I’ve been wrong before, and I’ll be wrong again, and that’s ok <warning: link is NSFW>. It’s like with science: if you change your mind, you weren’t lying before, you’ve learned more now. So I’ve been wrong about the emphasis between practice and examples. What I’ve learned is that, in general, practice isn’t the only area of importance, and the benefits of examples before practice.

So, as part of the Learning Development Accelerator‘s YOK (You Oughta Know) series, I got the chance to interview John Sweller. I’ve known John, I’m very honored to say, from my days at UNSW. I was aware of his reputation as a cog sci luminary, but he also turned out to be a really nice person. He’s the originator of Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), and he was kind enough to agree to talk about it.

As background, he’s tapped into David Geary’s biologically primary and biologically secondary learning. The core idea is that some things we’ve evolved to learn, like speaking. Then there are things we’ve developed intellectually, like reading and writing, that aren’t natural. Instruction is to assist us to acquire the latter. The latter typically has high ‘element interactivity’, whereby there are complex interrelationships to master. That is, it’s complex.

CLT posits that we have limited cognitive capacity, and overwhelming that capacity interferes with learning. The model talks about two types of load. The first is intrinsic load, that implied by the learning task. The second is extrinsic load, coming from additional factors in the particular situation. The premise is that learning complex things (biologically secondary) has such a high intrinsic load that we really need to focus on managing load so we can gradually acquire the entailed relationships.

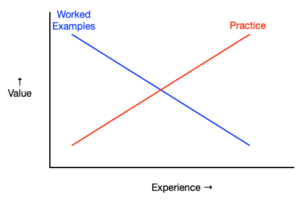

There are a number of implications of CLT, but one is about the value of worked examples. An important element is showing the thinking behind the steps. A second empirical result is that worked examples are better than practice! At least, initially, for novices. Yet this upends one of my recommendations, which is generally that the most important thing we can do to improve our learning is focus on better practice. I still believe that, but now with the caveat after worked examples.

There are a number of implications of CLT, but one is about the value of worked examples. An important element is showing the thinking behind the steps. A second empirical result is that worked examples are better than practice! At least, initially, for novices. Yet this upends one of my recommendations, which is generally that the most important thing we can do to improve our learning is focus on better practice. I still believe that, but now with the caveat after worked examples.

Now, he didn’t tell us when that happens, e.g. when you switch from worked examples to practice. However, like the answer to how much spacing needed for the spaced practice effect, I suspect the answer is ‘it depends’. There’s the ‘expertise reversal’ effect that says as you gain experience, the value of worked examples falls and the value of practice raises. That point, I’d suggest, is dependent on the prior knowledge of the learners, the complexity of the material, the scope, and more.

I’m now recommending, particularly for new material, that improving the learning outcomes includes meaningful practice after quality worked examples. That’s my new, better, understanding. Make sense?

As an aside, I talked about CLT in my most recent book, on learning science, with a diagram. In it, I only included intrinsic and extrinsic, as those two seemed critical, yet the classic theory also includes germane intrinsic load. One of the audience members asked him about that, and John opined that he probably needn’t have included germane. Vindication!

I was only discussing CLT and worked examples with a friend last week. Both our kids are about to start taking driving lessons. Both are total novices. One will be doing their lessons in the USA in an automatic car. The other in Great Britain, in a manual (stick-shift, I believe is the American colloquialism) car.

It appears, learning to drive a manual car over an automatic requires a lot more explanation and worked examples while the car is stationary, compared to an automatic car. In an automatic car, I am lead to believe, you can pretty much start with practice.

It might be a simple but interesting topic to research. A sample of novices in automatic cars compared to a sample of novices in manual cars.

As I think about it more, for complex topics there may well be cycles of examples and practice. You might need to master one set of relationships before you complicate it with more. For example, you might first master subtraction, and borrowing, each with worked examples and practice. Then you’d be ready to go on to multi-column subtraction, again with examples and practice..

I’ve come back to this article from the ‘Exposing myself’ article published yesterday. For clarity; where might I find a definition of what is a ‘Worked Example’, that distinguishes it from ‘Practice’. Thanks.

Peter, I refer you to the Wikipedia entry, which defines worked examples: “step-by-step demonstration of how to perform a task or how to solve a problem”. That is, the practice is performed for you, rather than you having to do it. See the section on expertise reversal, too, where the benefit of worked examples tends to go away as your expertise increases.