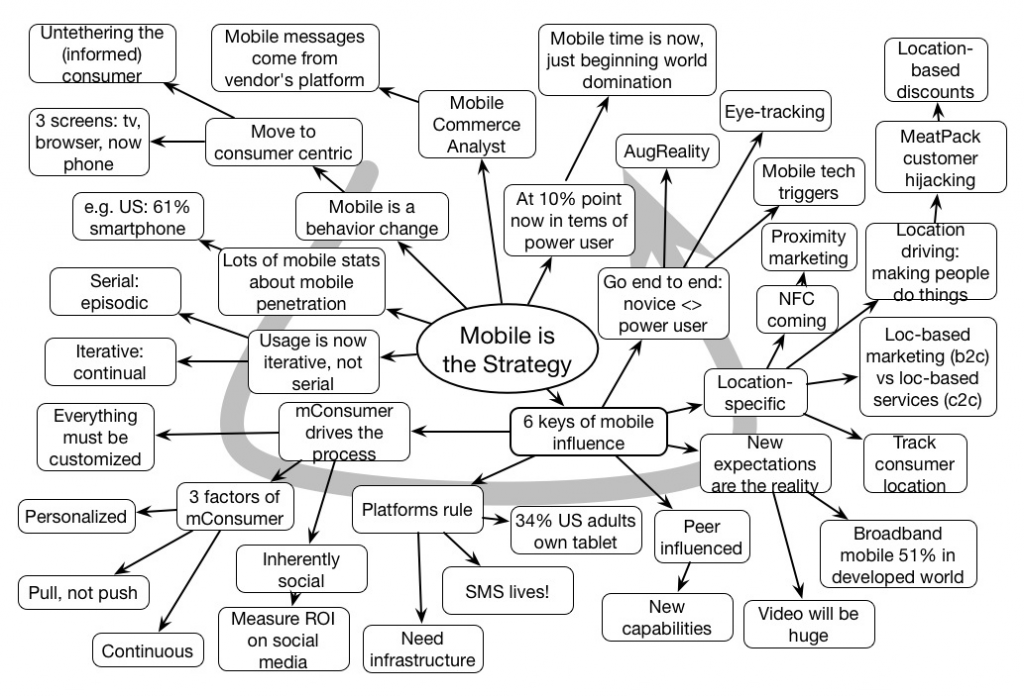

Chuck Martin gave a lively and valuable keynote at #mLearnCon, with stats on mobile growth, and then his key components of what he thinks will be driving mobile. He illustrated his points with funny and somewhat scary videos of how companies are taking advantage of mobile.

