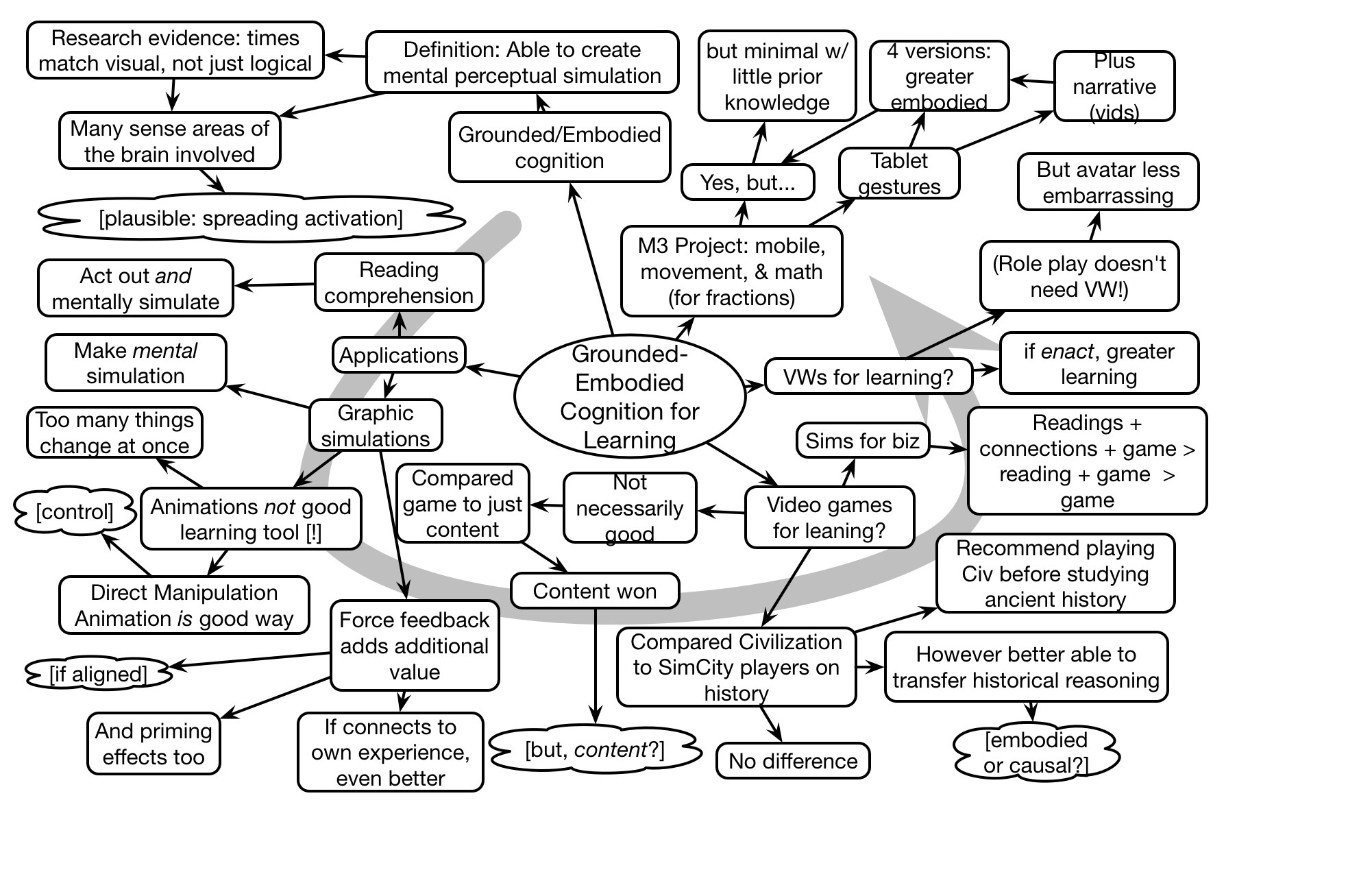

Professor John Black of Columbia Unveristy gave a fascinating talk about how games can leverage “embodied cognition” to achieve deeper learning. The notion is that by physical enaction, you get richer activation, and sponsor deeper learning. It obviously triggered lots of thoughts (mine are the ones in the bubbles :). Lots to ponder.

