You’ll see a lot of vendors/sessions/webinars touting neuroscience or brain-based. And you really shouldn’t believe it. Yes, our brains are composed of neurons, and we do care about what we know about brains. BUT, these aren’t the right terms! Ironically, we have to be smarter than that. Why?

No argument that neuroscience is advancing, rapidly. With powerful tools like MRI, we can understand lots more about what the brain does. And as we do, our understanding overall advances. But for our purposes, neural is the wrong level.

No argument that neuroscience is advancing, rapidly. With powerful tools like MRI, we can understand lots more about what the brain does. And as we do, our understanding overall advances. But for our purposes, neural is the wrong level.

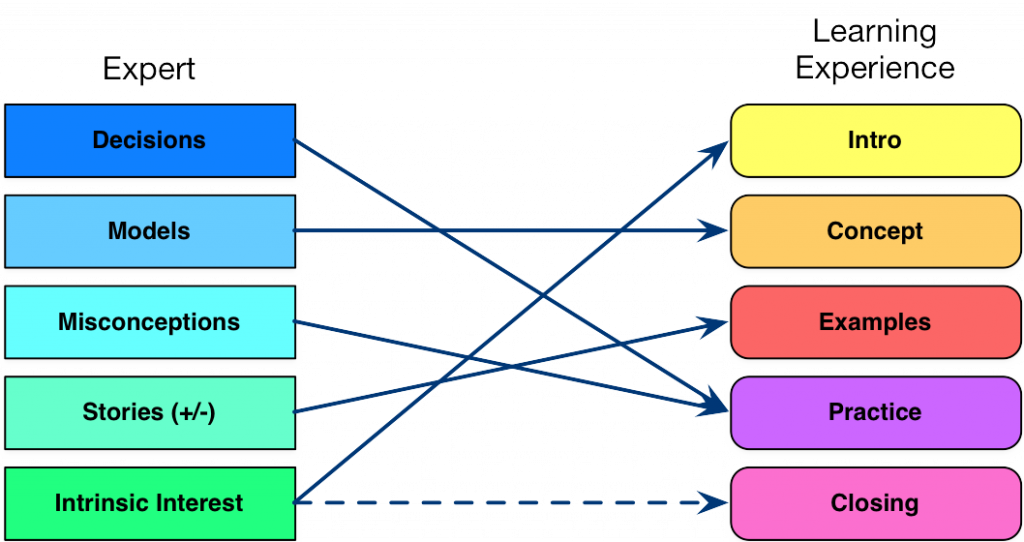

Yes, learning is really about strengthening neural links. However, we don’t address individual neurons. Instead our thinking is really patterns of activation across neurons. So, we activate patterns. And, typically, if we’re addressing higher-level thinking than motor reactions (think: decisions about actions), we’re activating complex combinations of patterns.

To do so, we’re working at the symbolic level. Images representing concepts, diagrams, and language. And this is the cognitive level! It’s the level above neural. And above that, the social. And while it’s about the brain, saying it’s based on the brain is a muddy concept. Do you mean neural, or cognitive, or…? Clarity matters.

Cognitive science as a field was defined to be an integrative approach to everything about our thinking: consciousness, language, emotion, and more. Departments of cognitive science tend to include psychologists, linguists, sociologists, anthropologists, philosophers, and, yes, neuroscientists. For instruction, and other aspects like performance support and informal learning, however, cognitive (or social) is the right level.

And, to be clear, learning sciences are a subset of the cognitive sciences. So you really should have a working understanding of the basics of learning science if you’re designing courses. And of the bigger picture of cognitive science to do the new L&D.

Conceptual clarity about our field, is important to our field. We need to know what we’re doing, and resist hype that is misleading if not flat-out wrong. It’s nice to think we’re doing cool stuff, but not if we don’t have the basics down. Invest in solid learning and performance design first. Then we can get fancy.