense to write it. Plus, a) I was an independent and it seemed like a good idea, and b) the publisher wanted one (the time was right). In it, I laid out some principles for learning, engagement, and the intersection. Then I laid out a systematic process, and closed with some thoughts on the future. Like all my books, I tried to focus on the cognitive principles and not the technology (which was then and continues to change rapidly). It went out of print, but I got the rights back and have rereleased it (with a new cover) for cheap on Amazon.

I wanted to write what became my fourth book as the next screed. However, my publisher wanted a book on mobile (market timing). Basically, they said I could do the next one if I did this first. I had been involved in mlearning courtesy of Judy Brown and David Metcalfe, but I thought they should write it. Judy declined, and David reminded me that he had written one. Still I and my publisher thought there was room for a different perspective, and I wrote Designing mLearning. I recognized that the way we use mobile doesn’t mesh well with ‘courses on a phone’, and instead framed several categories of how we could use them. I reckon those categories are still relevant as ways to think about technology! Again, republished by me.

Before I could get to the next book, I was asked by one of their other brands if I could write a mobile book for higher education. The original promise was that it’d be just a rewrite of the previous, and we allocated a month. Hah! I did deliver a manuscript, but asked them not to publish it. We agreed to try again, and The Mobile Academy was the result. It looks at different ways mobile can augment university actions, with supporting the classroom as only one facet. This too was out of print but I’ve republished.

