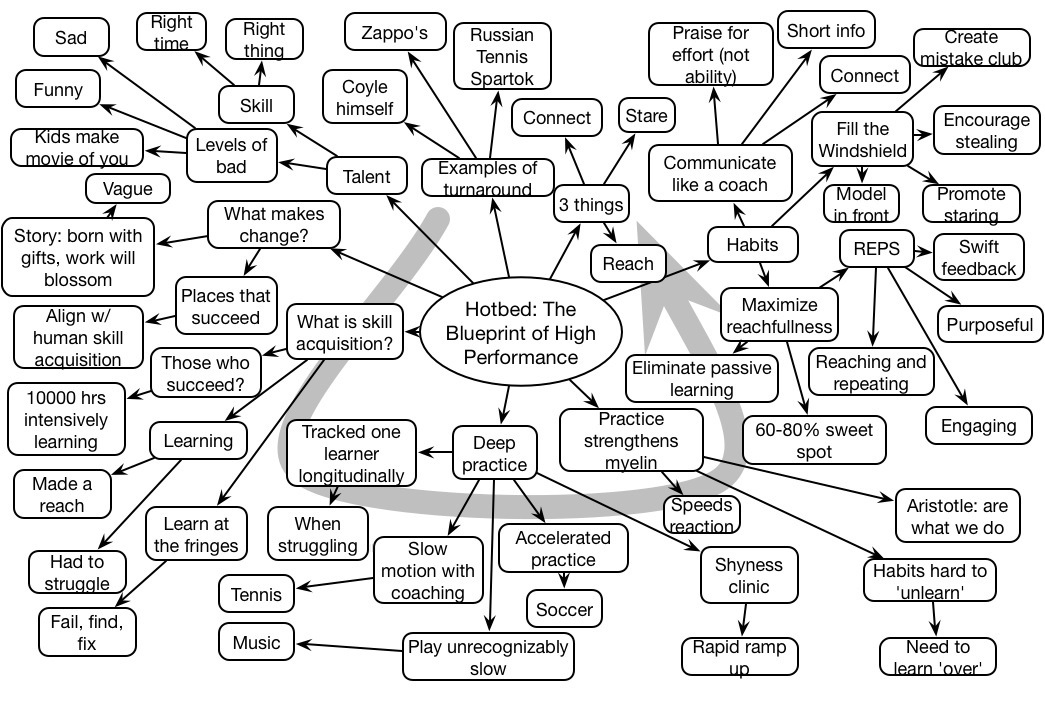

Daniel Coyle gave a wonderfully funny, passionate, and poignant keynote, talking about what leads to top performance. Naturally, I was thrilled to hear him tout the principles that I suggest make games such a powerful learning environment: challenge, tight feedback, and large amounts of engaging practice. With compelling stories to illustrate his points, he balanced humor and emotional impact to sell a powerful plea for better learning.

Barrier to scale?

I was part of a meeting about online learning for an institution, and something became clear to me. We were discussing MOOCs (naturally, isn’t everyone?), and the opportunities for delivering quality learning online. And that’s where I saw a conflict that suggested a fundamental barrier to scale.

When I think about quality learning, the core of it is, to me, about the learning activity or experience. And that means meaningful problems with challenge and relevance, more closely resembling those found in the real world than ones typically taught in schools and training. There’s more.

The xMOOCs that I’ve seen have a good focus on quality assessment aligned to the learning goal, but there’s a caveat. Their learning goals have largely been about cognitive skills, about how to ‘do’. And I’m a big fan of focusing on ‘do’, not know. But I recognize there’s more, there’s to ‘be’. That is, even if you have acquired skills in something like AI programming, that doesn’t mean you’re ready to be employed as an AI programmer. There’s much more. For instance, how to keep yourself up to date, how to work well with others, what are the nature of AI projects, etc.

It also came up that when polled, a learned committee suggested top things to learn were to lead, to work well on a team, communicate, etc. These are almost never developed by working on abstract problems. In fact, I’d suggest that the best activities are meaningful, challenging, and collaborative. The power of social learning, of working together to receive other viewpoints and negotiate a shared understanding, and creating a unique response to the challenge, is arguably the best way to learn.

