Dave Cormier made an eloquent case for rhizomatic learning.

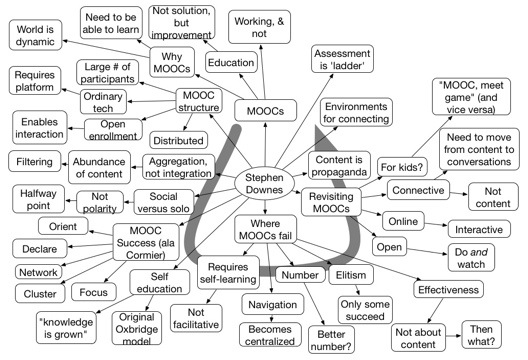

Stephen Downes #EDGEX2012 Mindmap

Reimagining Learning

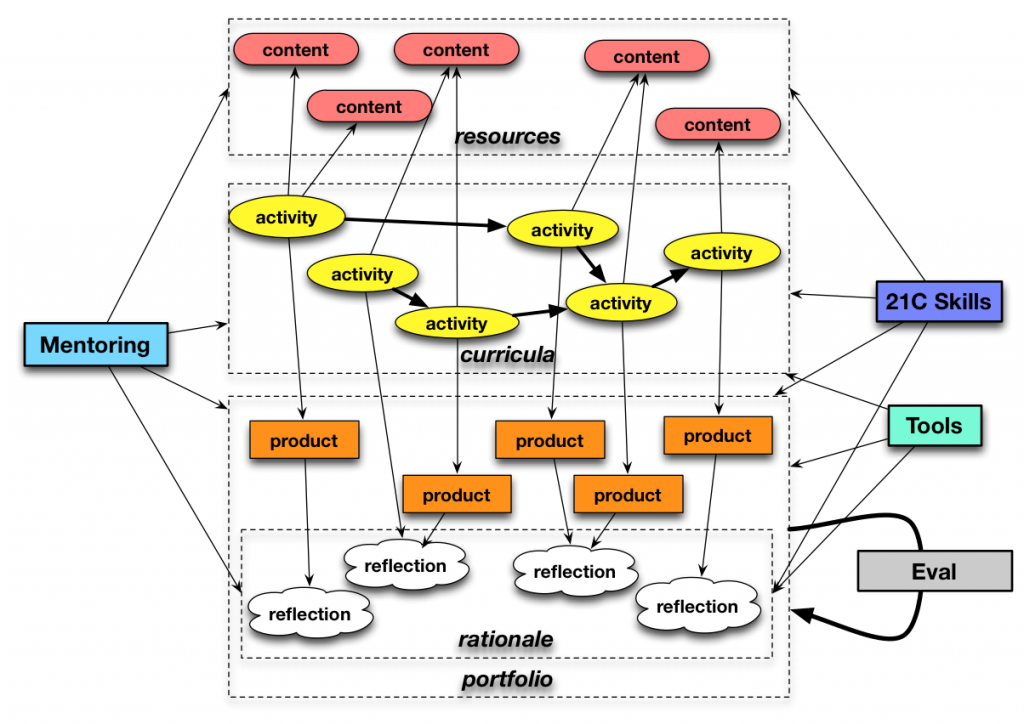

On the way to the recent Up To All Of Us unconference (#utaou), I hadn’t planned a personal agenda. However, I was going through the diagrams that I’d created on my iPad, and discovered one that I’d frankly forgotten. Which was nice, because it allowed me to review it with fresh eyes, and it resonated. And I decided to put it out at the event to get feedback. Let me talk you through it, because I welcome your feedback too.

Up front, let me state at least part of the motivation. I’m trying to capture rethinking about education or formal learning. I’m tired of anything that allows folks to think knowledge dump and test is going to lead to meaningful change. I’m also trying to ‘think out loud’ for myself. And start getting more concrete about learning experience design.

Let me start with the second row from the top. I want to start thinking about a learning experience as a series of activities, not a progression of content. These can be a rich suite of things: engagement with a simulation, a group project, a museum visit, an interview, anything you might choose for an individual to engage in to further their learning. And, yes, it can include traditional things: e.g. read this chapter.

Let me start with the second row from the top. I want to start thinking about a learning experience as a series of activities, not a progression of content. These can be a rich suite of things: engagement with a simulation, a group project, a museum visit, an interview, anything you might choose for an individual to engage in to further their learning. And, yes, it can include traditional things: e.g. read this chapter.

