I’ve been attending the CLO Fall Symposium this week, and it’s been a great experience. I wrote it up as a blog post over at eLearn Mag. There is supposed to be more linkage between Learnlets and their mag real soon. Stay tuned!

Archives for September 2009

Virtual Worlds: Affordances and Learning

Two days ago I attended the 3D Teaching, Learning, & Collaboration conference, organized by Tony O’Driscoll. I’ve previously posted my thoughts on virtual worlds, but I had a wee bit of a revelation that I want to get clear in my head, and it ties into several things that went on at the conference.

First, let me say that the day of the conference I got to attend was great, with lots of the really involved folks there, and every evidence (including the tweet stream) that the second day was every bit as good. Tony talked about his new book with Karl Kapp, Chuck Hamilton spoke on lessons learned through IBM’s invovlement in Virtual Worlds, Koreen Olbrish chaired a panel with a number of great case studies, to name just a few of the great opportunities.

Chuck listed 10 ‘affordances‘ of virtual worlds, expanding a list Tony had previously started. There was some debate about whether affordance is a good term, since not everyone knows it, but I maintain that for people who need it, it’s the right term and that we can use some term like ‘inherent capability’ for those who don’t. I had some quibbles with Chuck’s list, as it seemed that several confounded some issues, and I hope to talk with him more about it.

Tony also presented, in particular, some principles about designing learning for virtual worlds (see slide 17 here). Interestingly, they aren’t specific to virtual worlds, and mirror the principles for designing engaging learning experiences that come from the alignment of educational practice and engaging experiences I talk about in my book. Glad to see folks honing in on principles for creating meaningful virtual world experiences!

The revelation for me, however, was linking the social informal learning with virtual worlds. Virtual worlds can be used for both formal and informal learning, they’re platforms for social action. I’ve had the formal and informal separated in my mind, but needn’t. I’ve been quite active in social learning to meet informal learning needs with my togetherLearn colleagues, but have always written off virtual worlds as still having too much technical and learning overhead to be worth it unless you have a long-term intention where those overheads get amortized.

What’s clear is that, increasingly, organizations are creating and leveraging those long term relationships. ProtonMedia even announced integration of both Sharepoint and their own social media system with their virtual world platform, so either can be accessed in world or from the desktop. There were a suite of examples across both formal and informal learning where organizations were seeing real, measurable, value.

The underlying opportunities of virtual presence are clear, it’s just not been clear that it’s significantly better than a non-immersive social networking system. Certainly if what your people need to formally learn, or informally network on is inherently 3D, but the contextualization is having some benefits.

Some issues remain. At lunch I was talking to some gents who have a system that streams your face via webcam onto your avatar, so your real expressions are represented. That’s counter to some of the possibilities I see to represent yourself in virtual worlds as you prefer to be seen, not as how nature commands, but there are some trust issues (and parental safety concerns as well).

Still, as technical barriers are surpassed, and audiences become more familiar with and comfortable in virtual worlds, the segue between formal and social networking can be accomplished in world making a virtual business office increasingly viable. It may be time to dust off my avatar and get traveling.

The 7 c’s of natural learning

Yesterday I talked about the seeding, feeding, and weeding necessary to develop a self-sustaining network. I referred to supporting the activities that we find in natural learning, for both formal and informal learning. The goal is to align our organized support with our learners to optimize the outcome. In thinking about it (and borrowing heavily from some slides by Jay Cross), I discerned (read: worked hard to fit :) 7 C’s of learning that characterize how we learn before schooling extinguishes the love of learning:

Choose: we are self-service learners. We follow what interests us, what is meaningful to us, what we know is important.

Commit: we take ownership for the outcomes. We work until we’ve gotten out of it what we need.

Crash: our commitment means we make mistakes, and learn from them.

Create: we design, we build, we are active in our learning.

Copy: we mimic others, looking to their performances for guidance.

Converse: we talk with others. We ask questions, offer opinions, debate positions.

Collaborate: we work together. We build together, evaluate what we’re doing, and take turns adding value.

With this list of things we do, we need to find ways to support them, across both formal and informal learning. In formal learning, we should be presenting meaningful and authentic tasks, and asking learners to solve them, ideally collaboratively. While individual is better than none, collaborative allows opportunity for meaning negotiation. We need to allow failure, and support learning from it. We need to be able to ask questions, and make decisions and see the consequences.

