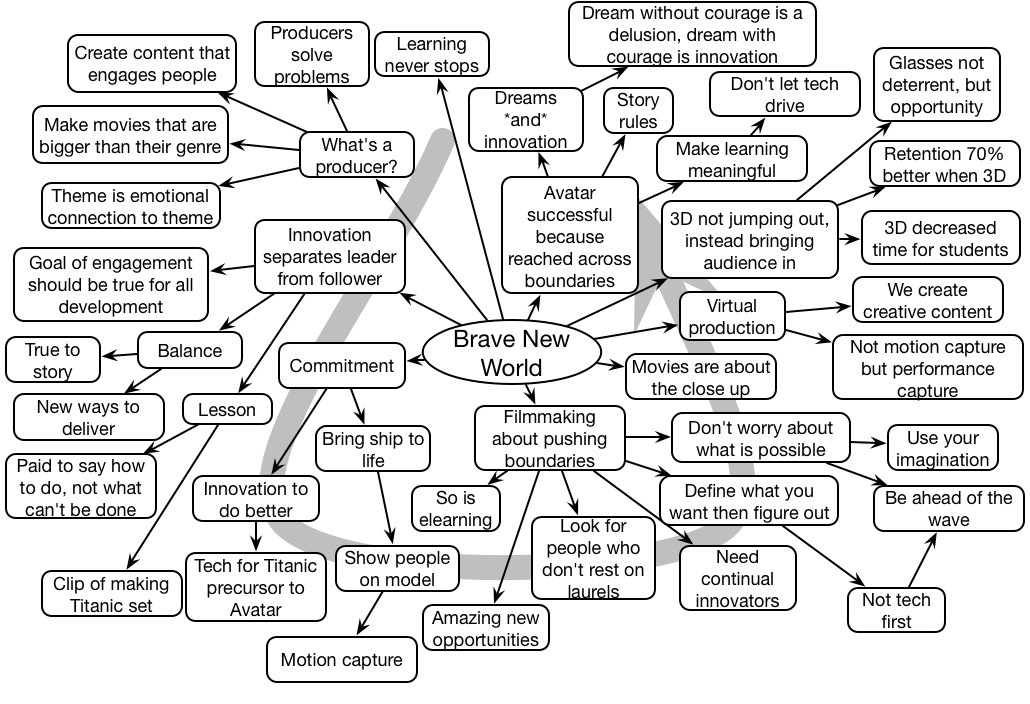

At the recent DevLearn, several of us gathered together in a Junto to talk about issues we felt were becoming important for our field. After a mobile learning panel I realized that, just as mlearning makes it too easy to think about ‘courses on a phone’, I worry that ‘learning experience design’ (a term I’ve championed) may keep us focused on courses rather than exploring the full range of options including performance support and eCommunity.

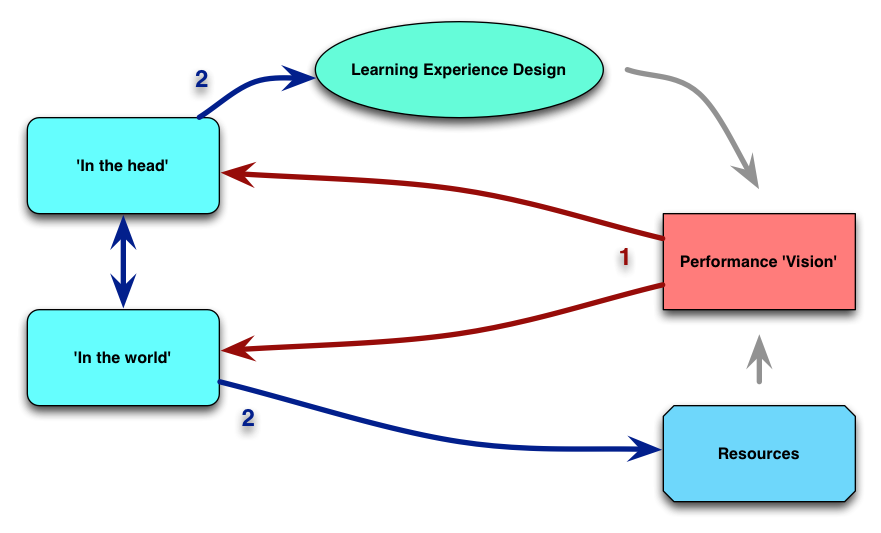

So I began thinking about performance experience design as a way to keep us focused on designing solutions to performance needs in the organization. It’s not just about what’s in our heads, but as we realize that our brains are good at certain things and not others, we need to think about a distributed cognition solution, looking at how resources can be ‘in the world’ as well as in others’ heads.

The next morning in the shower (a great place for thinking :), it occurred to me that what is needed is a design process before we start designing the solution. To complement Kahnemann’s Thinking Fast and Slow (an inspiration for my thoughts on designing for how we really think and learn), I thought of designing backward and forward. Let me try to make that concrete.

What I’m talking about is starting with a vision of what performance would look like in an ideal world, working backward to what can be in the world, and what needs to be in the head. We want to minimize the latter. I want to respect our humanity in a way, allowing us to (choose to) do the things we do well, and letting technology take on the things we don’t want to do.

What I’m talking about is starting with a vision of what performance would look like in an ideal world, working backward to what can be in the world, and what needs to be in the head. We want to minimize the latter. I want to respect our humanity in a way, allowing us to (choose to) do the things we do well, and letting technology take on the things we don’t want to do.

In my mind, the focus should be on what decisions learners should be making at this point, not what rote things we’re expecting them to do. If it’s rote, we’re liable to be bad at it. Give us checklists, or automate it!

From there, we can design forward to create those resources, or make them accessible (e.g. if they’re people). And we can design the ‘in the head’ experience as well, and now’s the time for learning experience design, with a focus on developing our ability to make those decisions, and where to find the resources when we need them. The goal is to end up designing a full performance solution where we think about the humans in context, not as merely a thinking box.

It naturally includes design that still reflects my view about activity-centered learning (which I’m increasingly convinced is grounded in cognitive research). Engaging emotion, distributed across platforms and time, using a richer suite of tools than just content delivery and tests. And it will require using something like Michael Allen’s Successive Approximation Model perhaps, recognizing the need to iterate.

I wanted to term this performance experience design, and then as several members workshopped this with me, I thought we should just call it performance design (at least externally, to stakeholders not in our field, we can call it performance experience design for ourselves). And we can talk about learning experience design within this, as well as information design, and social networks, and…

It’s really not much more than what HPT would involve, e.g. the prior consideration of what the problem is, but it’s very focused on reducing what’s in the head, including emotion in the learning when it’s developed, using social resources as well as performance support, etc. I think this has the opportunity to help us focus more broadly in our solution space, make us more relevant to the organization, and scaffold us past many of our typical limitations in approach. What do you think?