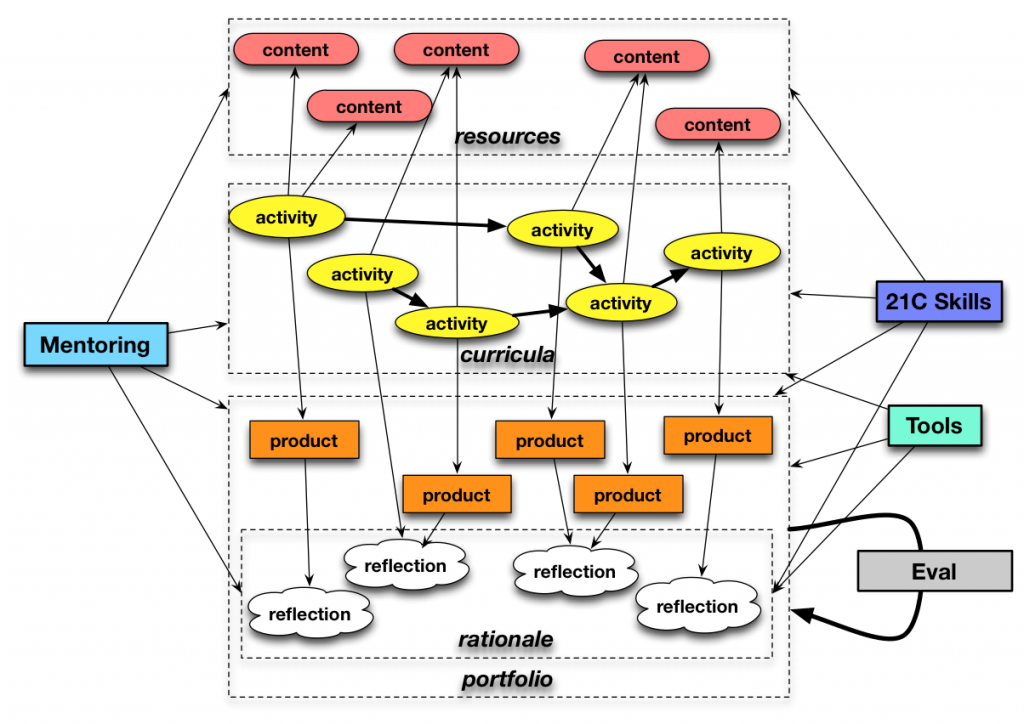

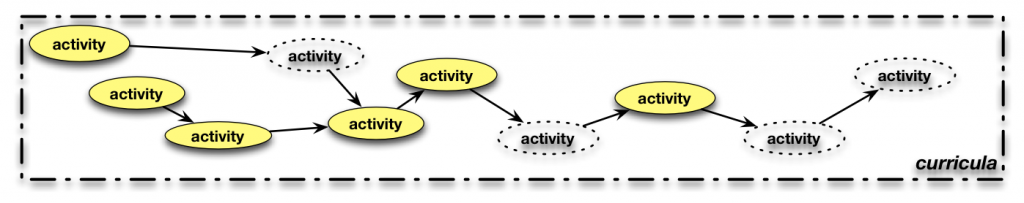

In a previous post I laid out the initial framework for rethinking learning design, and in a subsequent post I elaborated the activity component. I want to elaborate the rest a wee bit here. Two additional components of the model around the activities were content and then products coupled with reflection.

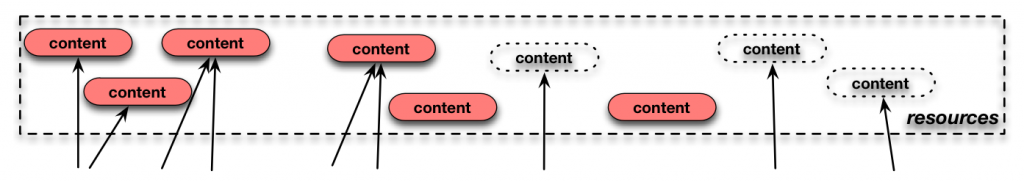

One of the driving points behind the model was to move away from content-driven learning, and start focusing on learning experience. As a consequence, the activities were central, but content was there to be driven to from the activities. So, the activity would both motivate and contextualize the need to comprehend some concept or to access an example, and then there would be access paths to the content within the activity. Or not, in that there might be a selection of content, or even the opportunity or need for the learner to choose relevant content. As with the activity, you gradually want to release responsibility to the learner for selecting content, initially modeling and increasingly devolving the locus of control.

