I’ve long maintained that our organizational practices are too often misaligned with how our brains really work. I’ve attributed that to a legacy from previous eras. Yet, I realize that there may be another legacy, a cognitive one. Here I’ll suggest we need to move beyond Industrial Age thinking.

I’ve long maintained that our organizational practices are too often misaligned with how our brains really work. I’ve attributed that to a legacy from previous eras. Yet, I realize that there may be another legacy, a cognitive one. Here I’ll suggest we need to move beyond Industrial Age thinking.

The premise comes from business. We transitioned from a largely agricultural economy to a manufacturing economy, of goods and services. Factories got economic advantage from scale. We also essentially treated people as parts of the machine. Taylorism, aka scientific management, looked at how much a person could produce if they were working as efficiently as possible, without damage. So few were educated, and we didn’t have sufficiently sophisticated mechanisms. Times change, and we’re now in an information age. Yet, a number of our approaches are still based upon industrial approaches. We’re living on a legacy.

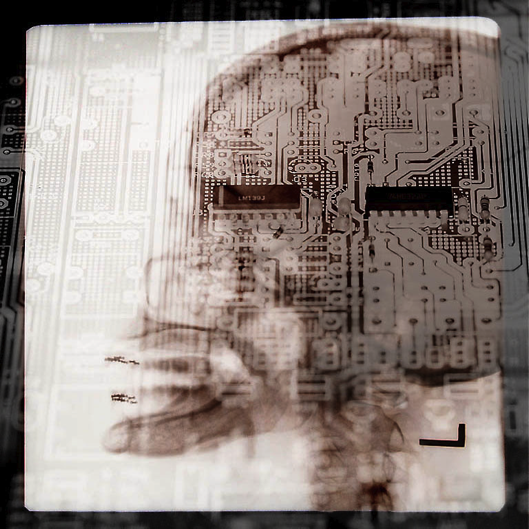

Now I’m taking this is to our models of mind. The cognitive approach is certainly more recent than the Industrial Age, but it carries its own legacies. We regularly take technology as metaphors for mind. Before the digital computer, for instance, telephone switching was briefly used as a model. The advent of the digital computer, a general purpose information system, is a natural next step. We’re information processing machines, so aren’t we like computers?

It turns out, we’re not. There’s considerable evidence that we are not formal, logical, reasoning machines. In fact, we do well what it’s hard to get computers to do, and vice-versa. We struggle to remember large quantities of data, or abstract and arbitrary information, and to remember it verbatim. Yet we also are good at pattern-matching and meaning-making (sometimes too good; *cough* conspiracy theories *cough*). Computers are the opposite. They can remember large quantities of information accurately, but struggle to do meaning-making.

My concern is that we’re still carrying a legacy of formal reasoning. That is, the notion that we can do it all in our heads, alone, continues though it’s been proven inaccurate. We make inferences and take actions based upon this assumption, perhaps not even consciously!

How else to explain, for instance, the continuing prevalence of information presentation under the guise of training? I suggest there’s a lingering belief that if we present information to people, they’ll logically change their behavior to accommodate. Information dump and knowledge test are a natural consequence of this perspective. Yet, this doesn’t lead to learning!

When we look at how we really perform, we recognize that we’re contextually-influenced, and tied to previous experience. If we want to do things differently, we have to practice doing it differently. We can provide information (specifically mental models, examples, and feedback) to facilitate both initial acquisition and continual improvement, but we can’t just present information.

If we want to truly apply learning science to the design of instruction, we have to understand our brains. In reality, not outdated metaphors. That’s the opportunity, and truly the necessity. We need to move beyond Industrial Age thinking, and incorporate post-cognitive perspectives. To the extent we do, we stand to benefit.

Just wanted to confirm… do you feel the information processing model is still relevant?

Curtis, yes, and…it’s a start. There’re some interesting new results that are emergent and an addition to this picture. Situated, distributed, and embodied cognition all add nuances, as does emotion and predictive coding, but also all can be extended from this initial foundation.

Thanks! very interesting reflection