An organization that I cited in the Revolution book, Towards Maturity, has recently released their 2015-2016 Industry Benchmark Report, and it’s of interest to individuals and organizations looking for real data on what’s working, and not, in L&D. Towards Maturity has been collecting benchmarking data on L&D practices for over a decade, and what they find bolsters the case to move L&D forwards.

The report has a number of useful sections, including documenting the current state of the industry, guidance for business leaders on expectations, on listening to learners, and on rethinking the L&D team. Included are some top level pointers for executives and L&D. And while the report is biased towards Europe, respondents cover the globe including Asia, Americas, and more.

Overall, they’re finding a 19% average in technology spending out of L&D budgets (and this has been essentially flat for 3 years). This seems light; given that technology is a key enabler of performance and development, such a figure doesn’t seem appropriate. Of course, given that 55% of formal learning is still delivered face-to-face, this isn’t surprising.

A more interesting outcome is comparing what they call Top Deck organizations; those in the top 10% of their Towards Maturity Index. These organizations are characterized by four elements that are tied to success:

- Learning aligned to need

- Active learner voice

- Design beyond the course

- Proactive in connecting

Here we see key elements of the revolution. For one, learning isn’t done on demand, but is coupled to organizational improvements. For another, the learner is engaged in the processes of determining what solutions make sense. One that intrigues me is that the solutions go beyond courses, looking at performance support and more. And finally, L&D is reaching out across silos to engage in conversations. These are all key to achieving results from 6 – 8 times the average organization.

The advice to business leaders also echoes the revolution. The call is to focus on performance, not on courses. It’s not about learning, it’s about outcomes. The recommendation is to break down silos so as to achieve the conversations that will achieve meaningful impact.

The advice goes on: understand how learners are learning, create a participatory culture, and use real business metrics. All grounded in what successful organizations are doing. The point here is not to recite all the outcomes, but instead to list highlights and encourage you to have a look at the report. Going forward, you might even consider benchmarking your own organization!

Benchmarking is best practices, and of course I encourage best principles, but the frameworks they use are grounded in the best principles, and measuring yourself against the framework and improving is really more important than comparing yourself to others. I will suggest that measuring yourself and evaluating your progress is a valuable investment of time in conjunction with a strategy.

What I really like, of course, is that the data support the position posited by principles that I derived from both practical experience and relevant conceptual models. The evidence is converging that there are positive steps L&D can, and should, take. The revolution provides the roadmap, and their data provides a way to evaluate progress. Here’s to improving L&D!

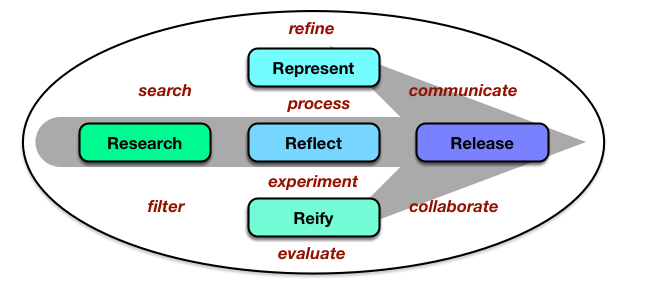

The core is the 5 R’s: Researching the opportunities, processing your explorations by either Representing them or putting them into practice (Reify) and Reflecting on those, and then Releasing them. And of course it’s recursive: this is a release of my representation of some ideas I’ve been researching, right? This is very much based on Harold Jarche’s

The core is the 5 R’s: Researching the opportunities, processing your explorations by either Representing them or putting them into practice (Reify) and Reflecting on those, and then Releasing them. And of course it’s recursive: this is a release of my representation of some ideas I’ve been researching, right? This is very much based on Harold Jarche’s