What’s Your Learning Tool Stack?

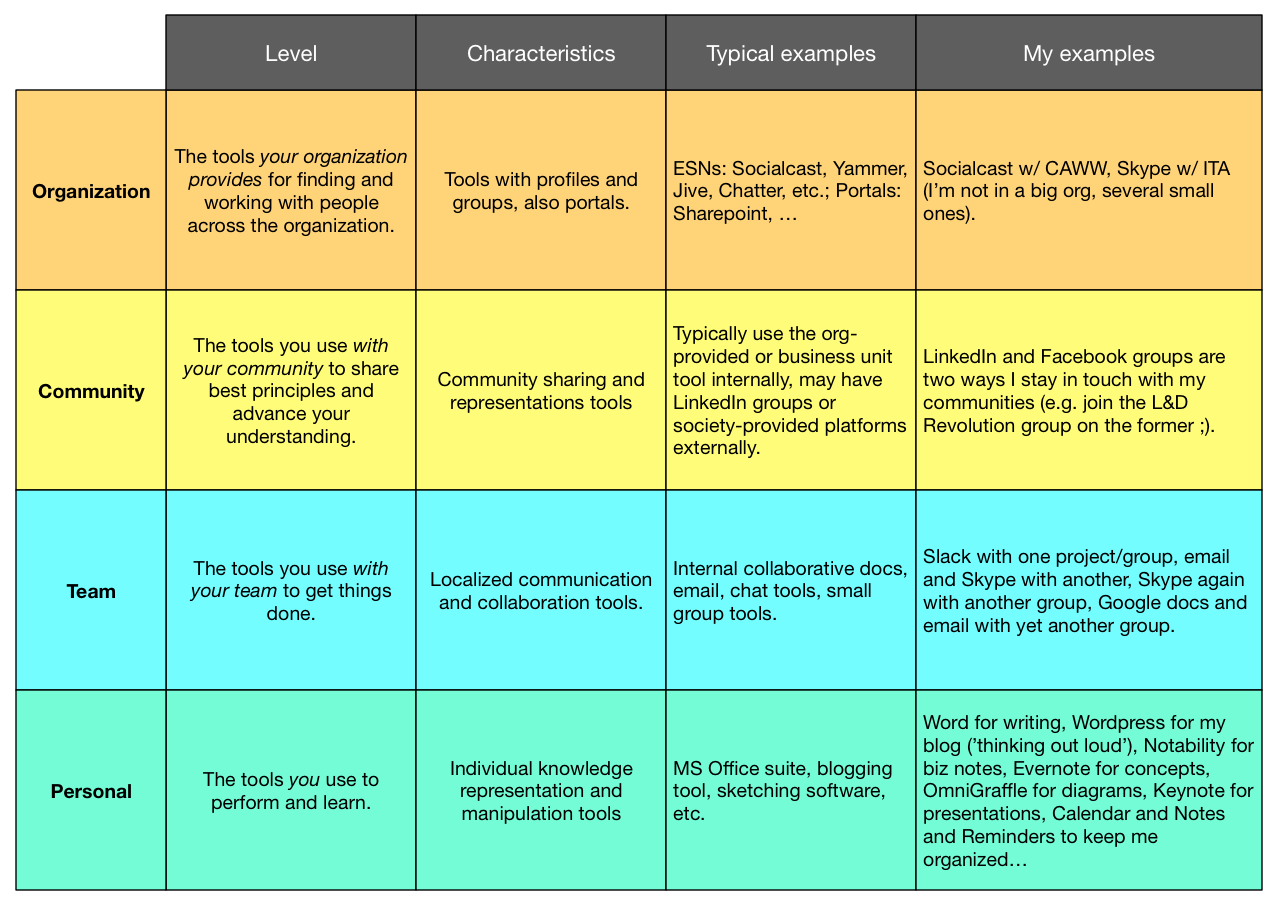

I woke up this morning thinking about the tools we use at various levels. Yeah, my life is exciting ;). Seriously, this is important, as the tools we use and provide through the organization impact the effectiveness with which people can work. And lately, I’ve been hearing the question about “what’s your <x> stack” [x|x=’design’, ‘development’, …]. What this represents is people talking about the tools they use to do their jobs, and I reckon it’s important for us to talk about tools for learning. You can see the results of Jane Hart’s annual survey, but I’m carving it up into a finer granularity, because I think it changes depending on the ‘level’ at which you’re working, ala the Coherent Organization. So, of course, I created a diagram.

What we’re talking about here, starting at the bottom, are the tools you personally use for learning. Or, of course, the ones others use in your org. So this is how you represent your own understandings, and manipulate information, for your own purposes. For many people in organizations, this is likely to include the MS Office Suite, e.g. Word, PowerPoint, and Excel. Maybe OneNote? For me, it’s Word for writing, OmniGraffle for diagramming (as this one was created in), WordPress for this blog (my thinking out loud; it is for me, at least in the first instance), and a suite of note taking software (depending on type of notes) and personal productivity.

What we’re talking about here, starting at the bottom, are the tools you personally use for learning. Or, of course, the ones others use in your org. So this is how you represent your own understandings, and manipulate information, for your own purposes. For many people in organizations, this is likely to include the MS Office Suite, e.g. Word, PowerPoint, and Excel. Maybe OneNote? For me, it’s Word for writing, OmniGraffle for diagramming (as this one was created in), WordPress for this blog (my thinking out loud; it is for me, at least in the first instance), and a suite of note taking software (depending on type of notes) and personal productivity.