Similarly in informal learning, we need to create ways for people to develop their understandings, work together, to put out opinions and get feedback, ask for help, and find people to use as models. By using tools like blogs for recording and sharing personal learning and information updates, wikis to collaborate, discussion forums to converse, and blogs and microblogs to track what others think are important, we provide ways to naturally learn together.

Recognize that I’m taking the larger definition of learning here. I do not mean just courses, though they’re part of it. However, real learning involves research, design, problem-solving, creativity, innovation, experimentation, etc. We absolutely have to get our and the organization’s mind around this if we’re going to be effective. So, look to natural learning to guide your role in facilitating organizational learning.

Seed, feed, & weed

In my presentation yesterday, I was talking about how to get informal learning going. As many have noted, it’s about moving from a notion of being a builder, handcrafting (or mass-producing) solutions, to being a facilitator, nurturing the community to develop it’s own capabilities. Jay Cross talks about the learnscape, while I term it the performance ecosystem. The point, however, is from the point of the view of the learner, all the resources needed are ‘to hand’ through every stage of knowledge work. Courses, information resources, people, representational tools, the ability to tap into the 4 C’s (create, contextualize, connect, co-create).

Overall, it taps into our natural learning, where we experiment, reflect, converse, mimic, collaborate, and more. Our approach to formal learning needs to more naturally mimic this approach, having us attempting to do something, and resourcing around it with information and facilitation. Our approach to informal learning similarly needs to reflect our natural learning.

Networks grow from separate nodes, to a hierarchical organization where one node manages the connections, but the true power of a network is unleashed when every node knows what the goal is and the nodes coordinate to achieve it. It is this unleashing of the power of the network that we want to facilitate. But if you build it, they may not come.

Networks take nurturing. Using the gardener or landscaper metaphor, yesterday I said that networks need seeding, feeding, and weeding. What do I mean? If you want to grow a network, you will have to:

Seed: you need to put in place the network tool, where individuals can register, and then create the types of connections they need. They may self-organize around roles, or tasks, or projects, or all of the above. They may need discussion forums, blogs, wikis, and IM. They may need to load, tag, and search on resources. You likely will need to preload it with resources, to ensure there’s value to be found. And you’ll have to ensure that there are rewards for participating and contributing. The environment needs to be there, and they have to be aware.

Feed: you can’t just put in place, you have to nurture the network. People have to know what the goals are and their role. Don’t tell them what to do, tell them what needs done. You may need to quietly ‘encourage’ the opinion makers to participate. And the top of the food chain needs to not only anoint the process, but model the behavior as well. The top level of the group (ie not the CEO, but the leader of whatever group you’ve chosen to facilitate) needs to be active in the network. You may need to highlight what other people have said, elicit questions and answers, and take a role both within and outside the network to get it going. You may have to go in and reorganize the resources, take what’s heard and make it concrete and usable. You’ll undoubtedly have to facilitate the skills to take advantage of the environment. And you have to ensure there’s value there for them.

Weed: you may have to help people learn how to participate. You may well find some inappropriate behavior, and help those learn what’s acceptable. You’ll likely have to develop, and modify, policies and procedures. You may have to take out some submitted resources and revise them for better usability. You may well have to address cultural issues that arise, when you find that participation is stunted by a lack of tolerance of diversity, no openness to new ideas, no safety for putting ideas out, and other factors that facilitate a learning organization.

However, if you recognize that it will take time and tuning, and diligently work to nurture the network, you should be able to reap the benefits of an aligned group of empowered people. And those benefits are real: innovation, problem-solving, and more, and those are the key to organizational competitiveness going forward. Ready to get grubby?

What’s an ‘A’ for?

I was recently thinking about grades, and was wondering what an ‘A’ means these days. Then, at my lad’s Back to School night, I was confronted with evidence of the two competing theories that I see. One teacher had a scale on the wall, with (I don’t remember exactly, but something like): 96-100 = A+, 91-95 = A, 86-90 = A-, and so on, down to below 50 = Fail. Now, you get full points on homework just for trying, but it’s clearly a competency model, with absolute standards. A different teacher recounted how she tells students that if they just do the required work, that it’s only worth a C, and A’s are for above and beyond. That’s a different model. There aren’t strict criteria for that latter. And I’m very sympathetic to that latter stance, despite that it seems subjective.

The second approach resonates with my experience back in high school, where A’s were handed out for work that really was above and beyond the ordinary. A deeper understanding. We seem to have shifted to a model where if you do what’s asked, you get an ‘A’. And I see benefits of both sides. Defining performance, and having everyone able to achieve them is ideal. Yet, intuitively, you recognize that there’s the ability to apply concepts, and then another level where people can flexibly use them to solve novel problems, combine them with other concepts, infer new concepts, etc.

