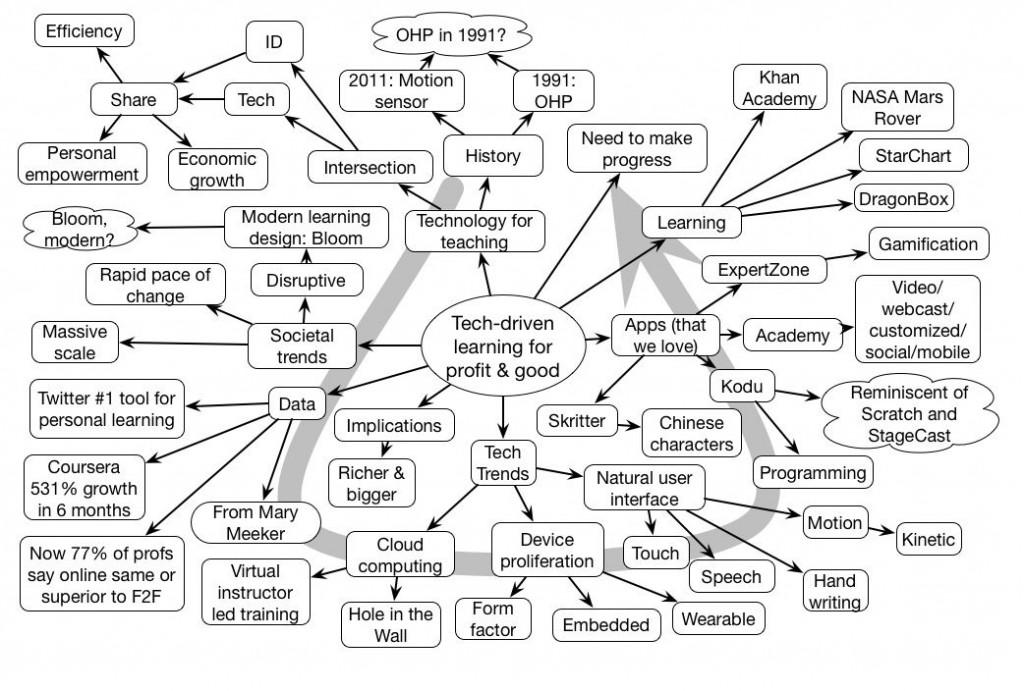

Christopher Pirie opened the eLearning Guild’s mLearnCon mobile learning conference with a fair overview of technology for learning. He talked about the usual trends, and pointed to some interesting game apps for learning. Kodu, in particular, is an interesting advancement on things like Scratch and StageCast’s Creator.

I was somewhat surprised by his pointer to Bloom as the turning point to modern learning design, as I’d be inclined to point more to Collins & Brown’s Cognitive Apprenticeship. I also think he should take a look at Donald Clark’s criticisms of Mitra’s Hole in the Wall. Finally, the characterization between the overhead projector as characteristic of 1991 and the Kinect for 2012 is a bit spurious: in 1991 we also had HyperCard, and in 2012 I don’t see the Kinect in many classrooms yet, but his point is apt about the potential for change we have at our fingertips.

Overall, a nice kickoff for the conference.