It turns out that I’ve been to a lot of conferences this year (8, if my math is right) scattered through the year and around the globe. And over the past decade, I’ve hit a lot more. And it’s given me some opportunities to contrast and compare some of the tradeoffs that can be made. So I thought I’d share my thoughts with you.

Now, my perspective starts out a bit different. At these events, I’m speaker, so I see things from a different perspective. However, I also try to go see sessions as an audience member as well, and I still see the same events. So I am trying to write this from all perspectives: conference organizer, attendee, speaker, and vendor. And let me be clear, I’m a learning technology strategist, and my passions are learning, technology, and how to use them together to make things better. So that colors my comments.

Here are the major elements and my thoughts on them:

Keynotes: I am tired of ‘inspirational’ keynotes. I really don’t need to hear some person who climbed a mountain or sailed a sea and their attempts to connect that to learning somehow. I’d rather hear about an issue that affects learning. Topics about how we think, work, or learn are of interest. Let’s hear about the risks of technology, or some new ones or ways to use them. Yes, I like compelling speakers, but please give me new thoughts, not random aspiration.

Speakers: I think it’s unconscionable to have an unprepared speaker who can’t manage time. It’s even worse on panels or shared sessions where one speaker runs over. It’s just not fair to the other speakers. It’s also essential that the talk is not a sales pitch, but instead presents real value in ideas or experience. And they should be happy to chat afterward. It boggles my little mind when someone gets up and clearly hasn’t practiced and checked their timing. It’s appears I’m somewhat unusual, but I really don’t necessarily feel the critical need to spend most of the time conversing with others. I don’t mind, and even can recommend some interaction, but I want to hear something substantive as well.

Schedule: I like events that have a clear and comprehensible schedule. I want to know exactly what things are at the same time, so I can choose and then vote with my feet if the first choice isn’t working for me. Having different tracks have different schedules doesn’t work. And as a speaker and an attendee, I don’t like short sessions. Give me at least an hour as a speaker to set the tone, present the topic, talk about the issues and tradeoffs, and talk about the way forward. Similarly as an audience member, I want suitable depth. 30 minutes just isn’t enough.

Breaks: And then I want a break. The break should be long enough to potentially chat with the speaker at the preceding event, get out and find some sustenance, use the facilities, have a conversation or two, and get to the next event. Workshop breaks can be shorter, as you’re with a group for a half or full day, but for separating concurrent sessions, they need to be sufficiently long.

Events: I love having social events, as a way to have those important serendipitous conversations. An evening reception after the first day is mandatory. I like sufficient nibbles to fend off the need to escape to dinner, or dinner actually provided. And for the end of the day, I like social lubricant. Preferably on demand, not via a limited ration. It doesn’t have to be a broad selection, but not having to worry about logistics means my mind is free to focus on conversations. I assume lunch is provided, of course, and it doesn’t have to be fancy or rich, just healthy, substantive, and reasonably tasty. Other events, such as mid afternoon treat breaks, and mid morning snack breaks are great. I really like it if some form of breakfast is available as well. I think I’m not the only one who prefers to eat little bits over time, not big meals.

Expo Hall: I like to have an exhibition. I like to see what’s around. Yes, I don’t like walking past and being grabbed, but I do like it if I can go up, have an intelligent conversation about the problem solution, and not feel pressured. I like to see the alternatives, and take the temperature of the market. And I like people who might have real needs to be able to explore real solutions. Having events in the expo area makes sense to me and the vendors.

App: I used to get a PDF of the program and put it on my tablet. Now I am happy using an app, and it’s become a must-have. I like it when I can choose sessions for my schedule and have reminders. I like having a stream of information, though it could be via Twitter. I like having an expo map if the expo is of any size at all. And I don’t really care for gamification to reward participation. While I like the engagement of users, it leads to too many frivolous posts. I really like it if presentation material is available through the app, and happy to do evaluations that way.

Bookstore: I think a bookstore is important, for several reasons. For one, you can get a heads up on a speaker before you see them. Or if you miss a session, you can graze what you might have missed. You might also want to get the works of someone who you really were intrigued by. It’s also a way to see what’s happening in the field.

Rest areas: I don’t really need speaker prep. Sometimes it may be handy if the event is really big, but the main things is, instead, having good connection to event staff. And I think that’s true for all, not just speakers. Having places to sit for all attendees means that anyone needing a break whether social or physical can achieve that end.

People: The staff makes quite a big difference when they’re knowledgeable and helpful. This has almost always been the case, but it’s nice to have informed people ready and willing to help. This is true for vendors as well, having friendly and knowledgeable people trumps having shills who can chat you up but can’t really answer questions.

So, what have I forgotten to address?

I realize that there are different audiences, purposes, and business models for these events, and so not all things are comparable. And this is also my opinion, and your motives may differ, but I hope I’ve laid out some of the thinking to help you think about what works for you. And I hope to see you at a conference sometime!

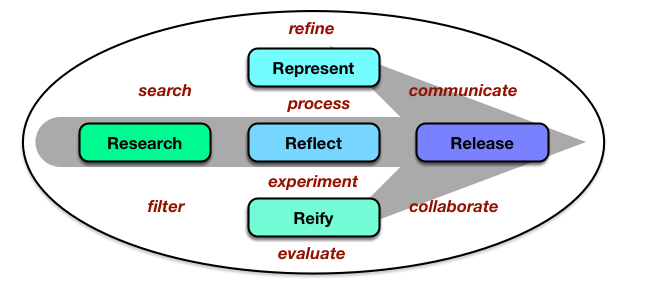

The core is the 5 R’s: Researching the opportunities, processing your explorations by either Representing them or putting them into practice (Reify) and Reflecting on those, and then Releasing them. And of course it’s recursive: this is a release of my representation of some ideas I’ve been researching, right? This is very much based on Harold Jarche’s

The core is the 5 R’s: Researching the opportunities, processing your explorations by either Representing them or putting them into practice (Reify) and Reflecting on those, and then Releasing them. And of course it’s recursive: this is a release of my representation of some ideas I’ve been researching, right? This is very much based on Harold Jarche’s