Consequently, it occurs to me, that you simply cannot make a quality learning experience that can be auto-assessed. It needs to be rich, and mentored, scaffolded, and evaluated. Which means that you have real trouble scaling a quality learning experience. Even with peer assessment, there’s some need for human intervention with every group’s process and product. Let alone generating the beneficial meta-learning aspects that could come from this.

So, while there are real values to be developed from MOOCs, like developing perhaps some foundation knowledge and skills, ultimately a valuable education will have to incorporate some mechanism to handle meaningful activities to develop the desirable deep understanding. A tiered model, perhaps? This is still embryonic, but it seems to me that this is a necessary step on the way to a real education in a domain.

Leaving Trails

So I was away for the weekend at a retreat with like-minded souls, Up to All of Us, thinking deeply about the issues that concern us. I walked away with some new and renewed friendships, relaxed, and with a few new thoughts. Two memes stuck with me, and the first was “leaving trails”.

For context, the event featured designers – graphic, industrial, visual – but mostly learning designers. In a session on supporting the growth of design awareness, we were being led through an exercise on body-storming (using role plays to work through issues), and one of the elements that surfaced was posting your designs on the walls in places where it’s hard to see others’ work. And I had two reactions to this, the first being that the ability to share work was a culture issue, but the other was a transparency issue.

The point that I brought up was that just seeing the work wasn’t enough, ideally you’d want to understand what was the thinking behind it (not just working out loud, but thinking out loud). That can come from a conversation around the work, but that’s not always possible (particularly if it’s a virtual wall).

And I thought the leader of the exercise, an eloquent and experienced designer, said that you couldn’t really annotate your thoughts about the work. Which I fundamentally disagreed with, but he then went on to talk about showing interim work, specs, etc (and I’m filling in here with some inferences because memory’s not perfect).

What emerged in my thinking was the phrase leaving trails, not just your work, but the trajectories, constraints, and more. As I’ve argued before, I think showing the thinking behind decisions is going to be increasingly important at every level. At workgroup level, individuals will be better able to collaborate if their (prior) work is detailed. Communities of practice similarly need such evidence. Another colleague also presented work on B Corps, benefit corporations, in which businesses will move from shareholder returns to missions, and such transparency will be necessary here as well as for eGovernment. I reckon, what with ClueTrain, any org that isn’t being transparent enough will lose trust.

Of course, the comfort level in sharing gets back to the culture issue: people have to be safe to share their work and give and receive feedback in constructive ways to move forward. Which is really the subject of the next meme.

(NB: one of the principles of the event is Chatham House Rule, which basically says you can’t share personal details without prior approval, and I didn’t ask, so the perpetrators and victims shall remain nameless.)

