Robert Scoble has written about Qualcomm’s announcement of a new level of mobile device awareness. He characterizes the phone transitions from voice (mobile 1.0) to tapping (2.0) to the device knowing what to do (3.0). While I’d characterize it differently, he’s spot on about the importance of this new capability.

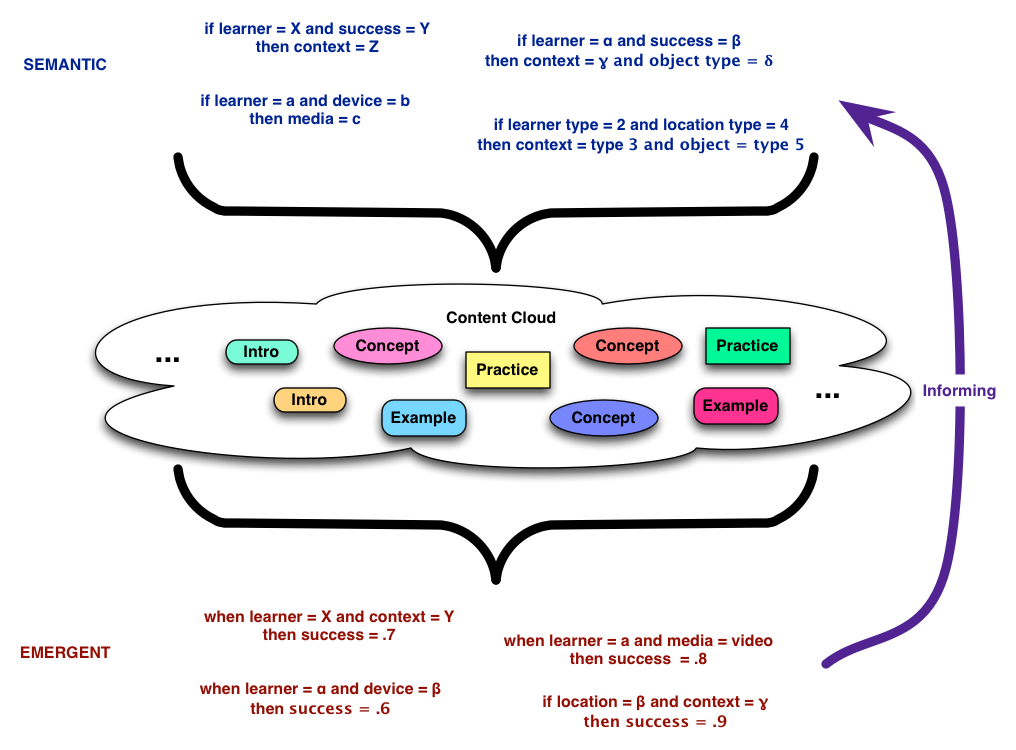

I’ve written before about how the missed opportunity is context awareness, specifically not just location but time. What Qualcomm has created is a system that combines location awareness, time awareness, and the ability to build and leverage a rich user profile. Supposedly, according to Robert, it’s also tapped into the accelerometer, altimeter, whatever sensors there are. It’ll be able to know in pretty fine detail a lot more about where you are and doing.

Gimbal is mostly focused on marketing (of course, sigh), but imagine what we could do for learning and performance support!

We can now know who you are and what you’re doing, so:

- a sales team member visiting a client would get specialized information different than what a field service tech would get at the same location.

- a student of history would get different information at a particular location such as Boston than an architecture student would

- a person learning how to manage meetings more efficiently would get different support than a person working on making better presentations

I’m sure you can see where this is going. It may well be that we can coopt the Gimbal platform for learning as well. We’ve had the capability before, but now it may be much easier by having an SDK available. Writing rules to take advantage of all the sensors is going to be a big chore, ultimately, but if they do the hard yards for their needs, we may be able to ride on the their coattails for ours. It may be an instance when marketing does our work for us!

Mobile really is a game changer, and this is just another facet taking it much further along the digital human augmentation that’s making us much more effective in the moment, and ultimately more capable over time. Maybe even wiser. Think about that.