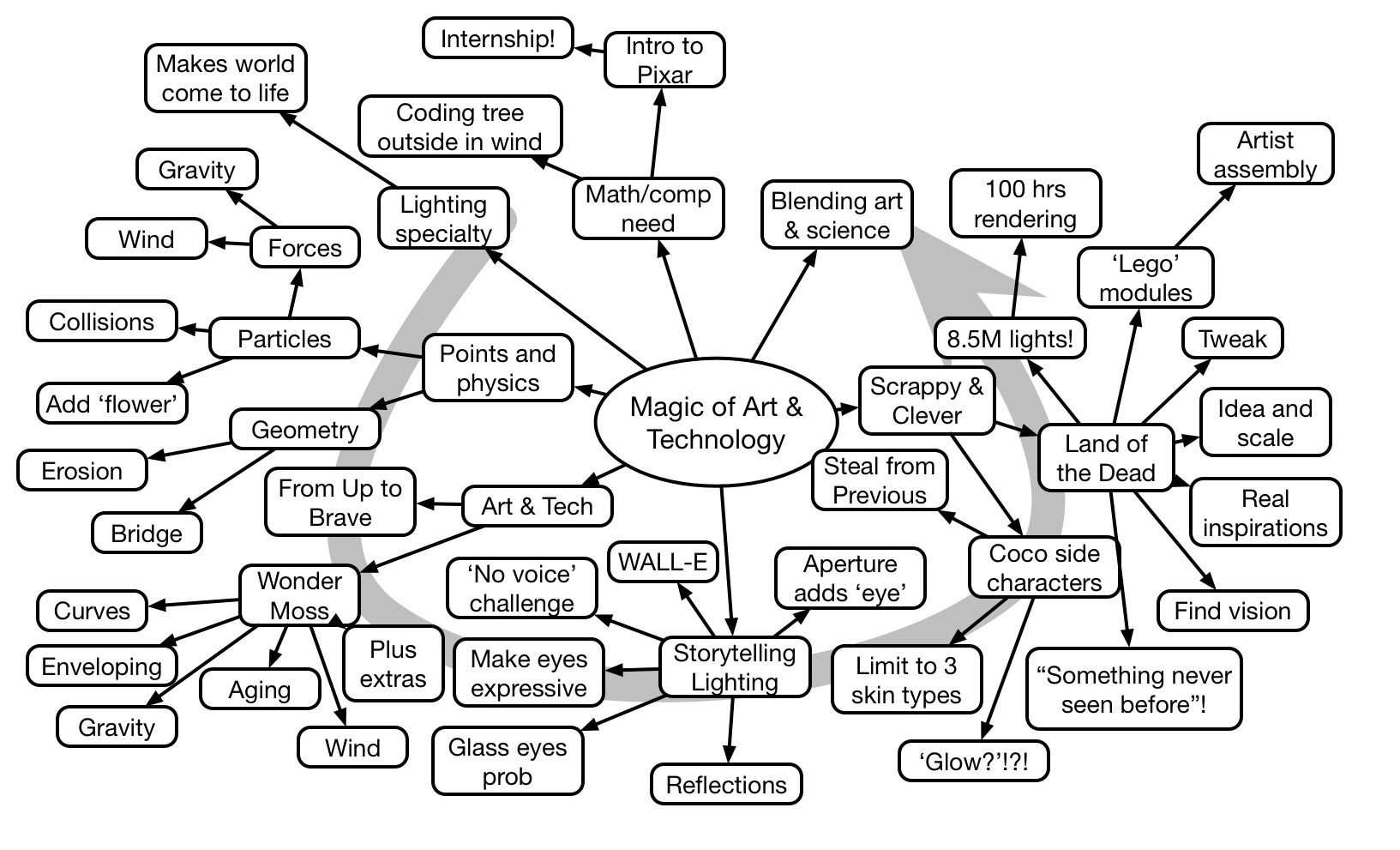

Danielle Feinberg of Pixar shared her story of using computer science to create the visual art and storytelling for Pixar movies. She illustrated the process of being creative under constraints by being ‘scrappy and clever’. She also illustrated the process with representations of intermediate stages and the stunning results from the movies. Inspiring, as hard to capture in a mindmap.