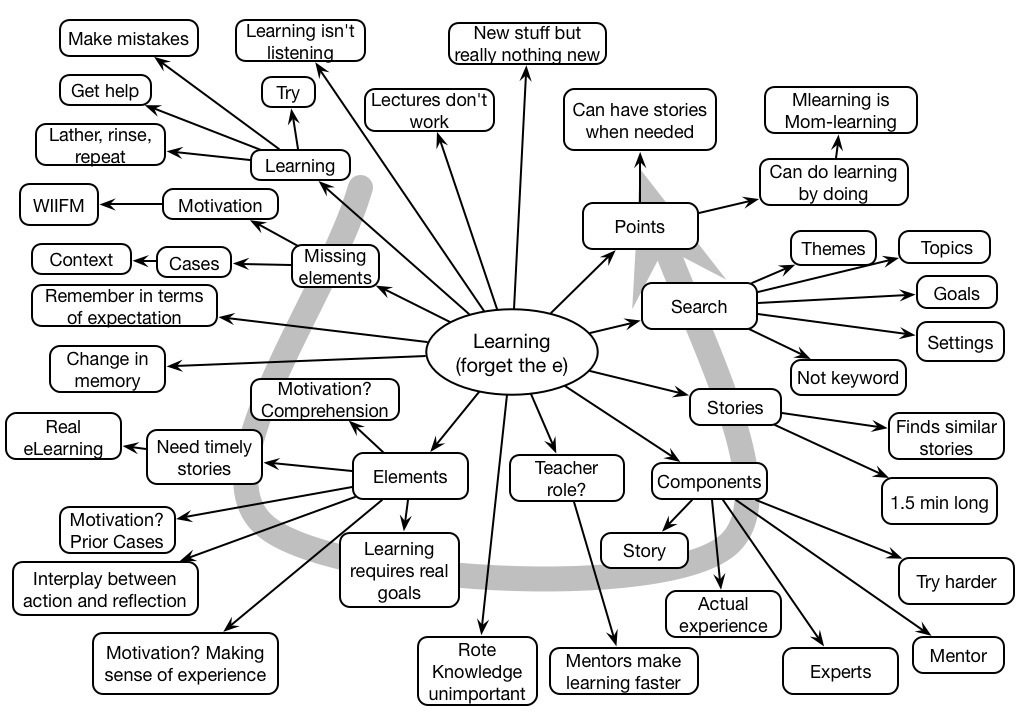

Roger Schank #eli3 Keynote Mindmap

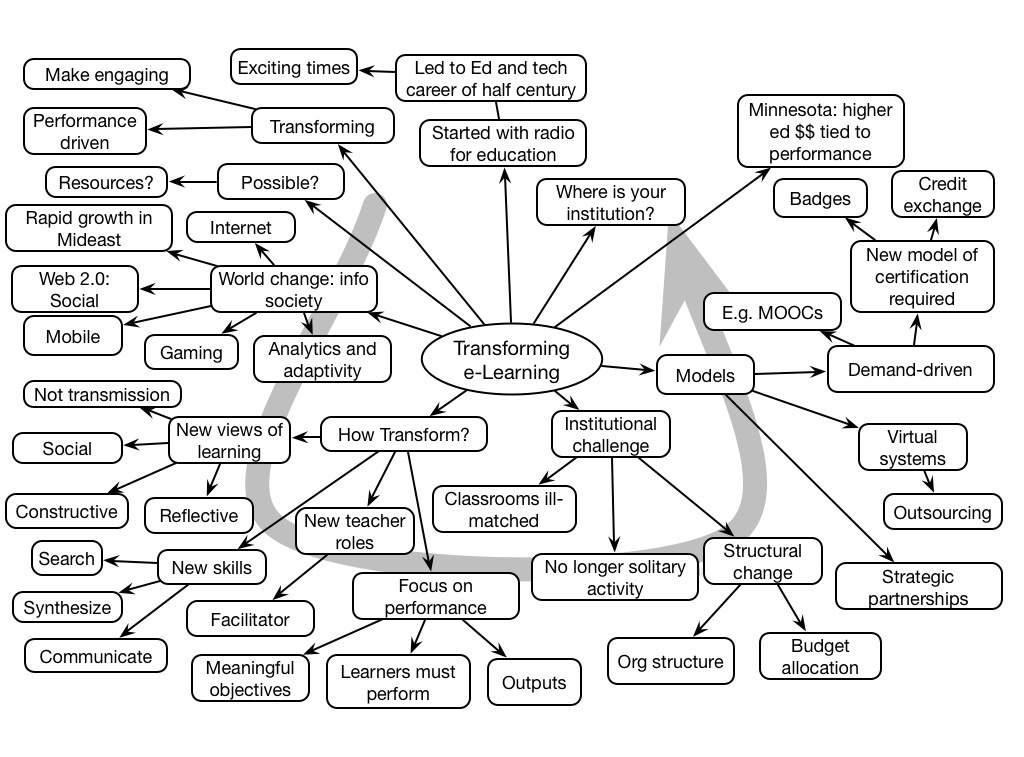

Michael Moore #eli3 Keynote Mindmap

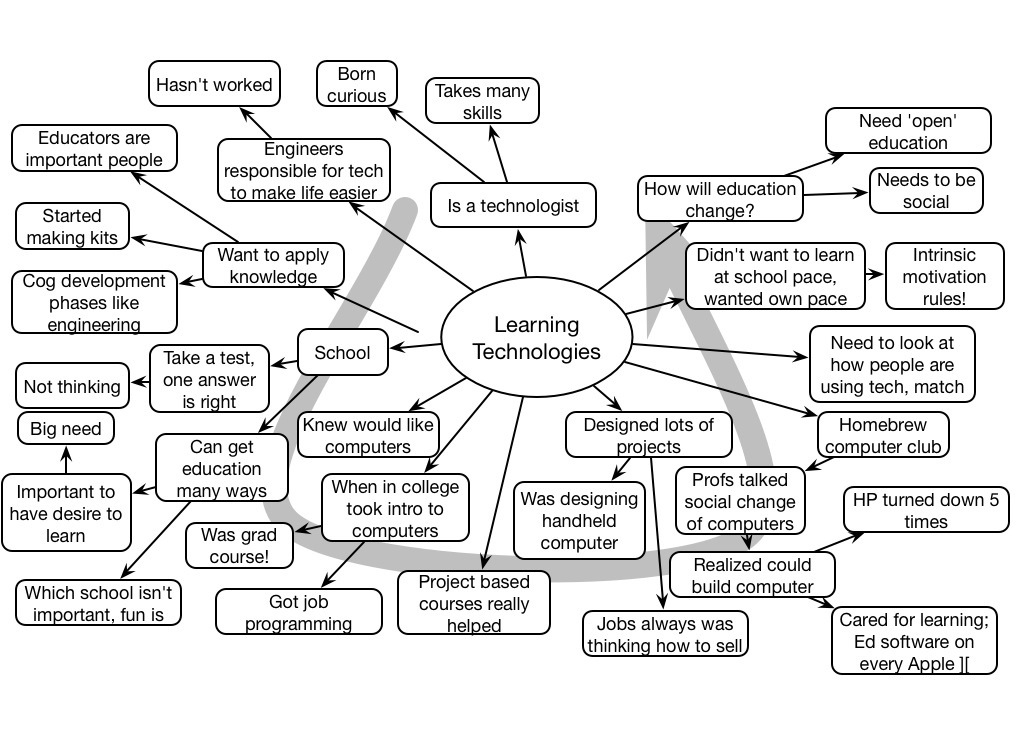

Steve Wozniak #eli3 Keynote Mindmap

The legendary Steve “The Woz” Wozniak was the opening keynote at the 3rd International Conference of e-Learning and Distance Learning. In a wide-ranging, engaging, and personal speech, Steve made a powerful plea for the value of the thoughtful learner and intrinsic motivation, project-based learning, social, and self-paced learning.

Unlearning?

Recently, there’s been a lot of talk and excitement about unlearning, and it’s always rubbed me the wrong way. Because, frankly, unlearning physiologically isn’t really an option. So I thought I’d talk about the cognitive processes, and then look at what folks are talking about.

Learning has been cutely characterized as “neurons that fire together, wire together”. And that’s really it: learning is about strengthening associations between patterns (which is why you can only learn so much at one time and then need to sleep, that strengthening effect only takes so much at one shot). We start with conscious effort and compile it down below conscious level.

However, you can’t really weaken those associations! So, you simply can’t unlearn. What really happens, as Dr. Jane Bozarth suggests, is: “overwriting existing knowledge or skill, or just pushing it to the background to accommodate something new, or rewiring pathways”. And points out that it’s hard work.

In short, unlearning is really relearning. And it’s harder because you need to overcome prior experience, strengthen the associations of the new beyond the existing strength of the old. And it’s important that, if things have changed, or previous experience or instinct will lead you elsewhere, you need to make sure that you’ve now got learners making the decisions in the effective ways. Which may mean modifying, not necessarily just replacing, but it does take conscious effort in analysis and design, diagnosing misconceptions, figuring appropriate levels of practice, etc.