From there, we talk about team tools. These are to manage communication and information sharing between teams. This can be email, but increasingly we’re seeing dedicated shared tools being supported, like Slack, that support creating groups, and archive discussions and files. Collaborative documents are a really valuable tool here so you’re not sending around email (though I’m doing that with one team right now, but it’s only back forth, not coordinating between multiple people, at least on my end!). Instead, I coordinate with one group with Slack, a couple others with Skype and email, and am using Google Docs and email with another.

From there we move up to the community level. Here the need is to develop, refine, and share best principles. So the need is for tools that support shared representations. Communities are large, so we need to start having subgroups, and profiles become important. The organization’s ESN may support this, though (and probably unfortunately) many business units have their own tools. And we should be connecting with colleagues in other organizations, so we might be using society-provided platforms or leverage LinkedIn groups. There’s also probably a need to save community-specific resources like documents and job aids, so there may be a portal function as well. Certainly ongoing discussions are supported. Personally, without my own org, I tap into external communities using tools like LinkedIn groups (there’s one for the L&D Revolution, BTW!), and Facebook (mostly friends, but some from our own field).

Finally, we get to the org level. Here we (should) see organization wide Enterprise Social Networks like Jive and Yammer, etc. Also enterprise wide portal tools like Sharepoint. Personally, I work with colleagues using Socialcast in one instance, and Skype with another (tho’ Skype really isn’t a full solution).

So, this is a preliminary cut to show my thinking at inception. What have I forgotten? What’s your learning stack?

Heading in the right direction

Most of our educational approaches – K12, Higher Ed, and organizational – are fundamentally wrong. What I see in schools, classrooms, and corporations are information presentation and knowledge testing. Which isn’t bad in and of itself, except that it won’t lead to new abilities to do! And this bothers me.