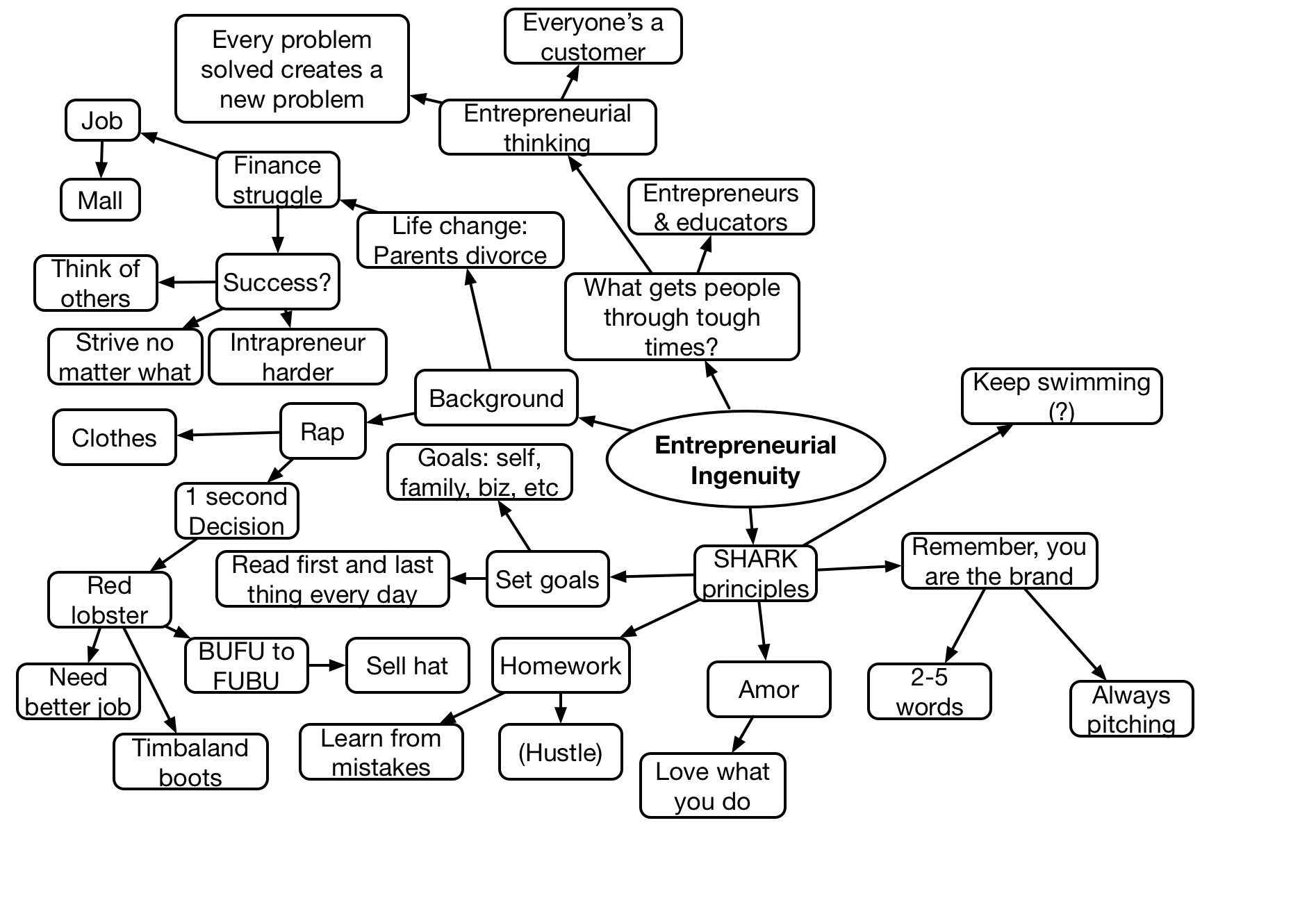

Finally, I could write the book I thought the industry needed, Revolutionize Learning & Development. Inspired by Marc Rosenberg’s Beyond eLearning and Jay Cross’s Informal Learning, this book synthesizes a performance and technology-enabled push for an ecosystem perspective. It may have been ahead of its time, but it’s still in print. More importantly, I believe it’s still relevant and even more pressing! Other books have complemented the message, but I still think it’s worth a read. Ok, so I’m biased, but I still hear good feedback ;). My editor suggested ATD as a co-publisher, and I was impressed with their work on marketing (long story).

Based upon the successes of those books (I like to believe), and an obvious need in our field, ATD asked for a book on the myths that plague our industry. Here I thought Will Thalheimer, having started the Debunkers Club, would be a better choice. He, however, declined, thinking it probably wasn’t a good business decision (which is likely true; not much call for keynotes or consulting on myths). So, I researched and wrote Millennials, Goldfish & Other Training Misconceptions. In it, I talked about 16 myths (disproved beliefs), 5 superstitions (things folks won’t admit to but emerge anyways) and 16 misconceptions (love/hate things). For each, I tried to lay out the appeal and the reality. I suggest what to do instead, for the bad practices. For the misconceptions, I try to identify when they make sense. In all cases I didn’t put down exhaustive references, but instead the most indicative. ATD did a great job with the book design, having an artist take my intro comic ideas for each and illustrating them, and making a memorable cover. (They even submitted it to a design competition, where it came close to winning!)