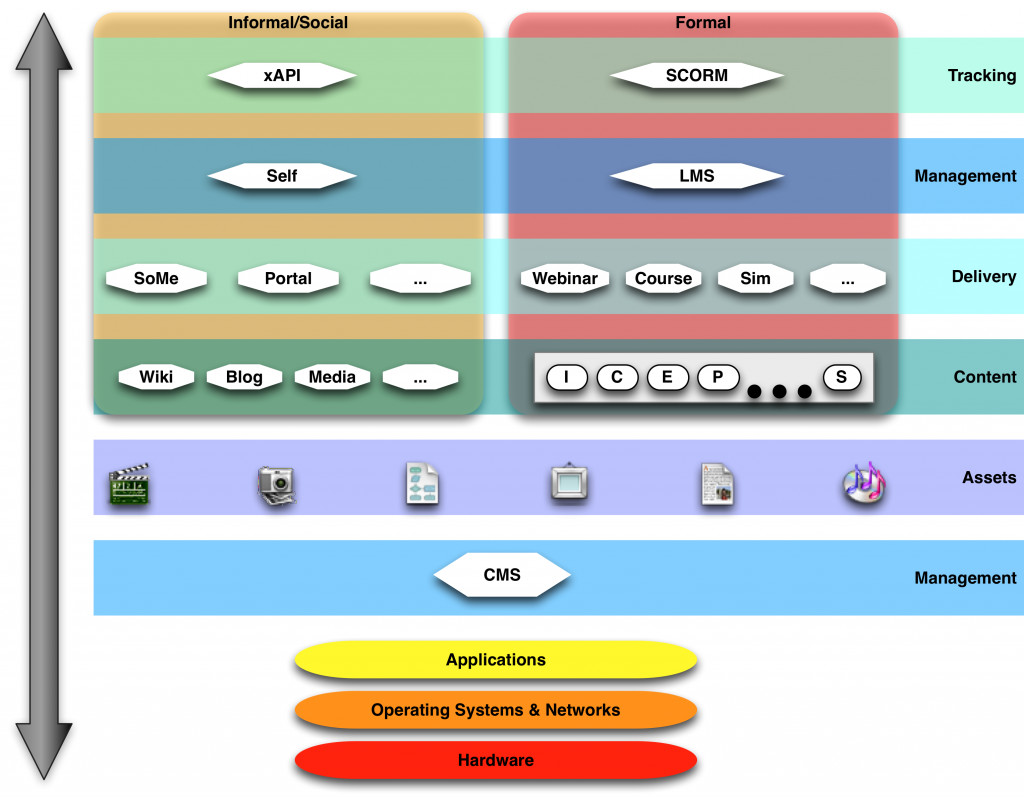

Technology Architecture

A few years ago, I created a diagram to capture a bit about the technology to support learning (Big ‘L’ Learning). I was revisiting that diagram for some writing I’m doing, and thought it needed updating. The point is to characterize the relationship between underpinning infrastructure and mechanisms to support availability for formal and informal learning.

Here’s the accompanying description: As a reference framework, we can think of a hierarchy of levels of tools. At the bottom is the hardware, running an operating system and connecting to networks. Above that are applications that deliver core services. We start with the content management systems, from the delivery perspective, which maintains media assets. Above that we have the aggregation of those assets into content, whether full learning consisting of introductions, concepts, examples, practice items, all the way to the summary, or user-generated content via a variety of tools. These are served up via delivery channels and managed, whether through webinars, courses, or simulations through a learning management system (LMS) on the formal learning side, or self-managed through social media and portals on the informal learning side. Ultimately, these activities can or will be tracked through standards such as SCORM for formal learning or the new experience API (xAPI) for informal learning.

Here’s the accompanying description: As a reference framework, we can think of a hierarchy of levels of tools. At the bottom is the hardware, running an operating system and connecting to networks. Above that are applications that deliver core services. We start with the content management systems, from the delivery perspective, which maintains media assets. Above that we have the aggregation of those assets into content, whether full learning consisting of introductions, concepts, examples, practice items, all the way to the summary, or user-generated content via a variety of tools. These are served up via delivery channels and managed, whether through webinars, courses, or simulations through a learning management system (LMS) on the formal learning side, or self-managed through social media and portals on the informal learning side. Ultimately, these activities can or will be tracked through standards such as SCORM for formal learning or the new experience API (xAPI) for informal learning.

I add, as a caveat: Note that this is merely indicative, and there are other approaches possible. For instance, this doesn‘t represent authoring tools for aggregating media assets into content. Similarly, individual implementations may not have differing choices, such as not utilizing an independent content management system underpinning the media asset and content development.

So, my question to you is, does this make sense? Does this diagram capture the technology infrastructure for learning you are familiar with?

No Folk Science-Based Design!

When we have to act in the world, make decisions, there are a lot of bases we use. Often wrongly. And we need to call it out and move on.

As I pointed out before, Kahneman tells us how we often make decisions on less than expert reflection, more so when we’re tired, and create stories about why we do it. If we’re not experts, we shouldn’t trust our ‘gut’, but we do. And we will use received wisdom, rightly or wrongly, to justify our choices. Yet sometimes the beliefs we have about how things work are wrong.