Archives for February 2019

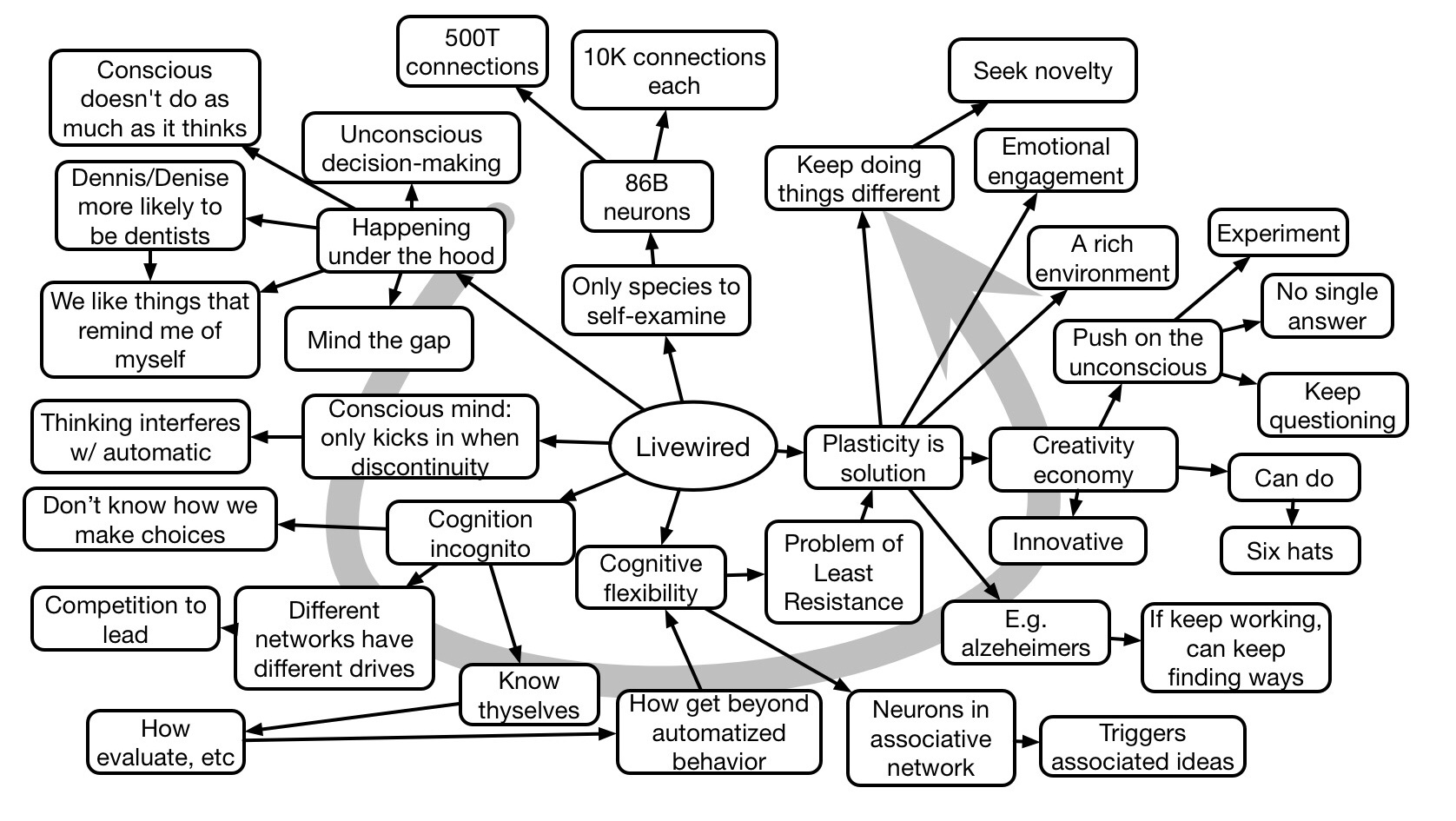

David Eagleman #Trgconf Keynote Mindmap

David Eagleman gave a humorous and insightful keynote at the Training 19 conference. He helped us see how the unconscious relates to conscious behavior, and how to break out and tap into creativity. Here’s my mindmap:

Surprise, Transformation, & Learning

Recently, I came across an article about a new explanation for behavior, including intelligence. This ‘free energy principle’ claims that entities (including us) “try to minimize the difference between their model of the world and their sense and associated perception”. To put it in other words, we try to avoid surprise. And we can either act to put the world back in alignment with our perceptions, or we have to learn, to create better predictions.