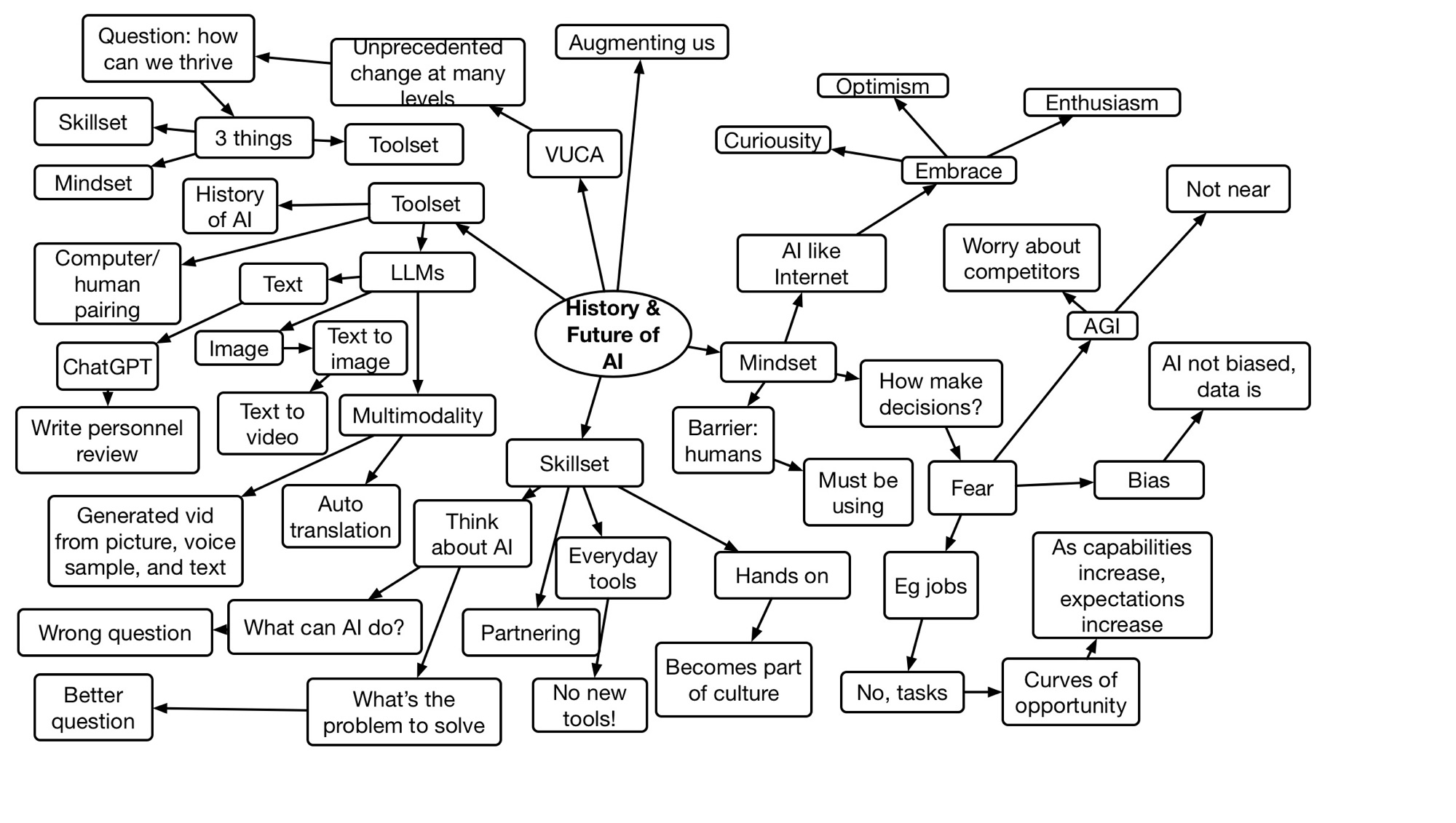

After the success of that tome, ATD came back and wanted a book on learning science. They’d previously asked me to edit the definitive tome, and while it was appealing, I didn’t want to herd cats. Despite their assurances, I declined. This, however, could be my own simple digest, so I agreed. Thus, Learning Science for Instructional Designers emerged. There are other books with different approaches that are good, but I do think I’ve managed to make salient the critical points from learning science that impact our designs. Frankly, I think it goes beyond instructional designers (really, parents, teachers, relatives, mentors and coaches, even yourself are designing instruction), but they convinced me to stick with the title.

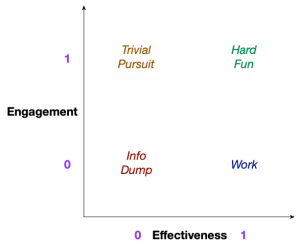

Now, I view Learning Experience Design as the elegant integration of learning science with engagement. My learning science book, along with others, does a good job of laying out the first part. But I felt that, other than game design books (including mine!), there wasn’t enough on the engagement side. So, I wanted a complement to that last book (though it can augment others). I wrote Make It Meaningful as that complement. In it, I resurrected the framework from my first book, but use it to go across learning design. (Really, games are just good practice, but there are other elements). I also updated my thinking since then, talking about both the initial hook and maintaining engagement through to the end. I present both principles and practical tips, and talk about the impact on your standard learning elements. In an addition I think is important, I also talk about how to take your usual design process, and incorporate the necessary steps to create experiences, not just instruction. I do want you to create transformational experiences!

So, that’s where I’m at. You can see my recommended readings here (which likely needs an update.) Some times people ask “what’s your next book”, and my true answer at this point is “I don’t know.” Suggestions? Something that I’m qualified to write about, that there’s not already enough out about, and it’s a pressing need? I welcome your thoughts!