This, by the way, has a direct relation to Project Tin Can, a proposal to supersede SCORM, allowing a greater variety of activities: Actor – Verb – Object, or I – did – this. (For all I can recall, the origin of the diagram may have been an attempt to place Tin Can in a broad context!)

Around these activities, there are a couple of things. For one, content is accessed on the basis of the activities, not the other way around. Also, the activities produce products, and also reflections.

For the activities to be maximally valuable, they should produce output. A sim use could produce a track of the learner’s exploration. A group project could provide a documented solution, or a concept-expression video or performance. An interview could produce an audio recording. These products are portfolio items, going forward, and assessable items. The assessment could be self, peer, or mentor.

However, in the context of ‘make your thinking visible’ (aka ‘show your work’), there should also be reflections or cognitive annotations. The underlying thinking needs to be visible for inspection. This is also part of your portfolio, and assessable. This is where, however, the opportunity to really recognize where the learner is, or is not, getting the content, and detect opportunities for assistance.

The learner is driven to content resources (audios, videos, documents, etc) by meaningful activity. This in opposition to the notion that content dump happens before meaningful action. However, prior activities can ensure that learners are prepared to engage in the new activities.

The content could be pre-chosen, or the learners could be scaffolded in choosing appropriate materials. The latter is an opportunity for meta-learning. Similarly, the choice of product could be determined, or up to learner/group choice, and again an opportunity for learning cross-project skills. Helping learners create useful reflections is valuable (I recall guiding honours students to take credit for the work they’d done; they were blind to much of the own hard work they had put in!).

When I presented this to the groups, there were several questions asked via post-its on the picture I hand-drew. Let me address them here:

What scale are you thinking about?

This unpacks. What goes into activity design is a whole separate area. And learning experience design may well play a role beneath this level. However, the granularity of the activities is at issue. I think about this at several scales, from an individual lesson plan to a full curriculum. The choice of evaluation should be competency-based, assessed by rubrics, even jointly designed ones. There is a lot of depth that is linked to this.

How does this differ from a traditional performance-based learning model?

I hadn’t heard of performance-based learning. Looking it up, there seems considerable overlap. Also with outcome-based learning, problem-based learning, or service learning, and similarly Understanding By Design. It may not be more, I haven’t yet done the side-by-side. It’s scaling it up , and arguably a different lens, and maybe more, or not. Still, I’m trying to carry it to more places, and help provide ways to think anew about instruction and formal education.

An interesting aside, for me, is that this does segue to informal learning. That is, you, as an adult, choose certain activities to continue to develop your ability in certain areas. Taking this framework provides a reference for learners to take control of their own learning, and develop their ability to be better learners. Or so I would think, if done right. Imagine the right side of the diagram moving from mentor to learner control.

How much is algorithmic?

That really depends. Let me answer that in conjunction with this other comment:

Make a convert of this type of process out of a non-tech traditional process and tell that story…

I can’t do that now, but one of the attendees suggested this sounded a lot like what she did in traditional design education. The point is that this framework is independent of technology. You could be assigning studio and classroom and community projects, and getting back write-ups, performances, and more. No digital tech involved.

There are definite ways in which technology can assist: providing tools for content search, and product and reflection generation, but this is not about technology. You could be algorithmic in choosing from a suite of activities by a set of rules governing recommendations based upon learner performance, content available, etc. You could also be algorithmic in programming some feedback around tech-traversal. But that’s definitely not where I’m going right now.

Similarly, I’m going to answer two other questions together:

How can I look at the path others take? and How can I see how I am doing?

The portfolio is really the answer. You should be getting feedback on your products, and seeing others’ feedback (within limits). This is definitely not intended to be individual, but instead hopefully it could be in a group, or at least some of the activities would be (e.g. communing on blog posts, participating in a discussion forum, etc). In a tech-mediated environment, you could see others’ (anonymized) paths, access your feedback, and see traces of other’s trajectories.

The real question is: is this formulation useful? Does it give you a new and useful way of thinking about designing learning, and supporting learning?

MOOC reflections

A recent phenomena is the MOOC, Massively Open Online Courses. I see two major manifestations: the type I have participated in briefly (mea culpa) as run by George Siemens, Stephen Downes, and co-conspirators, and the type being run by places like Stanford. Each share running large numbers of students, and laudable goals. Each also has flaws, in my mind, which illustrate some issues about education.

The Stanford model, as I understand it (and I haven’t taken one), features a rigorous curriculum of content and assessments, in technical fields like AI and programming. The goal is to ensure a high quality learning experience to anyone with sufficient technical ability and access to the Internet. Currently, the experience does support a discussion board, but otherwise the experience is, effectively, solo.

