In a (rare) fit of tidying, I was moving from one note-taking app to another, and found a diagram I’d jotted, and it rekindled my thinking. The point was characterizing social media in terms of their particular mechanisms of distribution. I can’t fully recall what prompted the attempt at characterization, but one result of revisiting was thinking about the media in terms of whether they’re part of a natural mechanism of ‘show your work’ (ala Bozarth)/’work out loud’ (ala Jarche).

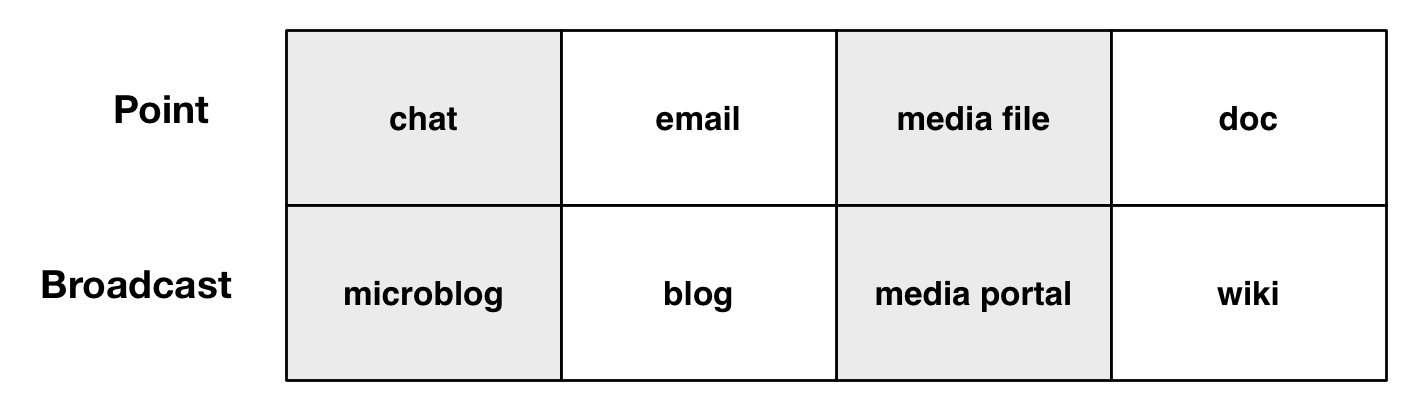

The question revolves around whether the media are point or broadcast, that is whether you specify particular recipients (even in a mailing or group list), or whether it’s ‘out there’ for anyone to access. Now, there are distinctions, so you can have restricted access on the ‘broadcast’ mode, but in principle there’re two different mechanisms at work.

The question revolves around whether the media are point or broadcast, that is whether you specify particular recipients (even in a mailing or group list), or whether it’s ‘out there’ for anyone to access. Now, there are distinctions, so you can have restricted access on the ‘broadcast’ mode, but in principle there’re two different mechanisms at work.

It should be noted that in the ‘broadcast’ model, not everyone may be aware that there’s a new message, if they’re not ‘following’ the poster of the message, but it should be findable by search if not directly. Also, the broadcast may only be an organizational network, or it can be the entire internet. Regardless, there are differences between the two mechanisms.

So, for example, a chat tool typically lets you ping a particular person, or a set list. On the other hand, a microblog lets anyone decide to ‘follow’ your quick posts. Not everyone will necessarily be paying attention to the ‘broadcast’, but they could. Typically, microblogs (and chat) are for short messages, such as requests for help or pointers to something interesting. The limitations mean that more lengthy discussions typically are conveyed via…

Formats supporting unlimited text, including thoughtful reflections, updates on thinking, and more tend to be conveyed via email or blog posts. Again, email is addressed to a specific list of people, directly or via a mail list, openly or perhaps some folks receiving copies ‘blind’ (that is, not all know who all is receiving the message. A blog post (like this), on the other hand, is open for anyone on the ‘system’.

The same holds true for other media files besides text. Video and audio can be hidden in a particular place (e.g. a course) or sent directly to one person. On the other hand, such a message can be hosted on a portal (YouTube, iTunes) where anyone can see. The dialog around a file provides a rich augmentation, just as such can be happening on a blog, or edited RTs of a microblog comment.

Finally, a slightly different twist is shown with documents. Edited documents (e.g. papers, presentations, spreadsheets) can be created and sent, but there’s little opportunity for cooperative development. Creating these in a richer way that allows for others to contribute requires a collaborative document (once known as a wiki). One of my dreams is that we may have collaboratively developed interactives as well, though that still seems some way off.

The point for showing out loud is that point is only a way to get specific feedback, whereas a broadcast mechanism is really about the opportunity to get a more broad awareness and, potentially, feedback. This leads to a broader shared understanding and continual improvement, two goals critical to organizational improvement.

Let me be the first to say that this isn’t necessarily an important, or even new, distinction, it’s just me practicing what I preach. Also, I recognize that the collaborative documents are fundamentally different, and I need to have a more differentiated way to look at these (pointers or ideas, anyone), but here’s my interim thinking. What say you?

#itashare