While there’s a lot of folk science around that’s detrimental to society and more, I want to focus on folk science that undermines our ability to assist people in achieving their goals, supporting learning and performance. Frankly, there are a lot of persistent myths that are used to justify design decisions that are just wrong. Dr. Will Thalheimer, for instance, has soundly disabused Dale’s Cone. Yet the claims continue. There’re more: learning styles, digital natives, I could go on. They are not sound bases for learning design!

It goes on: much of what poses under ‘brain-based’ learning, that any interaction is good, that high production values equal deep design, that knowledge dump and test equals learning. Folks, if you don’t know, don’t believe it. You have to do better!

Sure, some of it’s compelling. Yes, learners do differ. That doesn’t mean a) that there are valid instruments to assess those differences, or more importantly b) that you should teach them differently. Use the best learning principles, regardless! And using the year someone’s born to characterize them really is pretty coarse; it almost seems like discrimination.

Look, intuition is fine in lieu of any better alternative, but when it comes to designing solutions that your organization depends on, doing anything less than science-based design is frankly fraudulent. It’s time for evidence-based design!

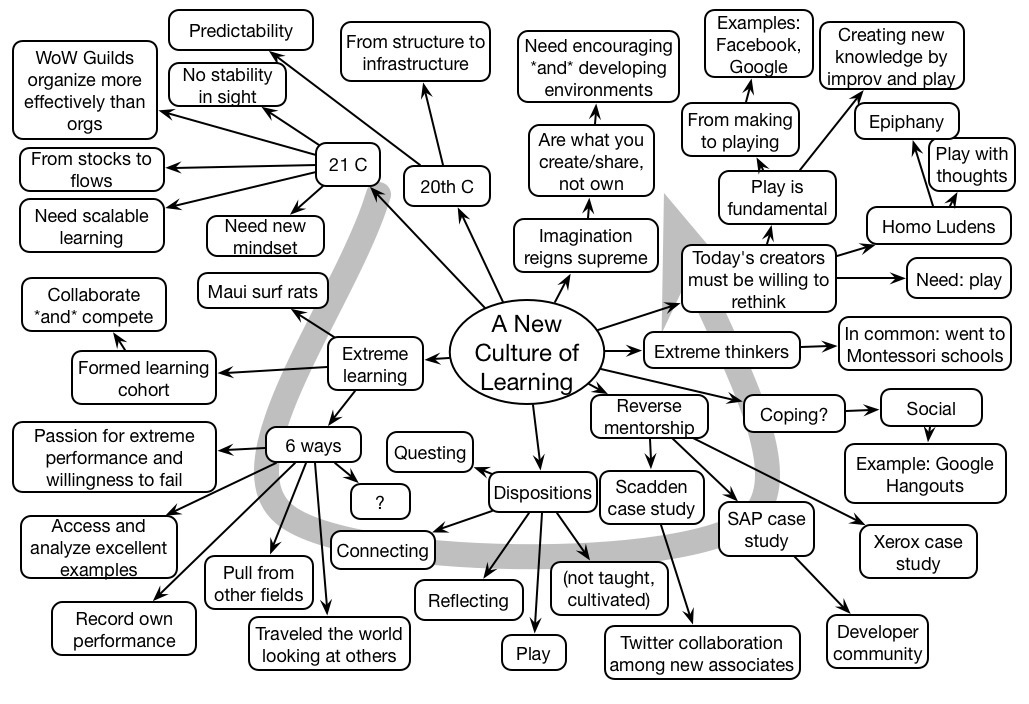

JSB #astd2013 Keynote Mindmap

Starting Strategy

If you’re going to move towards the performance ecosystem, a technology-enabled workplace, where do you start? Partly it depends on where you’re at, as well as where you’re going, but it also likely depends on what type of org you are. While the longer term customization is very unique, I wondered if there were some meaningful categorizations.

What would characterize the reasons why you might start with formal learning, versus performance support, versus social? My initial reaction, after working with my ITA colleagues, would be that you should start with social. As things are moving faster, you just can’t keep ahead of the game while creating formal resources, and equipping folks to help each other is probably your best bet. A second step would then likely be performance support, helping people in the moment. Formal learning would then backstop for those things that are static and defined enough, or meta- enough (more generic approaches) that there’s a reason to consolidate it.