The connectivist MOOCs, on the other hand, are highly social. The learning comes from content presented by a lecturer, and then dialog via social media, where the contributions of the participants are shared. Assessment comes from participation and reflection, without explicit contextualized practice.

The downside of the latter is just that, with little direction, the courses really require effective self-learners. These courses assume that through the process, learners will develop learning skills, and the philosophical underpinning is that learning is about making the connections oneself. As was pointed out by Lisa Chamberlin and Tracy Parish in an article, this can be problematic. As of yet, I don’t think that effective self-learning skills is a safe assumption (and we do need to remedy).

The problem with the former is that learners are largely dependent on the instructors, and will end up with that understanding, that learners aren’t seeing how other learners conceptualize the information and consequently developing a richer understanding. You have to have really high quality materials, and highly targeted assessments. The success will live and die on the quality of the assessments, until the social aspect is engaged.

I was recently chided that the learning theories I subscribe to are somewhat dated, and guilty as charged; my grounding has taken a small hit by my not being solidly in the academic community of late. On the other hand, I have yet to see a theory that is as usefully integrative of cognitive and social learning theory as Cognitive Apprenticeship (and willing to be wrong), so I will continue to use (my somewhat adulterated version of) it until I am otherwise informed.

From the Cognitive Apprenticeship perspective, learners need motivating and meaningful tasks around which to organize their collective learning. I reckon more social interaction will be wrapped around the Stanford environment, and that either I’ve not experienced the formal version of the connectivist MOOCs, or learners will be expected to take on the responsibility to make it meaningful but will be scaffolded in that (if not already).

The upshot is that these are valuable initiatives from both pragmatic and principled perspectives, deepening our understanding while broadening educational reach. I look forward to seeing further developments.

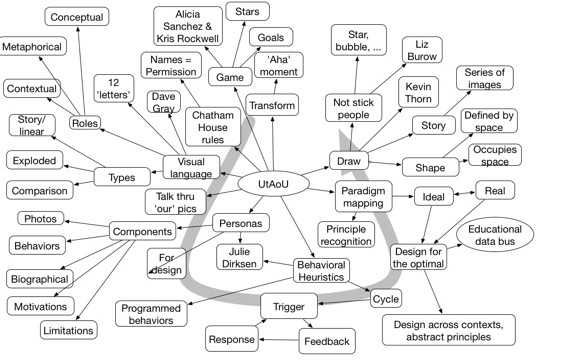

UTAOU Sunday mindmap

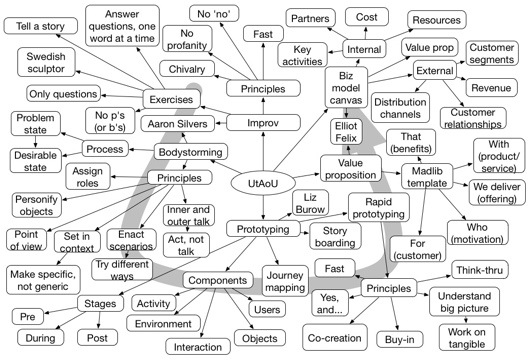

UTAOU Saturday Mindmap

Designing the killer experience

I haven’t been put in the place of having ultimate responsibility for driving a complete user experience for over a decade, though I’ve been involved in advising on a lot on many such. But I continue my decades long fascination with design, to the extent that it’s a whole category for my posts! An article on how Apple’s iPhone was designed caused me to reflect.

On one such project, I asked early on: “who owns the vision?” The answer soon became clear that no one had complete ownership. Their model was having a large-scope goal, and then various product managers take pieces of that, and negotiated for budget, with vendors for resources, and with other team members for the capability to implement their features. And this has been a successful approach for many internet businesses, project managers owning their parts.

I compare that to the time I led a team, a decade ago developing a learning system, and I laid out and justified a vision, gave them each parts, and while they took responsibility for their part of the interlocking responsibilities, I was responsible for the overall experience.

Which is not to say by any means was I as visionary as Steve Jobs. In the article, he apparently told his iPhone team to start from a premise “to create the first phone that people would fall in love with”. I like to think that I was working towards that, but I clearly hadn’t taken ownership of such a comprehensive vision, though we were working towards one in our team.

And we were a team. Everyone could offer opinions, and the project was better because of it. I did my best to make it safe for everyone’s voice to be heard. We met together weekly, I had everyone backing up someone else’s area of responsibility, and they worked together as much as they worked with me. In many ways, my role was to protect them from bureaucracy just as my boss’ role was to protect me from interference. And it worked: we got a working prototype up and running before the bubble burst.

