It’s clear that our brains aren’t the logical problem-solvers we’d like to be. The evidence on our different thinking systems makes clear that we use intuition when we can, and hard thinking when we must. Except that we use intuition even when we shouldn’t, and hard thinking is very susceptible to problems. Yet we need to have reliably good outcomes to solving problems or accomplishing tasks. What can we do?

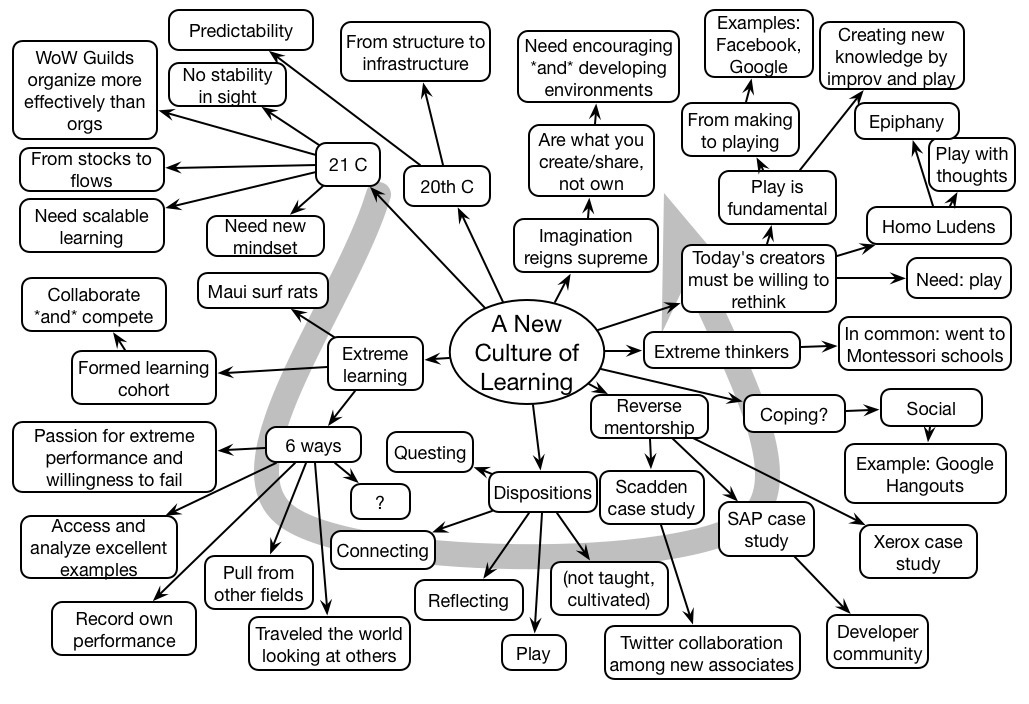

The answer, of course, is to use technology to fill in the gaps, when we can. We can automate it if we totally understand it, but the best solution is to let technology (and design) do what it can, and let our brains fill in what we do best. So, when there’s a problem or task that needs to be accomplished, and it requires some decision making, we should be doing several things.