What would characterize the reasons why you might start with formal learning, versus performance support, versus social? My initial reaction, after working with my ITA colleagues, would be that you should start with social. As things are moving faster, you just can’t keep ahead of the game while creating formal resources, and equipping folks to help each other is probably your best bet. A second step would then likely be performance support, helping people in the moment. Formal learning would then backstop for those things that are static and defined enough, or meta- enough (more generic approaches) that there’s a reason to consolidate it.

However, it occurred to me that this might change depending on the nature of the organization. So, for example, if you are in an organization with lots of new members (e.g. the military, fast food franchises), formal learning might well be your best starting point. Formal learning really serves novices best.

So when might you want to start with performance support? Performance support largely serves practitioners trying to execute optimally. This might be something like manufacturing or something heavily regulated or evidence based, like medicine. The point here would be to helping folks who know why they’re doing what they’re doing, and have a good background, but need structure to not make human mistakes.

Social really comes to it’s fore for organizations depending on continual innovation: perhaps consumer products, or other organizations focused on customer experience, as well as in highly competitive areas. Here the creative friction between individuals is the highest value and consequently needs a supportive infrastructure.

Of course, your mileage may vary, and every organization will have places for all of the above, but this strikes me as a potential way to think about where you might want to place your emphasis. Other elements, like when to do better back end integration, and when to think about enabling via mobile, will have their own prioritization schemes, such as a highly mobile workforce for the latter.

So, what am I missing?

#itashare

Assessing online assessments

Good formal learning consists of an engaging introductions, rich presentation of concepts, annotated examples, and meaningful practice, all aligned on cognitive skills. As we start seeing user-generated online c, publishers and online schools are feeling the pressure. Particularly as MOOCs come into play, with (decreasingly) government funded institutions giving online content and courses for free. Are we seeing the demise of for-profit institutions and publishers?

I will suggest that there’s one thing that is harder to get out of the user-generated content environment, and that’s meaningful practice. I recall hearing of, but haven’t yet seen, a seriously threatening repository of such. Yes, there are learning object repositories, but they’re not yet populated with a rich suite of contextualized practice.

Writing good assessments is hard. Principles of good practice include meaningful decisions, alternatives that represent reliable misconceptions, relevant contexts, believable dialog, and more. They must be aligned to the objectives, and ideally have an increasing level of challenge.

There are some technical issues as well. Extensions that are high value include problem generators and randomness in the order of options (challenging attempts to ‘game’ the assessment). A greater variety of response options for novelty isn’t bad either, and automarking is desirable for at least a subset of assessment.

I don’t want to preclude essays or other interpretive work like presentations or media content, and they are likely to require human evaluation, even with peer marking. Writing evaluation rubrics is also a challenge for untrained designers or experts.

While SMEs can write content and even examples (if they get pedagogical principles and are in touch with the underlying thinking, but writing good assessments is another area.

I’ve an inkling that writing meaningful assessments, particularly leveraging interactive technology like immersive simulation games, is an area where skills are still going to be needed. Aligning and evaluating the assessment, and providing scrutable justification for the assessment attributes (e.g. accreditation) is going to continue to be a role for some time.

We may need to move accreditation from knowledge to skills (a current problem in many accreditation bodies), but I think we need and can have a better process for determining, developing, and assessing certain core skills, and particularly so-called 21st century skills. I think there will continue to be a role for doing so, even if we make it possible to develop e necessary understanding in any way the learner chooses.

As is not unusual, I’m thinking out loud, so I welcome your thoughts and feedback.

Travel Tech

Yesterday I wrote about some products, and I thought I should also own up to the mobile apps I use while traveling (at least domestically, international is still a bloody headache). It’s something I do a fair bit, and is a natural opportunity for mobile to make your life easier and more effective.