Recently, I came across an article about a new explanation for behavior, including intelligence. This ‘free energy principle’ claims that entities (including us) “try to minimize the difference between their model of the world and their sense and associated perception”. To put it in other words, we try to avoid surprise. And we can either act to put the world back in alignment with our perceptions, or we have to learn, to create better predictions.

Now, this fits in very nicely with the goal I’d been trying to talk about yesterday, generating surprise. Surprise does seem to be a key to learning! It sounds worth exploring.

The theory is quite deep. So deep, people line up to ask questions of the guy, Karl Friston, behind it! Not just average people, but top scientists need his help. Because this theory promises to yield answers to AI, mental illness, and more! Yet, at core, the idea is simply that entities (all the way down, wrapped in Markov blankets, at organ and cell level as well) look to minimize the differences between the world and their understanding. The difference that drives the choice of response (learning or acting) is ‘surprise’.

This correlates nicely with the point I was making about trying to trigger transformative perceptions to drive learning. This suggests that we should be looking to create these disturbances in complacency. The valence of these surprises may need to be balanced to the learning goal (transformative experience or transformative learning), but if we can generate an appropriate lack of expectation and outcome, we open the door to learning. People will want to refine their models, to adapt.

Going further, to also make it desirable to learn, the learner action that triggers the mismatch likely should be set in a task that learners viscerally get is important to them. The suggestion, then, is create a situation where learners want to succeed, but their initial knowledge shows that they can’t. Then they’re ready to learn. And we (generally) know the rest.

It’s nice when an interest in AI coincides with an interest in learning. I’m excited about the potential of trying to build this systematically into design processes. I welcome your thoughts!

Transformative Learning & Transformative Experiences

In my quest to not just talk about transformation but find a way to go beyond just experience, I did some research. I came across a mention of transformative experiences. And that, in turn, led me to transformation learning. And the distinction between them started me down a path that’s still evolving. Practicing what I preach, here’s how my thinking’s developing.

I’ll start with the reverse, transformative learning, because it came first and it’s at the large end. Mezirow was the originator of Transformative Learning Theory. It’s addressing big learnings, those that come about from a “disorienting dilemma”. These are life-changing events. And we do want to be able to accommodate this as well, but we might also need something more, er scalable. (Do we really want to ruin someone’s life for the purpose of our learning goals?:) So, what’s at core? It’s about a radical reorientation. It’s about being triggered to change your worldview. Is there something that we can adapt?

The author of the paper pointed me to her co-author, who unveiled a suite of work around Transformative Experience Theory. These are smaller experiences. In one article, they cite the difference between transformative learning and transformative experiences, characterizing the latter as “smaller shifts in perspective tied to the learning of particular content ideas”. That is, scaling transformative learning down to practical use, in their case for schools. This sounds like it’s more likely to have traction for day to day work.

The core of transformative experience, however, is more oriented towards the classroom and not the workplace. To quote: “Transformative experiences occur when students take ideas outside the classroom and use them to see and experience the world in exciting new ways.” All well and good, and we do want our learners to perceive the workplace in new ways, but it’s not just presenting ideas and facilitating the slow acquisition. We need to find a handle to do this reliably and quickly.

My initial thought is about ‘surprise’. Can we do less than trigger a life-changing event, but provide some mismatch between what learners expect and what occurs to open their eyes? Can we do that systematically; reliably, and repeatedly? That’s where my thinking’s going: about ensuring there’s a mismatch because that’s the teachable moment.

Can we do small scale violations of expectations that will trigger a recognition of the need for (and willingness to accomplish) learning? My intuition says we can. What say you? Stay tuned!

Fish & Chips Economics

A colleague, after hearing my take on economics, suggested I should tell this story. It’s a bit light-hearted, but it does make a point. And I’ve expanded it here for the purposes of reading versus listening. You can use other services or products, but I’ve used fish and chips because it’s quite viscerally obvious.

A colleague, after hearing my take on economics, suggested I should tell this story. It’s a bit light-hearted, but it does make a point. And I’ve expanded it here for the purposes of reading versus listening. You can use other services or products, but I’ve used fish and chips because it’s quite viscerally obvious.

Good fish and chips are a delight. When done well, they’re crispy, light, and not soggy. Texturally, the crunch of the batter complements the flakiness of the fish as the crunchier exterior of the chips (fries, for us Yanks) complements the softness of the potato inside. Flavorwise it’s similarly a win, the battered fish a culinary combination of a lightly savory batter against the simple perfection of the fish, and the chips provide a smooth complement. Even colorwise, the light gold of the chips set against the richer gold of the fish makes an appealing platter. It’s a favorite from England to the Antipodes.