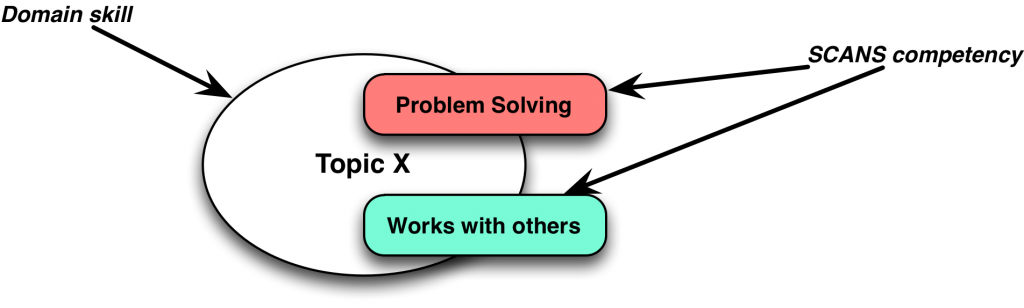

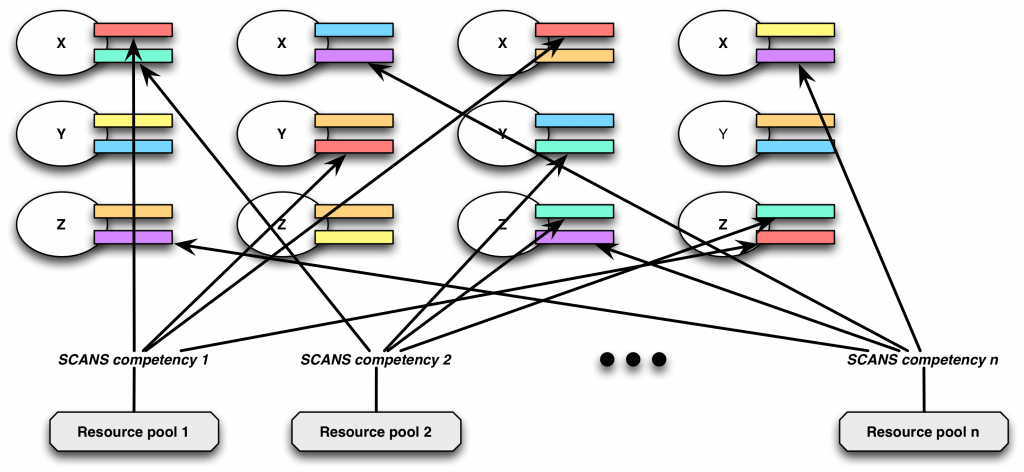

To start, we should be looking at the scope of possible situations, and determine what’s required. We should then figure out what information can be in the world (whether a resource or in other’s heads), and what has to be in the performer’s repertoire. We want to design a solution system, not just a course.

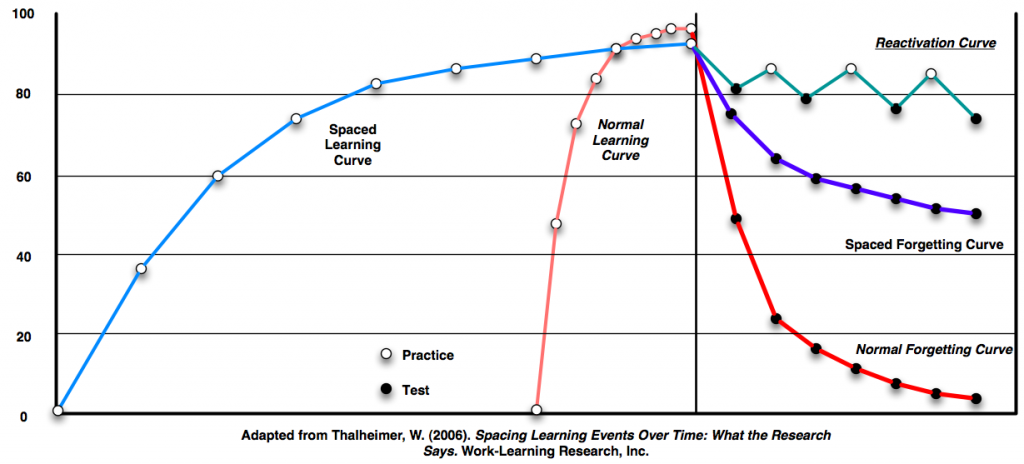

Recognize that getting things into human heads reliably is problematic at best. It takes considerable work to develop that expert intuition: considerable practice at least. So the preference should be to design either a really good support system that helps in characterization of the problem, and a dialog that helps determine what of the possible solutions matches up with the situation.

It can just be information in the world, such as a job aid or checklist, or an interactive decision support tool. Or, it could be a social network of resources such as tools and videos created by others that’s usefully searchable and the ability to ask questions of the community and get responses. It’s likely a probabilistic decision here: what is the likelihood that the network has the answer, versus what’s the possibility that we can design support that will cover the range of problems to be faced?

The point is that support design is a necessary and very viable component of performance solutions, and one that isn’t being used enough. I’m looking forward to the upcoming eLearning Guild’s Performance Support Symposium in Boston as a way to learn more, and hope to see you there!