First, the natural functions of basic apps are helpful. I put my flight details and a reminder into my calendar. 3 hours before the flight, unless it’s a connection, then 40 minutes to alert me to get to the gate (United used to have an option to automatically download it to your calendar, but that changed with the software switch on the integration with the proud bird). I also put in reservations for cars and hotels. I keep track of the confirmation number that way and don’t have to carry around an extra piece of paper. The camera is useful too, when I need to remember my parking space. Easier than entering into the calendar! And I have a password app (I use SplashID since I had it before on my Treo) where I store all my membership numbers for the loyalty programs. May as well get the benefits if you have to travel. And Google Search gets used for lots of things.

A I mentioned yesterday, Navigon is GPS software that I’ve used many a time to get from place a to place B. I try to avoid driving if at all possible (such a waste of time, give me a train any time), but when I need to in or to an unfamiliar destination, GPS is the go. These days Google Maps does a very good job too, but if you’re going somewhere with dodgy cell coverage, having maps local is nice (if battery abusive: keep a charger). Google maps in particular is very useful for walking directions and times, too.

I use the iBart app to check train schedules to and from the airport. There are lots of apps out there to facilitate using particular train systems, and I’d use Metro in other towns if I were using public transit, e.g. Boston or DC. If you live in a particular location, check and see if there’s an app for your system.

On occasions, I use SuperShuttle (I try to be frugal when time allows), and their app lets you book the trip, check on your van, etc. When needed, it’s quite useful. TaxiMagic would be used sometimes if I had trouble getting a cab (I can recall one time in Philly where it would’ve been very handy).

When I do have to drive, CheapGas helps you find the prices of petrol near you and find a provider with the best deal. Other special purpose driving apps are RoadAhead (finding things at turnouts ahead; but it would require someone else in the car with you) and the AAA and Roadside apps, which can help you find accommodation or help you with car trouble. Thankfully haven’t needed them, but nice to have.

At airports, I love GateGuru. I try to get to the airport early (I’d rather be cooling my heels with a book or an app than sweating whether I’ll make it thru security on time), and if I have time to kill or need to grab a meal or a drink, GateGuru finds the opportunities nearby and has ratings. Very helpful.

I’ve the SeatGuru app, but I tend to use the website, as it can be helpful for choosing the best seating position, particularly when you’ve got a choice and the extra considerations aren’t obvious (loud, limited recline, etc).

When I’m looking for a place to eat, Yelp can be very helpful (in fact, finding us the nice Twin Cities Grill in Minneapolis just last week). You can indicate where you are and look for what’s around. Google Maps can do this too, but Yelp’s somehow a little better, optimized as it is for this purpose. On occasion I’ll use or coordinate with UrbanSpoon.

Finally, a shoutout to United. I’ve been sucked in for years (long story, started when they were the last option when I lived in Sydney), but whether you like the service or airline or not, their app is a great example of mobile support. You can review your flights, get your boarding pass, check flight status, get your mobile QR code boarding pass, and even book a flight. Really nice job of matching user need to functionality.

So, what apps have made your life easier when you travel?

Types of thinking

Harold Jarche reviews Marina Gorbis’ new book The Nature of the Future, finding value in it. I was intrigued by one comment which I thought was relevant to organizations. It has to do with the nature of thinking.

In it, this quote struck a nerve: “Gorbis identifies unique human skills”. The list of them intrigued me:

- Sensemaking

- Social and emotional intelligence

- Novel and adaptive thinking

- Moral and ethical reasoning

While all are intriguing and important, the first and third really struck me. When I talk about digital technology (which I do a lot :), I mention how it perfectly augments our cognitive architecture. Our brains are pattern-matchers and meaning extractors. They’re really good at seeing insights. And they’re really bad at rote memory, and complex calculations.

Digital technology is exactly the reverse: it’s great at remembering rote information and in doing complex calculations. It’s extremely hard to get computers to do good pattern-matching or meaning making.

For the purposes of achieving meaningful outcomes, coupling our capabilities with digital technology makes a lot of sense. That’s why mobile makes so much sense: it decouples that complementary capability from the desktop, and untethers our outboard brain.