And we know how to do it. We know that having the proper temperature, and a balanced batter, and the right sized fries, are key to the perfection. There is variation, the thickness of the fries or the components of the batter, but we know the parameters. We can do this reliably and repeatably.

So why, of all things, do we still have shops that sell greasy, sodden fish and chips? You know they’re out there. Certainly consumers should avoid such places and only patronize purveyors who are able to replicate a recipe that’s widely known. Yet, it is unfortunately all too easy to wander from town to town, from suburb to suburb, and find a surprising variation. This just doesn’t make sense!

And that’s an important “doesn’t make sense”. Because, economics tells us that competition will drive a continuing increase in the quality of products and services. Consumers will seek out the optimal product, and those who can’t compete will fall away. Yet these variations have existed for decades! “Ladies & gentlemen, we have a conundrum!”

The result? The fundamental foundation of our economy is broken. (And, of course, I’m using a wee bit of exaggeration for humor.) However, I’m also making a point: we need to be careful about the base statements we hear.

The fact of the matter is that consumers aren’t optimizing, they’re ‘satisficing’. That is, consumers will choose ‘satisfactory’ solutions rather than optimal. It’s a tradeoff: go a mile or two further for good fish and chips, or just go around the corner for the less desirable version. Hey, we’re tired at the end of a long day, or the kids are on a rampage, or… This, in the organizational sense, was the basis of Herb Simon’s Nobel Prize in Economics, before he went on to be a leader of the cognitive science revolution.

The underlying point, besides making an affectionate dig at our economic model, is that the details matter. A joke is that economics predictions have no real basis in science, but then important assumptions are made regardless. This isn’t a political rant, in any case, it’s more a point about the fundamentals of society, and how we evaluate them. As requested.

Getting brainstorming wrong

There’s a time when someone takes a result, doesn’t put it into context, and leads you to bad information. And we have to call it out. In this case, someone opined about a common misconception in regards to brainstorming. This person cited a scientific study to buttress an argument about how such a process should go. However, the approach cited in the study was narrower than what brainstorming could and should be. As a consequence, the article gave what I consider to be bad information. And that’s a problem.

Brainstorming

Brainstorming, to be fair, has many interpretations. The original brought people into a room, had them generate ideas, and evaluate them. However, as I wrote elsewhere, we now have better models of brainstorming. The most important thing is to get everyone to consider the issue independently, before sharing. This taps into the benefits of diversity. You should have identified the criteria of the problem to be addressed or outcome you’re looking for.

Brainstorming, to be fair, has many interpretations. The original brought people into a room, had them generate ideas, and evaluate them. However, as I wrote elsewhere, we now have better models of brainstorming. The most important thing is to get everyone to consider the issue independently, before sharing. This taps into the benefits of diversity. You should have identified the criteria of the problem to be addressed or outcome you’re looking for.

Then, you share, and still refrain from evaluation, looking for ideas sparked from the combinations of two individual ideas, extending them (even illogically). the goal here is to ensure you explore the full space of possibilities. The point here is to diverge.

Finally, you get critical and evaluate the ideas. Your goal is to converge on one or several that you’re going to test. Here, you’re looking to surface the best option under the relevant criteria. You should be testing against the initial criteria.

Bad Advice

So, where did this other article go wrong? The premise what that the idea of ‘no bad ideas’ wasn’t valid. They cited a study where groups were given one of three instructions before addressing a problem: not to criticize, free to debate and criticize, or no instructions. The groups with instructions did better, but the criticize group were. best. And that’s ok, because this wasn’t an optimal brainstorming design.

What the group with debate and criticizing were actually tasked with doing most of the whole process: freewheeling debate and evaluation, diverging and converging. The second instruction group was just diverging. But, if you’re doing it all at once, you’re not getting the benefit of each stage! They were all missing the independent step, the freewheeling didn’t have evaluation, and the combined freewheeling and criticizing group wouldn’t get the best of either.

This simplistic interpretation of the research misses the nuances of brainstorming, and ends up giving bad advice. Ok, if the folks doing the brainstorming in orgs are violating the premise of the stages, it is good advice, but why would you do suboptimal brainstorming? It might take a tiny bit longer, but it’s not a big issue, and the outputs are likely to be better.