So why this excitement about unlearning? It appears people are having fun with words. They’re using the phrase to mean something else. Take, for instance, this definition:

“Unlearning is not exactly letting go of our knowledge or perceptions, but rather stepping outside our perceptions to stand apart from our world views and open up new lenses to interpret and learn about the world.” – Erica Dhawan

Um, okay. The same article quotes Prasad Kaipa as saying “we generate anew rather than reformulate the same old stuff”. So, it’s about a different perspective. That’s valuable. Why call it unlearning then? It could be a step to unlearning, looking afresh and seeing new opportunities for different ways of doing things, but it’s not really unlearning.

So I see no reason to mislead people. Learning is rewarding, and touting things as unlearning make it seem as straightforward as learning, but relearning a new way is harder. The use of the term seems to minimize the effort required. And using the term to mean something else seems misleading. If you want to talk about shifting perspectives, do so!

What am I missing? Until I find a better explanation than what I’ve found, I’m calling out the term. Genially, of course.

Compounding Intelligence

It is increasingly evident that as we unpack how we get the best results from thinking, we don’t do it alone. Moreover, the elements that contribute emphasize diversity. Two synergistic events highlight this.

First, my colleague Harold Jarche has an interesting post riffing off of Stephen Johnson’s new book, Future Perfect. In looking at patterns that promote more effective decision making, an experiment is cited. In that study, a diverse group of lower intelligence produces better outputs than a group of relatively homogenous smart folks. They quote Scott Page, saying “Diversity trumps ability”. Hear hear.

This resonated particularly in light of an article I discovered last week that talked about Tom Malone’s work on looking at what he calls “collective intelligence“. In it, Tom says “Our future as a species may depend on our ability to use our global collective intelligence to make choices that are not just smart, but also wise.” I couldn’t agree more, and am very interested in the wisdom part. Of interest in the article is a series of studies he did looking at what led to better outputs from groups, and they debunked a number of obvious factors including the above issue of intelligence. Two compelling features were the social perceptiveness of the group, e.g. how well they tuned in to what other members of the group thought, and how even the turn-taking was. The more everyone had an equal chance to talk (instead of a one-sided conversation), and the more socially aware the group, the better the output. Interestingly, which he correlated to the socially aware, was that the more women the better!

The point being that learning social skills, using good meeting processes, and emphasizing diversity, all actions similar to those needed for effective learning organizations, lead to better decision making. If you want good decisions, you need to break down hierarchies, open up the conversation channels, and listen. We have good science about practices that lead to effective outcomes for organizations. Are you practicing them?

Vale David Jonassen

David Jonassen passed away on Sunday. He had not only a big impact on the field of computers for learning, but also on learning itself. And he was a truly nice person.

I had early on been a fan of his work, his writing on computers as cognitive tools was insightful. He resisted the notion of teaching computing, and instead saw computers as mind tools, enablers of thinking. He was widely and rightly regarded as an influential innovator for this work.

I also regularly lauded his work on problem-solving. The one notion that really resonated was that the problems we give to kids in schools (and too often to adults in training) bear little resemblance to the problems they’ll face outside. He did deep work on problem-solving that more should pay attention to. He demonstrated that you could get almost as good a performance on standard tests using meaningful problems, and you got much better results on problem-solving skills (21st century skills) as well. I continue to apply his principles in my learning design strategies.

I had the opportunity to meet him face to face at a conference on learning in organizations. While I was rapt in his presentation, somehow it didn’t work for the audience as a whole, a shame. Still, I had the opportunity to finally talk to him, and it was a real pleasure. He was humble, thoughtful, and really willing to engage. I subsequently shared a stage with him when he presented virtually to a conference I was at live, and was thrilled to have him mention he was using my game design book in one of his classes.

He contributed greatly to my understanding, and to the field as a whole. He will be missed.

