I’ve talked in the past about mental models (and continue to do so), but they seem a difficult concept to grasp. I was discussing them again in preparation for this post by partner Elevator 9. Despite their utility, grounding in fundamental cognition, and value in learning, they continue to be absent or misunderstood in our learning interventions. It’s worth taking some time and modeling mental models in use.

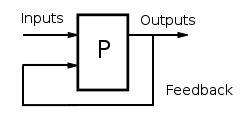

To start with, what are mental models? Wikipedia defines them as “an internal representation of external reality”. Really, it’s an explanation of how a small part of the world works. Wikipedia goes on to add “the mind constructs ‘small-scale models’ of reality that it uses to anticipate events”. They can manifest as equations, or sets of rules, but really, to me, they’re constructed from causal conceptual relationships. That is, there are entities, connected by causality. For example, feedback loops are a mental model. They occur in many situations, and what happens is that something takes the output, and feeds it back to the input, positively or negatively, to influence subsequent actions. For instance, a thermostat uses the temperature as a way to determine whether to turn on or off a heater or cooling device.

To start with, what are mental models? Wikipedia defines them as “an internal representation of external reality”. Really, it’s an explanation of how a small part of the world works. Wikipedia goes on to add “the mind constructs ‘small-scale models’ of reality that it uses to anticipate events”. They can manifest as equations, or sets of rules, but really, to me, they’re constructed from causal conceptual relationships. That is, there are entities, connected by causality. For example, feedback loops are a mental model. They occur in many situations, and what happens is that something takes the output, and feeds it back to the input, positively or negatively, to influence subsequent actions. For instance, a thermostat uses the temperature as a way to determine whether to turn on or off a heater or cooling device.

The next question is why mental models. Back to Wikipedia: they “can help shape behaviour and set an approach to solving problems”. To me, they’re explanatory and predictive, in that they can explain why something occurred, and predict the outcome of various actions. It’s that latter that provides the instructional value. We want people to make good decisions. If they have a basis for determining the outcome of different courses of action, they can choose the best one. Providing them with a model for the domain, e.g. interpersonal relations (c.f. situational leadership), gives learners a way to choose optimally.

There’s evidence that our brains will build models, and that they won’t necessarily be good ones. In addition, if we don’t have a good model, we try to patch it rather than replace it. Which isn’t necessarily effective. Thus, the best approach is to provide a good model up front, and demonstrate its use. Then we use examples to demonstrate models in context, showing how the abstract concepts map to real world elements. Further, in general, we provide them before we give practice in most cases.

Instructionally, then, providing models is good support for making decisions. I’ve argued before that making decisions is more likely to be the deciding value for organizations (as opposed to fact recall). Thus, instruction around making better decisions is important. Therefore, instruction using models is going to be valuable! As a relevant aside, in many cases they’re valuably communicated via diagrams or, in the case where dynamics are important for comprehension, via animation. The point is that as they’re conceptual, you save the photos or videos for the examples.

Finally, if models are useful, then they should be part of our instructional toolkit. One small problem is that subject matter experts have compiled their knowledge away, and may not have conscious access to the mental models they use. This makes it difficult to extract them and make them comprehensible to novices. Yet, clearly, they’re useful, so we should be doing that. Knowing what they are and why they’re useful is, hopefully, a motivator for making the effort. And, succeeding!

So, please, spend the effort. We should be modeling mental models to our learners. Find, refine, and present the models via examples. Then develop them through practice, and use them in feedback, explicitly. With models, we have a better basis for learning design, and better chances for successful improvement. Which is what it’s about, right?

Note: I talk about mental models in my book Learning Science for Instructional Designers.

Leave a Reply