I was pointed to some work by Daniel Schwartz (thanks @mrch0mp3rs) that grounds this intuition in an innovative framework based upon some good research. In a paper with John Bransford and David Sears, they made a intriguing case for two different forms of transfer: efficient and innovative, and argued convincingly that most of our models address the former and not the latter, yet addressing the latter yielded better outcomes on both. I think the work David Jonassen is doing on teaching problem-solving is developing just this sort of understanding, but it’s on problems that are like real world ones (and yet improves performance on standard measures). And I like David’s lament that the problems kids solve in schools have no relation to the problems they see in the world (and, implicitly, no worth).

Right now, our competencies aren’t defined well enough to support assessing this extra level. In an ideal world, we’d have them all mapped out, and you could get A’s in every one you could master. We don’t live in that world, unfortunately. So we have two paths. We live with our lower measures, and everyone gets A’s meeting them (if they try, but that’s a separate issue), and then sort it out after graduation, in the real world, or we allow some interpretation by the teacher and measure not only effort, but a deeper form of understanding. We’ve steered away from the second approach, probably because of the consequent arguments about favoritism, social stigma, etc. Yet the former is increasingly meaningless, I fear.

We should bite the bullet and admit that we’re waving our hands. Then we could own up that not all teachers are ready to do the type of teaching David’s doing and Daniel’s advocating, and look to using technology to make available a higher quality of content (like the UC College Prep program has been doing) to provide support. I’d rather see a man-in-the-moon program around getting a really meaningful curriculum up online than going to Mars at this point, and I’m a big fan of NASA and the pragmatic benefits of space exploration. Just think such a project would have a bigger impact on the world, all told.

In the meantime, we have to live with some grade inflation (gee, I got into a UC with a high school average below 4.0!), bad alignment between what schools do and what kids need as preparation for life in this century, and a very long road towards any meaningful change. Sigh.

Design, processes, and ADDIE

I come to check briefly on what’s happening, late on an evening, and find a flurry of discussion that prompts reflection. It’s been an ongoing debate, with notables like Ellen Wagner and Brent Schlenker weighing in. In reading another post pointed to by Cammy Bean, I see a cogent discussion of how processes can be stifling or supportive.

I was reminded of a story told many years ago on a listserve, where both new and experienced (10 years) graduates of several ID programs were asked to design projects. The projects by the new graduates were categorizable by school. The projects by the experienced graduates were not, until the accompanying rationales were read. This was never published, unfortunately, but even as an apocryphal story, it’s instructive.

The point being, that the processes we learn are scaffolds for performance. ADDIE is a guide to help ensure hitting all the important points. It’s no guarantee of a good design. It takes understanding the nuances (see Broken ID), and some creativity.

Used appropriately, ADDIE reminds us to dot our i’s and cross our t’s. We ensure an adequate analysis of need (cf HPT), appropriate attention to design and development, care about the implementation, and ensure evaluation. Used inappropriately, we pay lip service to the stages, doing the same cookie-cutter process we butcher when we do bad ID.

So, to my point: ADDIE’s not broken, but the way it’s used is. It’s supposed to be used as a guide, which is fine. However, it’s being used as a crutch, and that’s wrong. The question is, do we impugn the approach because of it’s implementation, as a way to draw attention to the misuse, or only malign the misuse? I’m not sure the latter’s sufficient, nor the former is fair.

So, I say let the debate rage. We need a resolution, but I fear that there aren’t sufficient resources concerted to a) bring together the necessary conceptual inputs, b) to support the debate, and c) to advocate any outcomes. There are broader issues to be talking about, such as how a design process plays out when we consider not just novices, but practitioners and experts, including performance support and social/informal. We’ve some breakdowns conceptually, and then pragmatically in implementation.

I’ll echo Brent’s call to bring the issue to DevLearn, and see where we get. At least, a lot of us will be there!

Driving formal & informal from the same place

There’s been such a division between formal and informal; the fight for resources, mindspace, and the ability for people to get their mind around making informal concrete. However, I’ve been preparing a presentation from another way of looking at it, and I want to suggest that, at core, both are being driven from the same point: how humans learn.

I was looking at the history of society, and it’s getting more and more complex. Organizationally, we started from a village, to a city, and started getting hierarchical. Businesses are now retreating from that point of view, and trying to get flatter, and more networked.