One of the driving points behind the model was to move away from content-driven learning, and start focusing on learning experience. As a consequence, the activities were central, but content was there to be driven to from the activities. So, the activity would both motivate and contextualize the need to comprehend some concept or to access an example, and then there would be access paths to the content within the activity. Or not, in that there might be a selection of content, or even the opportunity or need for the learner to choose relevant content. As with the activity, you gradually want to release responsibility to the learner for selecting content, initially modeling and increasingly devolving the locus of control.

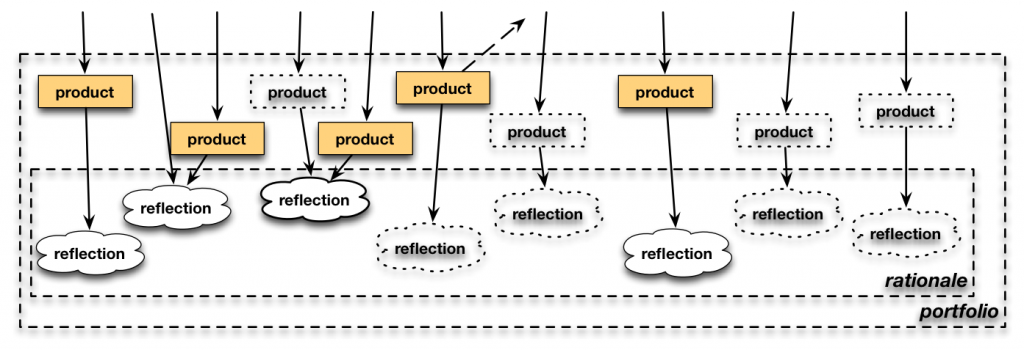

A second component is the output of the activity. It was suggested that activities should generate products, such as solutions to problems, proposals for action, and more. The activity would be structured to generate this product, and the product could either be a reflection itself (e.g. an event review) or tangible output. It could be a document, audio, or even video. If the product itself is not a reflection, there should be one as well, a reflection. Eventually, the product choice and reflection piece will be the responsibility of the learner, and consequently there will be a scaffolding and fading process here too.

A second component is the output of the activity. It was suggested that activities should generate products, such as solutions to problems, proposals for action, and more. The activity would be structured to generate this product, and the product could either be a reflection itself (e.g. an event review) or tangible output. It could be a document, audio, or even video. If the product itself is not a reflection, there should be one as well, a reflection. Eventually, the product choice and reflection piece will be the responsibility of the learner, and consequently there will be a scaffolding and fading process here too.

Note that the product of learner activity could then become content for future activities. The product could similarly be the basis for a subsequent activity.

The reflection itself is a self-evaluation mechanism, that is the learner should be looking at their own work as well as sharing the underlying thinking that led to the resulting product. Peers could and should evaluate other’s products and reflections as an activity as well (getting just a wee bit recursive, but not problematically so). And, of course, the products and reflections are there for mentor evaluation. And, as activities can be social, so too can the products be, and the reflections.

While digital tools aren’t required for this to work, it would certainly make sense from a wide-variety of perspectives to take advantage of digital tools. Rich media would make sense as content, and this could include augmented reality in contexts. Further, creation tools could and should be used to create products and or reflections. Of course, activities too could be digitally based such as simulations, whether desktop or digitally delivered, e.g. simulations or alternate reality games.

The notion is to try to reframe learning as a series of designed activities with guided reflections, and a gradual segue from mentor-designed to learner-owned. Does this resonate?

In a recent

In a recent