(I remember one time, the AI architect and the software engineer came in asking me to resolve an issue. At the end of it I didn’t fully understand the issue, yet they profoundly thanked me even though we all three knew I hadn’t contributed anything but the space for them to articulate their two viewpoints. They left having found a resolution that I didn’t have to understand.)

And I don’t really don’t know what the answer is, but my inclination is that giving folks a vibrant goal and asking them to work together to make it so, rather than giving individuals tasks that can compete to succeed. I can see the virtues of Darwinian selection, but I have to believe, based upon things like Dan Pink’s Drive and my work with my colleagues in the Internet Time Alliance, that giving a team a noble goal, resourcing them, and giving them the freedom to pursue it, is going to lead to a greater outcome. So, what do you think?

Reviewing elearning examples

I recently wrote about elearning garbage, and in case I doubted my assessment, today’s task made my dilemma quite clear. I was asked to be one of the judges for an elearning contest. Seven courses were identified as ‘finalists’, and my task was to review each and assign points in several categories. Only one was worthy of release, and only one other even made a passing grade. This is a problem.

Let me get the good news out of the way first. The winner, (in my mind; the overall findings haven’t been tabulated yet) did a good job of immediately placing the learner in a context with a meaningful task. It was very compelling stuff, with very real examples, and meaningful decisions. The real world resources were to be used to accomplish the task (I cheated; I did it just by the information in the scenarios), and mistakes were guided towards the correct answer. There was enough variety in the situations faced to cover the real range of possibilities. If I were to start putting this information into practice in the real world, it might stick around.

On the other hand, there were the six other projects. When I look at my notes, there were some common problems. Not every problem showed up in every one, but all were seen again and again. Importantly, it could easily be argued that several were appropriately instructionally designed, in that they had clear objectives, and presented information and assessment on that information. Yet they were still unlikely to achieve any meaningfully different abilities. There’s more to instructional design than stipulating objectives and then knowledge dump with immediate test against those objectives.

The first problem is that most of them were information objectives. There was no clear focus on doing anything meaningful, but instead the ability to ‘know’ something. And while in some cases the learner might be able to pass the test (either because they can keep trying ’til they get it right, or the alternatives to the right answer were mind-numbingly dumb; both leading to meaningless assessment), this information wasn’t going to stick. So we’ve really got two initial problems here, bad objectives and bad assessment..

In too many cases, also, there was no context for the information; no reason how it connected to the real world. It was “here’s this information”. And, of course, one pass over a fairly large quantity with some unreasonable and unrealistic expectation that it would stick. Again, two problems: lack of context and lack of chunking. And, of course, tests for random factoids that there was no particular reason to remember.

But wait, there’s more! In no case was there a conceptual model to tie the information to. Instead of an organizing framework, information was presented as essentially random collections. Not a good basis for any ability to regenerate the information. It’s as if they didn’t really care if the information actually stuck around after the learning experience.

Then, a myriad of individual little problems: bad audio in two, dull and dry writing pretty much across the board, even timing that of course meant you were either waiting on the program, or it was not waiting on you. The graphics were largely amateurish.

And these were finalists! Some with important outcomes. We can’t let this continue, as people are frankly throwing money on the ground. This is a big indictment of our field, as it continues to be widespread. What will it take?

Will tablets diverge?

After my post trying to characterize the differences between tablets and mobile, Amit Garg similarly posted that tablets are different. He concludes that “a conscious decision should be made when designing tablet learning (t-learning) solutions”, and goes further to suggest that converting elearning or mlearning directly may not make the most sense. I agree.

As I’ve suggested, I think the tablet’s not the same as a mobile phone. It’s not always with you, and consequently it’s not ready for any use. A real mobile device is useful for quick information bursts, not sustained attention to the device. (I’ll suggest that listening to audio, whether canned or a conversation, isn’t quite the same, the mobile device is a vehicle, not the main source of interaction.) Tablets are for more sustained interactions, in general. While they can be used for quick interactions, the screen size supports more sustained interactions.

So when do you use tablets? I believe they’re valuable for regular elearning, certainly. While you would want to design for the touch screen interface rather than mimic a mouse-driven interaction. Of course, I believe you also should not replicate the standard garbage elearning, and take advantage of rethinking the learning experience, as Barbara Means suggested in the SRI report for the US Department of Education, finding that eLearning was now superior to F2F. It’s not because of the medium itself, but because of the chance to redesign the learning.