Organizational learning, however, seems to have done almost the opposite. From networks of apprenticeship through most of history, through the dialectical approach of the Greeks that started imposing a hierarchy, to classrooms which really treat each person as an independent node, the same, and autonomous with no connections.

Certainly, we’re trying to improve our pedagogy (to more of an andragogy), by looking at how people really learn. In natural settings, we learn by being engaged in meaningful tasks, where there’re resources to assist us, and others to help us learn. We’re developed in communities of practice, with our learning distributed across time and across resources.

That’s what we’re trying to support through informal approaches to learning. We’re going beyond just making people ready for what we can anticipate, and supporting them in working together to go beyond what’s known, and be able to problem-solve, to innovate, to create new products, services, and solutions. We provide resources, and communication channels, and meaning representation tools.

And that’s what we should be shooting for in our formal learning, too. Not an artificial event, but presented with meaningful activity, that learners get as important, with resources to support, and ideally, collaboration to help disambiguate and co-create understanding. The task may be artificial, the resources structured for success, but there’s much less gap between what they do for learning and what they do in practice.

In both cases, the learning is facilitated. Don’t assume self-learning skills, but support both task-oriented behaviors, and the development of self-monitoring, self learning.

The goal is to remove the artificial divide between formal and informal, and recognize the continuum of developing skills from foundational abilities into new areas, developing learners from novices to experts in both domains, and in learning..

This is the perspective that drives the vision of moving the learning organization role from ‘training’ to learning facilitator. Across all organizational knowledge activities, you may still design and develop, but you nurture as much, or more. So, nurture your understanding, and your learners. The outcome should be better learning for all.

Facilitating Learning

In last night’s #lrnchat on instructional design,there was some discussion of the term ‘learning facilitator’ versus ‘trainer’ (which now I can’t find!?!), and it got me wondering. I’ve also been thinking about a set of talks I may be giving, and how to break them up. There was also a discussion on ITFORUM that expanded to discuss how experts are losing the problem-solving skills and how to develop them. It leads me to think about what is learning, and why we are arguing that the new role in the organization will be for learning facilitation, not for ‘instruction’ or ‘training’.

How do we learn? Not how do we believe we should be instructed, but how do we learn? If we look at anthropology, empirical studies, psychology and more, the ideal learning happens when learners get why they’re learning, are working on meaningful tasks, have support around, are given time to reflect, and more. Recourse to knowledge resources like tapes, videos, texts, etc, is driven by need, not pre-determined. It happens best when the task has a level of ambiguity where learners collaborate to understand. There’s problem-solving, experimentation and evaluation, and more.

This happens naturally among communities of practice, and so for much of organizational learning, creating an environment where this can happen around organizational goals is really the ‘informal learning’ Jay Cross talked about in his book on the topic. Whether you want to call the actual deliberate support of informal learning ‘non-formal’ or not (I’m not hot on the idea, but can see how it might help some folks get their mind around it). However, I do strongly want to suggest that supporting informal learning in systematic ways is one of the highest value investments an organization can make in being nimble, agile, innovative, and consequently successful.

Then, we go back and look at situations where we have new folks, including folks moving to new areas (practitioners promoted to managers, where they’re new to management), new processes are introduced (whether in sales approach, new technology in a product, or new service), and people wanting to reskill. This is more about execution, and is formal learning, where we need to support motivation and manage anxiety as well as develop new skills. The point is, for the novice to practitioner transition, we need the formal treatment, whereas practitioner to expert transition is more informal, and even information can be instruction and sufficient.

When we have this formal situation, we often do the information, example, practice routine, that’s been shown to work. However, newer pedagogies, where we put meaningful tasks up front, and organize the learning around it, making it structurally closer to the more natural learning model, is proving valuable. Call it a social constructivist, or connectivist, or any other pedagogical framework. What you do is carefully structure the task to be meaningful and obviously important to the learner, carefully control the challenge, and scaffold support for the knowledge and resources. This, really, is taking instructional design in a new direction, still requiring design, but using a new pedagogy that’s more learning facilitation than ‘training’. It may be that that’s not what folks think of as training, and ideally training is more learning facilitation, but I find the relabelling to help convey the necessary approach as ‘trainer’ can unfortunately be ‘spray and pray’ or ‘show up and throw up’, at least in practice.

Note that this facilitation needs to address something more, both formally and informally. You have to develop the ability to learn in this way – the problem representation, information access, and experimentation skills – not take it for granted. Not everyone is a good self- or group-learner, and yet you want them to get better at this for the informal learning to really be optimal. Make those skills explicit, and scaffold that development as well!