From an organizational point of view, you want to be empowering your people with digital augmentation. From a societal point of view, you want to have people doing meaningful tasks where they tap into human capability, and not doing rote tasks. They’re going to be bad at it! And, you can infer, it’s also the case that you’re going to want education to focus on how to do problem-solving and using digital technology as an augment, not on doing rote things and memory tasks. Ahem.

Designing Higher Learning

I’ve been thinking a lot about the higher education situation, specifically for-profit universities. One of the things I see is that somehow no one’s really addressing the quality of the learning experience, and it seems like a huge blindspot.

I realize that in many cases they’re caught between a rock and a hard place. They want to keep costs down, and they’re heavily scrutinized. Consequently, they worry very much about having the right content. It’s vetted by Subject Matter Experts (SMEs), and has to be produced in a way that, increasingly, it can serve face to face (F2F) or online. And I think there’s a big opportunity missed. Even if they’re buying content from publishers, they are focused on content, not experience. Both for the learner, and developing learner’s transferable and long-term skills.

First, SMEs can’t really tell you what learners need to be able to do. One of the side-effects of expertise is that it gets compiled away, inaccessible to conscious access. Either SMEs make up what they think they do (which has little correlation with reality) or they resort to what they had to learn. Neither’s a likely source to meaningful learning.

Even if you have an instructional designer in the equation, the likelihood that they’re knowledgeable enough and confident enough to work with SMEs to get the real outcomes/objectives is slim. Then, they also have to get the engagement right. Social engagement can go a good way to enriching this, but it has to be around meaningful tasks.

And, what with scrutiny, it takes a strong case to argue to the accrediting agencies that you’ve gone beyond what SMEs tell you to what’s really needed. It sounds good, but it’s a hard argument to an organization that’s been doing it in a particular way for a long time.

Yet, these institutions also struggle with retention of students. The learners don’t find the experience relevant or engaging, and leave. If you took the real activity, made it meaningful in the right way, learners would be both more engaged and have better outcomes, but it’s a hard story to comprehend, and perhaps harder yet to implement.

Yet I will maintain that it’s both doable, and necessary. I think that the institution that grasps this, and focused on a killer learning experience, coupled with going the extra mile to learner success (analytics is showing to be a big help here), and developing them as learners (e.g, meta-learning skills) as well as performers, is going to have a defendable differentiator.

But then, I’m an optimist.

Robinsons’ Performance Consulting

As a consequence of my previous post and the commented revelation, I checked out the Robinsons’ Performance Consulting. The book really takes a different approach to what I was talking about so I suppose it’s worth delineating the difference.

What I was talking about was how learning & development groups should be looking not only to courses, but also performance support and social media as components of potential solutions to organizational needs. It naturally includes a focus on aligning with business needs, but takes a rich picture of opportunities to have impact.

The Robinsons’ book is more focused on ensuring the project you’re working on is addressing the real problem. It rightly has you stepping back to look at the business problem (the gap between how things should be, and how they are), and the reasons why these gaps exist. Then, you should be designing solutions that address all the needs, and systematically solve the problem.

There are two really good things about their approach. The focus on the real problem is designed to prevent using a solution that may be familiar, but may not really solve the problem. This was similar to my complaint. The other thing is they’re willing to go beyond courses for solutions, looking at incentives, job aids, work process redesign, etc.

On the other hand, it’s not clear to me that they would be able to incorporate potential social solutions in their repertoire. When should you have people go to their network? An interesting question, but not one that obviously flows out of their approach.

Regardless, I think the rigor of the book (and it’s nicely complemented by exercises, examples, etc.) makes it a worthy contribution. I suspect that too many L&D groups might not be willing to push as hard as needed to make sure that the solution being developed is pointed to by a thorough analysis (as many of their examples point out), and this book gives you guidance and tools to do the job. There’re also some end chapters on being a successful consultant that could be valuable to practitioners as well. Well worth a read.