After my previous article on direct instruction versus guided discovery, some discussion mentioned Engelmann’s Direct Instruction (DI). And, something again pointed me to the most comprehensive survey of educational effects. So, I tracked both of these down, and found some interesting results that both supported, and confounded, my learning. Ultimately, of course, it expanded my understanding, which is always my desire. So it’s time to think a bit deeper about Direct Instruction and Learning Experience Design.

Engelmann’s Direct Instruction is very scripted. It is rigorous in its goals, and has a high amount of responses from learners. Empirically, DI has great success, with some complaints about lack of teacher flexibility. It strikes me as very good for developing core skills like reading and maths. I was worried about the intersection of many responses a minute and more complex tasks, though it appears that’s an issue that has been addressed. I couldn’t find the paper that makes that case, however.

Another direction, however, proved fruitful. John Hattie, an educational researcher, collected and conducted reviews of 800+ meta-analyses to look at what worked (and didn’t) in education. It’s a monumental work, collected in his book Visible Learning. I’d heard of it before, but hadn’t tracked it down. It was time.

And it’s impressive in breadth and depth. This is arguably the single most important work in education. And it opened my eyes in several ways. To illustrate, let me collect for you the top (>.4) impacts found, which have some really interesting implications:

- Reciprocal teaching (.74)

- Providing feedback (.72)

- Teaching student self-verbalization (.67)

- Meta-cognition strategies (.67)

- Direction instruction (.59)

- Mastery learning (.57)

- Goals-challenging (.56)

- Frequent/effects of testing (.46)

- Behavioral organizers (.41)

Reciprocal teaching and meta-cognition strategies coming out highly, a great outcome. And of course I am not surprised to see the importance of feedback. I have to say that I was surprised to see direct instruction and mastery learning coming out so high. So what’s going on? It’s related to what I mentioned in the afore-mentioned article, about just what the definition of DI is.

So, Hattie says: …”what the critics mean by direct instruction is didactic teacher-led talking from the front…” And, indeed, that’s my fear of using the label. He goes on to point out the major steps of DI (in my words):

- Have clear learning objectives: what should the learner be able to do?

- Clear success criteria (which to me is part of 1)

- Engagement: an emotional ‘hook’

- A clear pedagogy: info (models & examples), modeling, checking for understanding

- Guided practice

- Closure of the learning experience

- Reactivation: spaced and varied practice

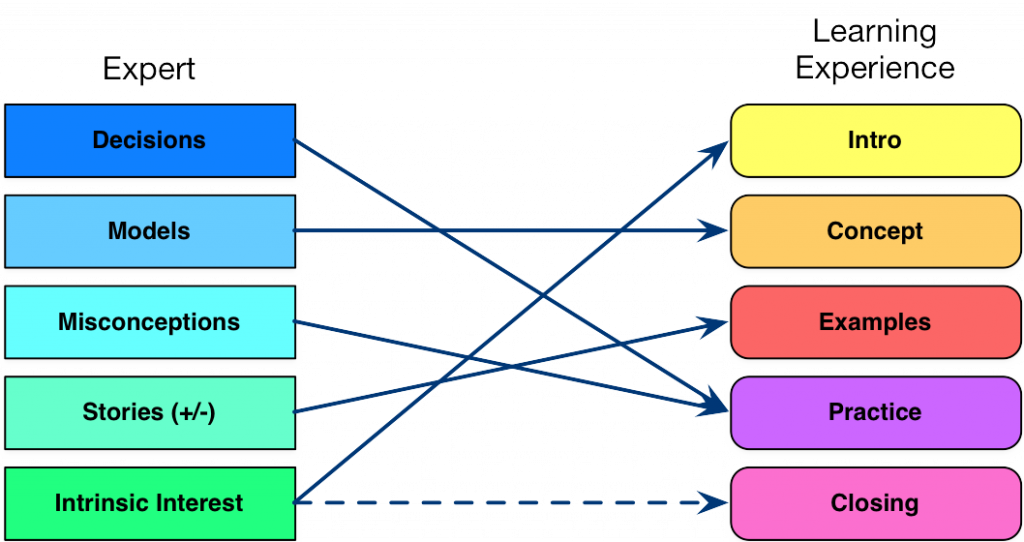

And, of course, this is pretty much everything I argue for as being key to successful learning experience design. And, as I suspected, DI is not what the label would lead you to believe (which I do think is a problem). As I mentioned in a subsequent post, I’ve synthesized my approach across many elements, integrating the emotional elements along with effective education practice (see the alignment). There’s so much more here, but it’s a very interesting result. Direct Instruction and Learning Experience Design have a really nice alignment.

And a perfect opportunity to remind you that I’ll be offering a Learning Experience Design workshop at DevLearn, which will include the results of my continuing investigation (over decades) to create an approach that’s doable and works. Hope to see you there!