So I think that tablets like the iPad will be great elearning platforms. Unless the task is inherently desktop, the intimacy of the touchscreen experience is likely to be superior. (Though more than Apple’s new market move, the books can be stunning, but they’re not a full learning experience.) But that’s not all.

Desktops, and even laptops don’t have the portability of a tablet. I, and others, find that tablets are taken more places than laptops. Consequently, they’re available for use as performance support in more contexts than laptops (and not as many as smart or app phones). I think there’ll be a continuum of performance support opportunities, and constraints like quantity of information (I’d rather look at a diagram on a tablet) constraints of time & space in the performance context, as well as preexisting pressures for pods (smartphone or PDA) versus tablets will determine the solution.

I do think there will be times when you can design performance support to run on both pads and pods, and times you can design elearning for both laptop and tablet (and tools will make that easier), but you’ll want to do a performance context analysis as well as your other analyses to determine what makes sense.

Stop creating, selling, and buying garbage!

I was thinking today (on my plod around the neighborhood) about how come we’re still seeing so much garbage elearning (and frankly, I had a stronger term in mind). And it occurred to me that their are multitudinous explanations, but it’s got to stop.

One of the causes is unenlightened designers. There are lots of them, for lots of reasons: trainers converted, lack of degree, old-style instruction, myths, templates, the list goes on. You know, it’s not like one dreams of being an instructional designer as a kid. This is not to touch on their commitment, but even if they did have courses, they’d likely still not be exposed to much about the emotional side, for instance. Good learning design is not something you pick up in a one week course, sadly. There are heuristics (Cat Moore’s Action mapping, Julie Dirksen’s new book), but the necessary understanding of the importance of the learning design isn’t understood and valued. And the pressures they face are overwhelming if they did try to change things.

Because their organizations largely view learning as a commodity. It’s seen as a nice to have, not as critical to the business. It’s about keeping the cost down, instead of looking at the value of improving the organization. I hear tell of managers telling the learning unit “just do that thing you do” to avoid a conversation about actually looking at whether a course is the right solution, when they do try! They don’t know how to hire the talent they really need, it’s thin on the ground, and given it’s a commodity, they’re unlikely to be willing to really develop the necessary competencies (even if they knew what they are).

The vendors don’t help. They’ve optimized to develop courses cost-effectively, since that’s what the market wants. When they try to do what really works, they can’t compete on cost with those who are selling nice looking content, with mindless learning design. They’re in a commodity market, which means that they have to be efficiency oriented. Few can stake out the ground on learning outcomes, other than an Allen Interactions perhaps (and they’re considered ‘expensive’).

The tools are similarly focused on optimizing the efficiency of translating PDFs and Powerpoints into content with a quiz. It’s tarted up, but there’s little guidance for quality. When it is, it’s old school: you must have a Bloom’s objective, and you must match the assessment to the objective. That’s fine as far as it goes, but who’s pushing the objectives to line up with business goals? Who’s supporting aligning the story with the learner? That’s the designer’s job, but they’re not equipped. And tarted up quiz show templates aren’t the answer.

Finally, the folks buying the learning are equally complicit. Again, they don’t know the important distinctions, so they’re told it’s soundly instructionally designed, and it looks professional, and they buy the cheapest that meets the criteria. But so much is coming from broken objectives, rote understanding of design, and other ways it can go off the rails, that most of it is a waste of money.

Frankly, the whole design part is commoditized. If you’re competing on the basis of hourly cost to design, you’re missing the point. Design is critical, and the differences between effective learning and clicky-clicky-bling-bling are subtle. Everyone gets paying for technology development, but not the learning design. And it’s wrong. Look, Apple’s products are fantastic technologically, but they get the premium placing by the quality of the experience, and that’s coming from the design. It’s the experience and outcome that matters, yet no one’s investing in learning on this basis.

It’s all understandable of course (sort of like the situation with our schools), but it’s not tolerable. The costs are high:meaningless jobs, money spent for no impact, it’s just a waste. And that’s just for courses; how about the times the analysis isn’t done that might indicate some other approach? Courses cure all ills, right?

I’m not sure what the solution is, other than calling it out, and trying to get a discussion going about what really matters, and how to raise the game. Frankly, the great examples are all too few. As I’ve already pointed out in a previously referred post, the awards really aren’t discriminatory. I think folks like the eLearning Guild are doing a good job with their DevLearn showcase, but it’s finger-in-the-dike stuff.

Ok, I’m on a tear, and usually I’m a genial malcontent. But maybe it’s time to take off the diplomatic gloves, and start calling out garbage when we see it. I’m open to other ideas, but I reckon it’s time to do something.