Doing better

We can, and should, recognize the right context to begin with, and interpret research in that context. Taking an under-informed view can lead you to misinterpret research, and consequently lead you to bad prescriptions. I’m sure this article gave this person and, by association, the patina of knowing what they’re talking about. They’re citing research, after all! But if you unpack it, the veneer falls off and it’s unhelpful at the core. And it’s important to be able to dig deep enough to really know what’s going on.

I implore you to turn a jaundiced eye to information that doesn’t come from someone with some real time in the trenches. We need good research translators. I’ve a list of trustworthy sources on the resources page of my book on myths. Tread carefully in the world of self-promoting media, and you’ll be less hampered by the mud ;).

What’s the CEO want to see

This issue came up recently, and it’s worth a think. What would a CEO hope to see from L&D? And I think this is in two major areas. The first is for optimum execution, and the other is for continual innovation. It’s easier to talk about the former, so we’ll start there. However, if (or, rather, when ;) L&D starts executing on the other half, we should be looking for tangible outcomes there too.

Optimal Execution

To start with, we need specific responses for the things an organization knows they need to do (until that can be automated? Orgs must do what matters, and address any gaps. Should our glorious leader care about us doing what we’re supposed to? No. Instead, this individual is concerned with gaps that have emerged and that they’re fixed. Of course, we have to admit problems we’re having as well.

The CEO shouldn’t have to care how efficient we are. That’s a given! Sure, when requested, we must be able to demonstrate that our costs were covered by the benefits of the change. But the fact that we’re no more expensive than anyone else per seat per hour is just assumed! If we’re asked, we should be able to show that, and it can be in a written report. However, mentioning efficiency in the C-suite is a ticket out.

What a CEO (should) care about are any performance gaps that have arisen in previous meetings and the changes that L&D has achieved. You know, “we’ve been able to decrease those troubling call handling times back down to x.5 minutes” or “we identified the problem and were able to reduce the errors in manufacturing back to our y/100 baseline” These may even include “saving us $z”.

To do this, of course, means you’re actually addressing key business impact drivers. You need to be talking to the business units, using their measures and performance consulting to find and fix the problems. It’s not “ok, we’ll get you a course on this”, it’s “sure, we can do that course, and tell me what the outcome should be, how will we know it worked?”

Yes, particularly at the beginning when you’re establishing credibility, you may be asked for ROI. How much did it cost to fix this. You do want the fix to cost less than the problem. But that won’t be the main criteria. The CEO should be focusing on strategy, and fixing problems that prevent being able to execute on those directions.

Continual Innovation

That strategy, of course, comes from new ideas. And, to be fair, so too due the fixes to problems. That’s the learning that occurs outside the course! Research, innovation, design, trouble-shooting, all these start with a question and ultimately an answer will be learned. It comes from experimentation and reflection, as well as looking at what others’ have done (inside and out).

What are the. measures here? Well, if we take the result that innovation comes from collective constructive friction instead of the individual brainstorm, then meaningful social media activity would be one indicator. Increasing either the quantity of quality discussions would be one. Just ‘activity’ in the social systems has been one initial measure. But we can go further.

We should expect the impact of these activities to impact particular outcomes. If it’s in sales, we should see more proposals generated, higher success rates, lower closing times, lower closing costs, and other such metrics. In operations, we might see fewer errors, more experiments, more new product ideas generated. And so on. E.g. “we increased the percentage of…” The point is that if people are sharing lessons learned, we should see faster learning and higher success rates and/or greater innovations.

Of course, we have to count these. Whatever method, whether xAPI or proprietary, we should be tracking activity and correlating with business metrics. With a little thought, we can be looking for and leveraging interesting relationships between what people do in learning (and performing) and what the outcomes are.

We could also be reporting out on the outputs of sessions that L&D facilitates. At least, initially, and then the overall increase in innovation metrics would be appropriate. The key role of L&D in innovation is developing capabilities around best principles, and that includes facilitating and developing facilitative skills.

Impact

The take-home is that the CEO shouldn’t want to hear our internal metrics on effectiveness and efficiency. Don’t expect that person to know about learning theory, best approaches, nor L&D benchmarks. They want, and need, organizational impact. Even the number of or percentage of employees who’ve taken L&D services isn’t enough. What has that done? Report impact on the organization. Let the CEO know how much you’ve helped the key metrics, which are directly tied to the bottom line. Yes, you have to start working with business partners. Yes, it requires breaking some molds. But ultimately, L&D will live, or die, by whether they’re accountable to, and contributing to, organizational success in demonstrable ways.

