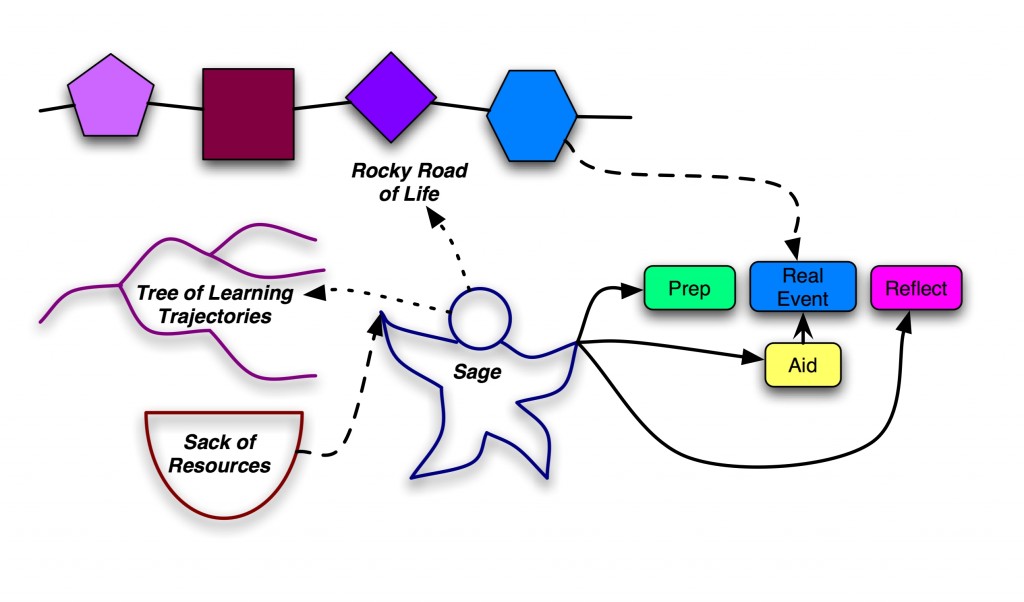

I’ve been using the tag ‘learning experience design strategy’ as a way to think about not taking the same old approaches of events über ales. The fact of the matter is that we’ve quite a lot of models and resources to draw upon, and we need to rethink what we’re doing.

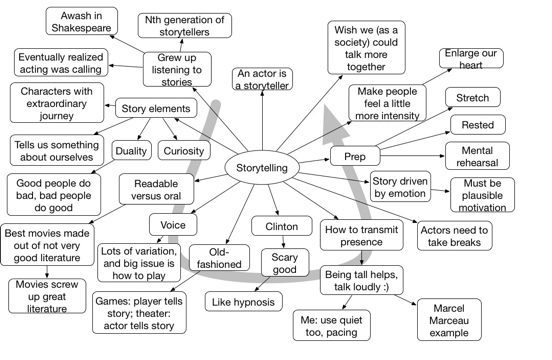

The problem is that it goes far beyond just a more enlightened instructional design, which of course we need. We need to think of content architectures, blends between formal and informal, contextual awareness, cross-platform delivery, and more. It involves technology systems, design processes, organizational change, and more. We also need to focus on the bigger picture.

Yet the vision driving this is, to me, truly inspiring: augmenting our performance in the moment and developing us over time in a seamless way, not in an idiosyncratic and unaligned way. And it is strategic, but I’m wondering if architecture doesn’t better capture the need for systems and processes as well as revised design.

This got triggered by an exercise I’m engaging in, thinking how to convey this. It’s something along the lines of:

The curriculum’s wrong:

- it’s not knowledge objectives, it’s skills

- it’s not current needs, it’s adapting to change

- it’s not about being smart, it’s about being wise

The pedagogy’s wrong:

- it’s not a flood, but a drip

- it’s not knowledge dump, it’s decision-making

- it’s not expert-mandated, instead it’s learner-engaging

- it’s not ‘away from work’, it’s in context

The performance model is wrong:

- it’s not all in the head, it’s distributed across tools and systems.

- it’s not all facts and skill, it’s motivation and confidence

- it’s not independent, it’s socially developed

- it’s not about doing things right, it’s about doing the right thing

The evaluation is wrong:

- it’s not seat time, it’s business outcomes

- it’s not efficiency, at least until it’s effective

- it’s not about normative-reference, it’s about criteria

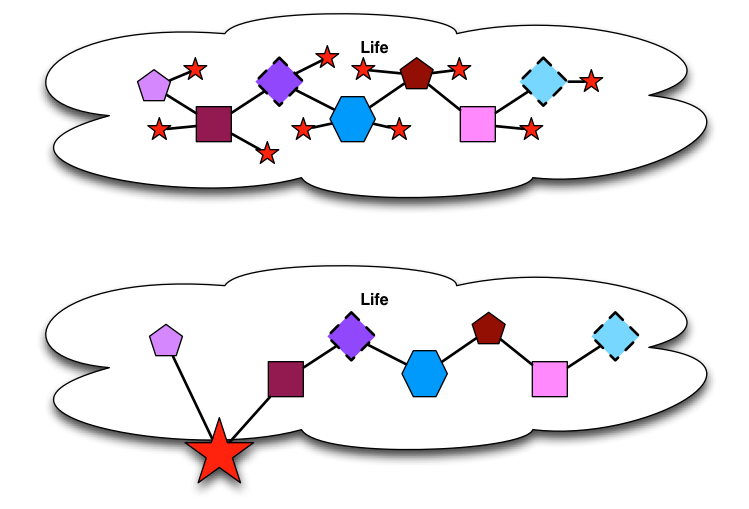

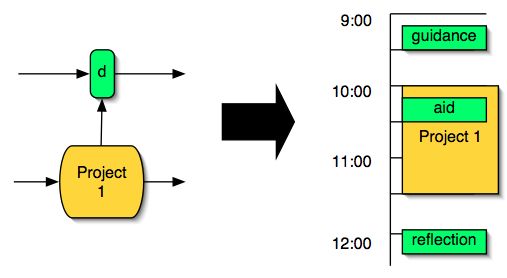

So what does this look like in practice? I think it’s about a support system organized so that it recognizes what you’re trying to do, and provides possible help. On top of that, it’s about showing where the advice comes from, developing understanding as an additional light layer. Finally, on top of that, it’s about making performance visible and looking at the performance across the previous level, facilitating learning to learn. And, the underlying values are also made clear.

It doesn’t have to get all that right away. It can start with just better formal learning design, and a bit of content granularity. It certainly starts with social media involvement. And adapting the culture in the org to start developing meta-learning. But you want to have a vision of where you’re going.

And what does it take to get here? It needs a new design that starts from the performance gap and looks at root causes. The design process then onsiders what sort of experience would both achieve the end goal and the gaps in the performer equation (including both technology aids and knowledge and skill upgrades), and consider how that develops over time recognizing the capabilities of both humans and technology, with a value set that emphasis letting humans do the interesting work. It’ll also take models of content, users, context, and goals, with a content architecture and a flexible delivery model with rich pictures of what a learning experience might look like and what learning resources could be. And an implementation process that is agile, iterative, and reflective, with contextualized evaluation. At least, that sounds right to me.

Now, what sounds right to you: learning experience design strategy, performance system design, performance architecture, <your choice here>?