No one said it’s easy, but it seems to me a more robust, important, and valuable contribution to make, a task to be proud of. That’s why many of us are now suggesting that the learning role in an organization will move to facilitation from an information presentation and testing role. Knowledge is not what’s going to be useful going forward, but skills in applying that knowledge. So my suggestion is to start thinking about facilitating learning, and abandon a focus on knowledge development. That’s where I think instructional design has to go, and I think others are seeing and saying it too. Are you?

Learning Experience Creation Systems

Where do the problems lie in getting good learning experiences? We need them, as it’s becoming increasingly important to get the important skills really nailed, not just ‘addressed’. It’s not about dumping knowledge on someone, or the other myriad ways learning can be badly designed. It’s about making learning experiences that really deliver. So, where does the process of creating a learning experience go wrong?

There’s been a intriguing debate over at Aaron (@mrch0mp3rs) Silver’s blog about where the responsibility lies between clients and vendors for knowledge to ensure a productive relationship. One of the issues raised (who, me?) is understanding design, but it’s clearly more than that, and the debate has raged.

Then, a post in ITFORUM asked about how to redo instructor training for a group where the instructors are SMEs, not trainers, and identified barriers around curriculum, time, etc. What crystallized for me is that it’s not a particular flaw or issue, but it’s a system that can have multiple flaws or multiple points of breakdown.

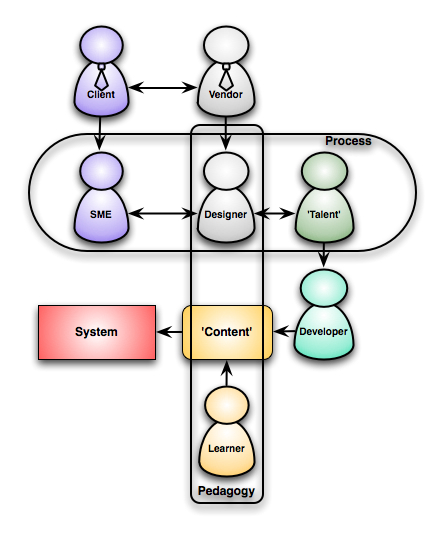

The point is, we have to quit looking at it as design, development, etc; and view it not just as a process, but as a system. A system with lots of inputs, processes, and places to go wrong. I tried to capture a stereotypical system in this picture, with lots of caveats: clients or vendors may be internal or external, there may be more than one talent, etc, it really is a simplified stereotype, with all the negative connotations that entails.

The point is, we have to quit looking at it as design, development, etc; and view it not just as a process, but as a system. A system with lots of inputs, processes, and places to go wrong. I tried to capture a stereotypical system in this picture, with lots of caveats: clients or vendors may be internal or external, there may be more than one talent, etc, it really is a simplified stereotype, with all the negative connotations that entails.

Note that there are many places for the system to break even in this simplified representation. How do you get alignment between all the elements? I think you need a meta-level, learning experience creation system design. That is, you need to look at the system with a view towards optimizing it as a system, not as a process.

I realize that’s one of the things I do (working with organizations to improve their templates, processes, content models, learning systems, etc), trying to tie these together into a working coherent whole. And while I’m talking formal learning here, by and large, I believe it holds true for performance support and informal learning environments as well, the whole performance ecosystem. And that’s the way you’ve got to look at it, systemically, to see what needs to be augmented to be producing not content, not dry and dull learning, not well-produced but ineffective experiences, but the real deal: efficient, effective, and engaging learning experiences. Learning, done right, isn’t a ‘spray and pray’ situation, but a carefully designed intervention that facilitates learning. And to get that design, you need to address the overall system that creates that experience.

The client has to ‘get’ that they need good learning outcomes, the vendor has to know what that means. The designer/SME relationship has to ensure that the real outcomes emerge. The designer has to understand what will achieve these outcomes. The ‘talent’ (read graphic design, audio, video, etc) needs to align with the learning outcomes, and appropriate practices, the developer(s) need to use the right tools, and so on. There are lots of ways it can go wrong, in lack of understanding, in mis-communication, in the wrong tools, etc. Only by looking at it all holistically can you look at the flows, the inputs, the processes, and optimize forward while backtracking from flaws.

So, look at your system. Diagnose it, remedy it, tune it, and turn it into a real learning experience creation system. Face it, if you’re not creating a real solution, you’re really wasting your time (and money!).