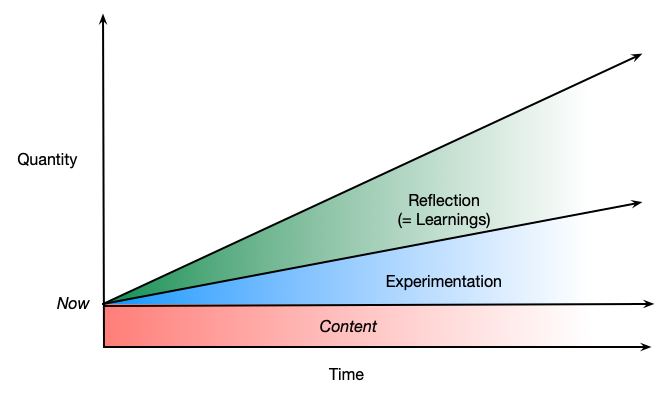

Learning from Experimentation

At the recent LearnTec conference, I was on a panel with my ITA colleagues, Jane Hart, Harold Jarche, and Charles Jennings. We were talking about how to lift the game of Modern Workplace Learning, and each had staked out a position, from human performance consulting to social/informal. Mine (of course :) was at the far end, innovation. Jane talked about how you had to walk the walk: working out loud, personal learning, coaching, etc. It triggered a thought for me about innovating, and that meant experimentation. And it also occurred to me that it led to learning as well, and drove you to find new content. Of course I diagrammed the relationship in a quick sketch. I’ve re-rendered it here to talk about how learning from experimentation is also a critical component of workplace learning.

The starting point is experimentation. I put in ‘now’, because that’s of course when you start. Experimentation means deciding to try new things, but not just any things. They should be things that would have a likelihood of improving outcomes if they work. The goal is ‘smart’ experiments, ones that are appropriate for the audience, build upon existing work, and are buttressed by principle. They may or may not be things that have worked elsewhere, but if so, they should have good outcomes (or, more unlikely, didn’t but have a environmentally-sound reason to work for you).

The starting point is experimentation. I put in ‘now’, because that’s of course when you start. Experimentation means deciding to try new things, but not just any things. They should be things that would have a likelihood of improving outcomes if they work. The goal is ‘smart’ experiments, ones that are appropriate for the audience, build upon existing work, and are buttressed by principle. They may or may not be things that have worked elsewhere, but if so, they should have good outcomes (or, more unlikely, didn’t but have a environmentally-sound reason to work for you).

Failure has to be ok. Some experiments should not work. In fact, a failure rate above zero is important, perhaps as much as 60%! If you can’t fail, you’re not really experimenting, and the psychological safety isn’t there along with the accountability. You learn from failures as well as from successes, so it’s important to expect them. In fact, celebrate the lesson learned, regardless of success!

The reflections from this experimentation take some thought as well. You should have designed the experiments to answer a question, and the experimental design should have been appropriate (an A-B study, or comparing to baseline, or…). Thus, the lesson extracted from learning from experimentation is quickly discerned. You also need to have time to extract the lesson! The learnings here move the organization forward. Experimentation is the bedrock of a learning organization, if you consolidate the learnings. One of the key elements of Jane’s point, and others, was that you need to develop this practice of experimentation for your team. Then, when understood and underway, you can start expanding. First with willing (ideally, eager) partners, and then more broadly.

Not wanting to minimize, nor overly emphasize, the role of ‘content’, I put it in as well. The point is that in doing the experimentation, you’re likely to be driven to do some research. It could be papers, articles, blog posts, videos, podcasts, webinars, what have you. Your circumstances and interests and… who knows, maybe even courses! It includes social interactions as well. The point is that it’s part of the learning.

What’s not in the diagram, but is important, is sharing the learnings. First, of course, is sharing within the organization. You may have a community of practice or a mailing list that is appropriate. That builds the culture. After that, there’s beyond the org. If they’re proprietary, naturally you can’t. However, consider sharing an anonymized version in a local chapter meeting and/or if it’s significant enough or you get good enough feedback, go out to the field. Present at a conference, for instance!

Experimentation is critical to innovation. And innovation takes a learning organization. This includes a culture where mistakes are expected, there’s time for reflection, practices for experimentation are developed, and more. Yet the benefits to create an agile organization are essential. Experimentation needs to be part of your toolkit. So get to it!