Designing Backward and Forward

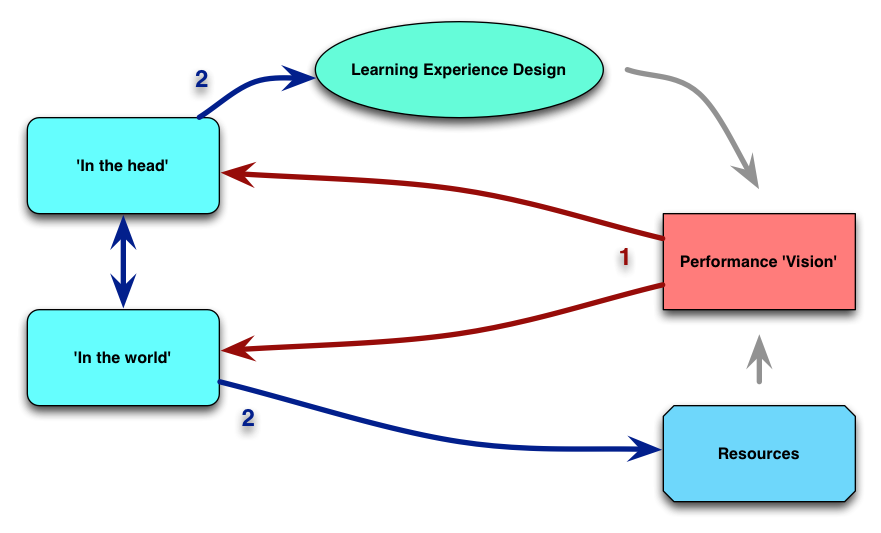

At the recent DevLearn, several of us gathered together in a Junto to talk about issues we felt were becoming important for our field. After a mobile learning panel I realized that, just as mlearning makes it too easy to think about ‘courses on a phone’, I worry that ‘learning experience design’ (a term I’ve championed) may keep us focused on courses rather than exploring the full range of options including performance support and eCommunity.

So I began thinking about performance experience design as a way to keep us focused on designing solutions to performance needs in the organization. It’s not just about what’s in our heads, but as we realize that our brains are good at certain things and not others, we need to think about a distributed cognition solution, looking at how resources can be ‘in the world’ as well as in others’ heads.

The next morning in the shower (a great place for thinking :), it occurred to me that what is needed is a design process before we start designing the solution. To complement Kahnemann’s Thinking Fast and Slow (an inspiration for my thoughts on designing for how we really think and learn), I thought of designing backward and forward. Let me try to make that concrete.

What I’m talking about is starting with a vision of what performance would look like in an ideal world, working backward to what can be in the world, and what needs to be in the head. We want to minimize the latter. I want to respect our humanity in a way, allowing us to (choose to) do the things we do well, and letting technology take on the things we don’t want to do.

What I’m talking about is starting with a vision of what performance would look like in an ideal world, working backward to what can be in the world, and what needs to be in the head. We want to minimize the latter. I want to respect our humanity in a way, allowing us to (choose to) do the things we do well, and letting technology take on the things we don’t want to do.

In my mind, the focus should be on what decisions learners should be making at this point, not what rote things we’re expecting them to do. If it’s rote, we’re liable to be bad at it. Give us checklists, or automate it!

From there, we can design forward to create those resources, or make them accessible (e.g. if they’re people). And we can design the ‘in the head’ experience as well, and now’s the time for learning experience design, with a focus on developing our ability to make those decisions, and where to find the resources when we need them. The goal is to end up designing a full performance solution where we think about the humans in context, not as merely a thinking box.

It naturally includes design that still reflects my view about activity-centered learning (which I’m increasingly convinced is grounded in cognitive research). Engaging emotion, distributed across platforms and time, using a richer suite of tools than just content delivery and tests. And it will require using something like Michael Allen’s Successive Approximation Model perhaps, recognizing the need to iterate.

I wanted to term this performance experience design, and then as several members workshopped this with me, I thought we should just call it performance design (at least externally, to stakeholders not in our field, we can call it performance experience design for ourselves). And we can talk about learning experience design within this, as well as information design, and social networks, and…

It’s really not much more than what HPT would involve, e.g. the prior consideration of what the problem is, but it’s very focused on reducing what’s in the head, including emotion in the learning when it’s developed, using social resources as well as performance support, etc. I think this has the opportunity to help us focus more broadly in our solution space, make us more relevant to the organization, and scaffold us past many of our typical limitations in approach. What do you think?