There’s much talk about 21st Century skills, and rightly so: these skills are the necessary differentiators for individuals and organizations, going forward. If they’re important, how do we incorporate them into systems, and track them? You can’t do them in a vacuum, they only can be brought out in the context of other topics. We can integrate them by hand, and individually assess them, but how do we address them in a technology-enabled world? In the context of a project, here’s where my thinking is going:

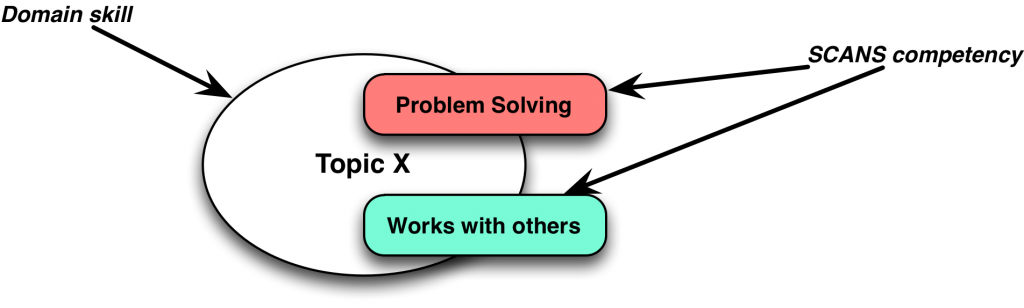

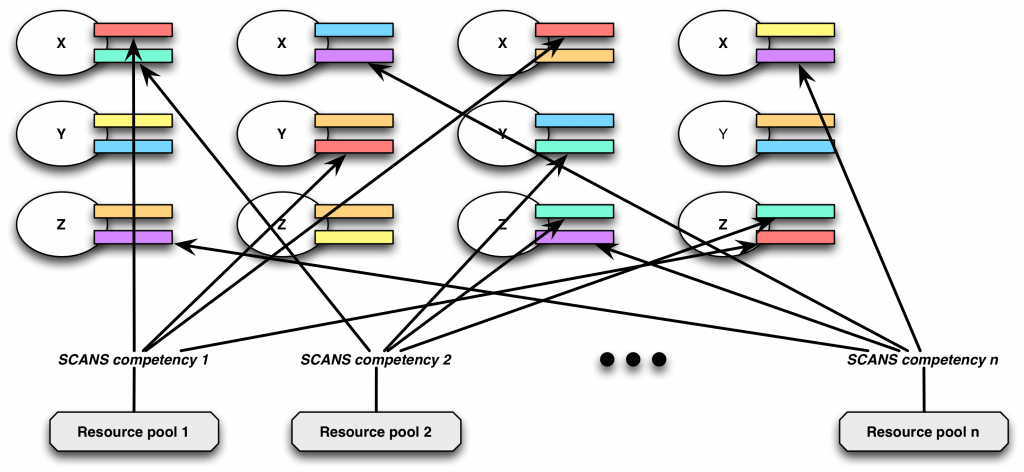

First, you have some domain activity you are having the learner engage in. It might be something in math, science, social studies, whatever (though ideally focused on applied knowledge). Then you give them an assignment, and it might have a number of characteristics: it might be social, e.g. working with others, or problem solving. You could choose many characteristics, e.g. from the SCANS competencies (using information technology, reasoning), that the task entails. That task is labeled with tags associated with the required competency, and tracked via SCORM or more appropriately with the Experience API. There may be more than two, but we’ll stick with that model here.

First, you have some domain activity you are having the learner engage in. It might be something in math, science, social studies, whatever (though ideally focused on applied knowledge). Then you give them an assignment, and it might have a number of characteristics: it might be social, e.g. working with others, or problem solving. You could choose many characteristics, e.g. from the SCANS competencies (using information technology, reasoning), that the task entails. That task is labeled with tags associated with the required competency, and tracked via SCORM or more appropriately with the Experience API. There may be more than two, but we’ll stick with that model here.

So, when we then look across topics that the learner is engaging in, and the characteristics of the assignments, we can look for patterns across competencies. Is there a particular competency that is troubling or excelling? It’s somewhat indirect, but it’s at least one way of systematically embedding meta-learning skills and tracking them. And that’s a lot better than we’re doing now.

So, when we then look across topics that the learner is engaging in, and the characteristics of the assignments, we can look for patterns across competencies. Is there a particular competency that is troubling or excelling? It’s somewhat indirect, but it’s at least one way of systematically embedding meta-learning skills and tracking them. And that’s a lot better than we’re doing now.

Remember the old educational computer games that said ‘develops problem solving skills’? That was misleading. Most of those games ‘required’ problem-solving skills, but no real development of said skills was embedded. A skilled parent or teacher could raise discussion across the problems, but most of the games didn’t. But they could. Moreover, additional 21C resources could be made available for the assignments that required them, and there could be both programmatic or mentor intervention to develop these.

We need to specifically address meta-learning, and with technology we can get evidence. And we should. Now, my two questions are: does the concept make sense? And does the diagram communicate it?