Businesses are composed of core functions, and they optimize them to succeed. In areas like finance, operations, and information technology, they prioritize investments, and look for continual improvement. But, with the shift in the competitive landscape, there‘s a gap that’s being missed. And I‘m wondering if a focus on cognitive science needs to be foregrounded.

In the old days, most people were cogs in the machine. They weren‘t counted on to be thinking, but instead a few were thinking for the many. And those who could do so were selected on that basis. But that world is gone.

Increasingly, anything that can be automated should be automated. The differentiators for organizations are no longer on the execution of the obvious, but instead the new advantage is the ability to outthink the competition. Innovation is the new watchword. People are becoming the competitive advantage.

However, most organizations aren‘t working in alignment with this new reality. Despite mantras like ‘human capital management’ or ‘talent development’, too many practices are in play that are contrary to what‘s known about getting the best from people. Outdated views like putting information into the head, squelching discussion, and avoiding mistakes are rife. And the solutions we apply are simplistic.

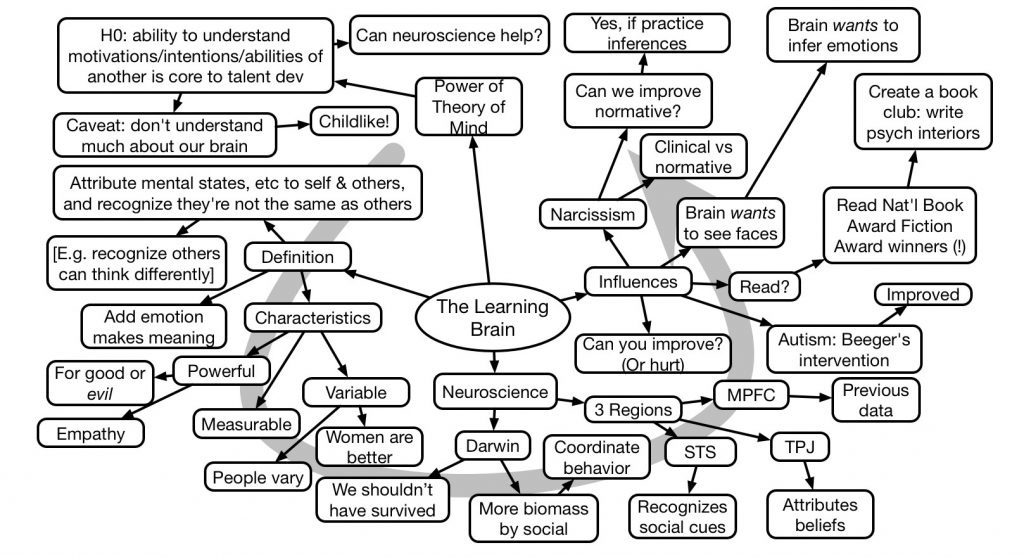

Ok, so neuroscientist John Medina says our understanding of the brain is ‘childlike‘. Regardless, we have considerable empirical evidence and conceptual frameworks that give us excellent advice about things like distributed, situated, and social cognition. We know about our mistakes in reasoning, and approaches to avoid making mistakes. Yet we‘re not seeing these in practice!

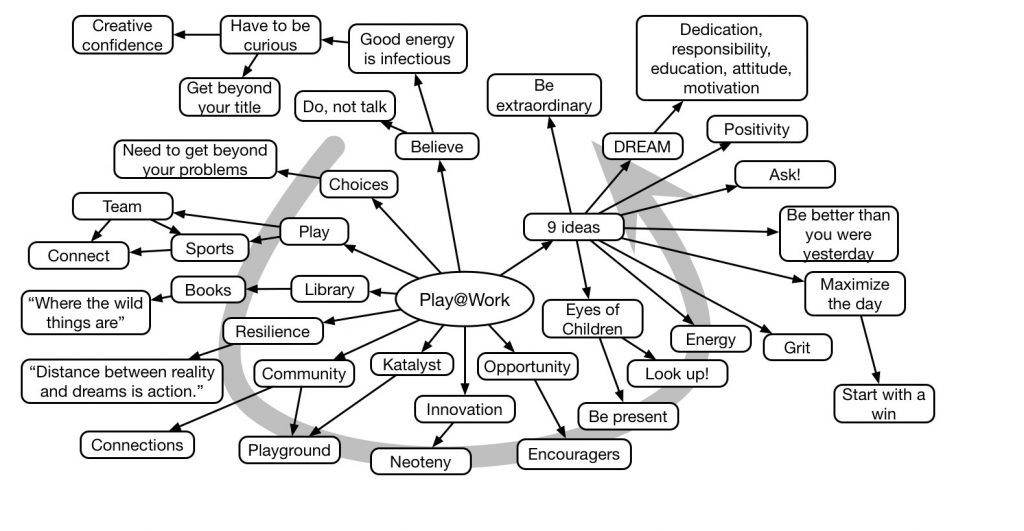

What I‘m suggesting is a new focus. A new area of expertise to complement technology, business nous, financial smarts, and more. That area is cognitive expertise. Here I’m talking about someone with organizational responsibility, and authority, to work on aligning practices and processes with what‘s known about how we think, work, and learn. A colleague suggested that L&D might make more sense in operations than in HR, but this goes further. And, I suggest, is the natural culmination of that thought.

So I‘m calling for a Chief Cognitive Officer. Someone who‘s responsibility ranges from aligning tools (read: UI/UX) with how we work, through designing continual learning experiences, to leveraging collective intelligence to support innovation and informal learning. Doing these effectively are all linked to an understanding of how our brains operate, and having it distributed isn‘t working. The other problem is that not having it coordinated means it‘s idiosyncratic at best.

One problem is that there‘s too little of cognitive awareness anywhere in the organization. Where does it belong? The people closest are (or should be) the L&D (P&D) people. If not, what’s their role going to be? Someone needs to own this.

Digital transformation is needed, but to do so without understanding the other half of the equation is sort of like using AI on top of bad data; you still get bad outcomes. It’s time to do better. It’s a radical reorg, but is it a necessary change? Obviously, I think it is. What do you think?