I was on LinkedIn, and noted this list of influences in a profile: “complex systems, cybernetics, anthropology, sociology, neuroscience, (evolutionary) biology, information technology and human performance.” And, to me, that’s a redundancy. Why?

I was on LinkedIn, and noted this list of influences in a profile: “complex systems, cybernetics, anthropology, sociology, neuroscience, (evolutionary) biology, information technology and human performance.” And, to me, that’s a redundancy. Why?

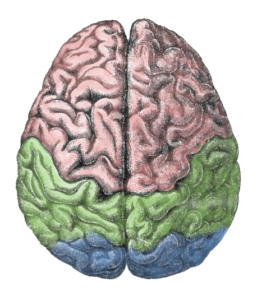

A while ago, I said “Departments of cognitive science tend to include psychologists, linguists, sociologists, anthropologists, philosophers, and, yes, neuroscientists. ” I missed artificial intelligence and computer science more generally. Really, it’s about everything that has to do with human thought, alone, or in aggregate. In a ‘post-cognitive’ era, we also recognize that thinking is not just in the head, but external. And it’s not just the formal reasoning, or lack thereof, but it’s personality (affect), and motivation (conation).

Cognitive science emerged as a way to bring different folks together who were thinking about thinking. Thus, that list above is, to me, all about cognitive science! And I get why folks might want to claim that they’re being integrative, but I’m saying “been there, done that”. Not me personally, to be clear, but rather that there’s a field doing precisely that. (Though I have pursued investigations across all of the above in my febrile pursuit of all things about applied cognitive science.)

Why should we care? Because we need to understand what’s been empirically shown about our thinking. If we want to develop solutions – individual, organizational, and societal – to the pressing problems we face, we ought to do so in ways that are most aligned with how our brains work. To do otherwise is to invite inefficiencies, biases, and other maladaptive practices.

Part of being evidence-informed, in my mind, is doing things in ways that align with us. And there is lots of room for improvement. Which is why I love learning & development, these are the people who’ve got the most background, and opportunity, to work on these fronts. Yes, we need to liase with user experience, and organizational development, and more, but we are (or should be) the ones who know most about learning, which in many ways is the key to thinking (about thinking).

So, I’ve argued before that maybe we need a Chief Cognitive Officer (or equivalent). That’s not Human Resources, by the way (which seems to be a misnomer along the lines of Human Capital). Instead, it’s aligning work to be most effective across all the org elements. Maybe now more than ever before! At least, that’s where my thinking keeps ending up. Yours?