As a consequence, I took a stand trying to create a curricula that wasn’t about content, but instead about action. I elaborated it in some subsequent posts, trying to make clear that the activities could be connected and social, so that you could be developing something over time, and also that the output of the activity produced products – both the work and thoughts on the work – that serve as a portfolio.

I just was reading and saw some lovely synergistic thoughts that inspire me that there’s hope. For one, Paul Tough apparently wrote a book on the non-cognitive aspects of successful learners, How Children Succeed, and then followed it up with Helping Children Succeed, which digs into the ignored ‘how’. His point is that elements like ‘grit’ that have been (rightly) touted aren’t developed in the same way cognitive skills are, and yet they can be developed. I haven’t read his book (yet), but in exploring an interview with him, I found out about Expeditionary Learning.

And what Expeditionary Learning has, I’m happy to discover, is an approach based upon deeply immersive projects that integrate curricula and require the learning traits recognized as important. Tough’s point is that the environment matters, and here are schools that are restructured to be learning environments with learning cultures. They’re social, facilitated, with meaningful goals, and real challenges. This is about learning, not testing. “A teacher’s primary task is to help students overcome their fears and discover they can do more than they think they can.”

And I similarly came across an article by Benjamin Riley, who’s been pilloried as the poster-child against personalization. And he embraces that from a particular stance, that learning should be personalized by teachers, not technology. He goes further, talking about having teachers understand learning science, becoming learning engineers. He also emphasizes social aspects.

Both of these approaches indicate a shift from content regurgitation to meaningful social action, in ways that reflect what’s known about how we think, work, and learn. It’s way past time, but it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t keep striving to do better. I’ll argue that in higher ed and in organizations, we should also become more aware of learning science, and on meaningful activity. I encourage you to read the short interview and article, and think about where you see leverage to improve learning. I’m happy to help!

Learning in Context

In a recent guest post, I wrote about the importance of context in learning. And for a featured session at the upcoming FocusOn Learning event, I’ll be talking about performance support in context. But there was a recent question about how you’d do it in a particular environment, and that got me thinking about the the necessary requirements.

As context (ahem), there are already context-sensitive systems. I helped lead the design of one where a complex device was instrumented and consequently there were many indicators about the current status of the device. This trend is increasing. And there are tools to build context-sensitive helps systems around enterprise software, whether purchased or home-grown. And there are also context-sensitive systems that track your location on mobile and allow you to use that to trigger a variety of actions.

Now, to be clear, these are already in use for performance support, but how do we take advantage of them for learning. Moreover, can we go beyond ‘location’ specific learning? I think we can, if we rethink.

So first, we obviously can use those same systems to deliver specific learning. We can have a rich model of learning around a system, so a detailed competency map, and then with a rich profile of the learner we can know what they know and don’t, and then when they’re at a point where there’s a gap between their knowledge and the desired, we can trigger some additional information. It’s in context, at a ‘teachable moment’, so it doesn’t necessarily have to be assessed.

This would be on top of performance support, typically, as they’re still learning so we don’t want to risk a mistake. Or we could have a little chance to try it out and get it wrong that doesn’t actually get executed, and then give them feedback and the right answer to perform. We’d have to be clear, however, about why learning is needed in addition to the right answer: is this something that really needs to be learned?

I want to go a wee bit further, though; can we build it around what the learner is doing? How could we know? Besides increasingly complex sensor logic, we can use when they are. What’s on their calendar? If it’s tagged appropriately, we can know at least what they’re supposed to be doing. And we can develop not only specific system skills, but more general business skills: negotiation, running meetings, problem-solving/trouble-shooting, design, and more.

The point is that our learners are in contexts all the time. Rather than take them away to learn, can we develop learning that wraps around what they’re doing? Increasingly we can, and in richer and richer ways. We can tap into the situational motivation to accomplish the task in the moment, and the existing parameters, to make ordinary tasks into learning opportunities. And that more ubiquitous, continuous development is more naturally matched to how we learn.

Learning in context

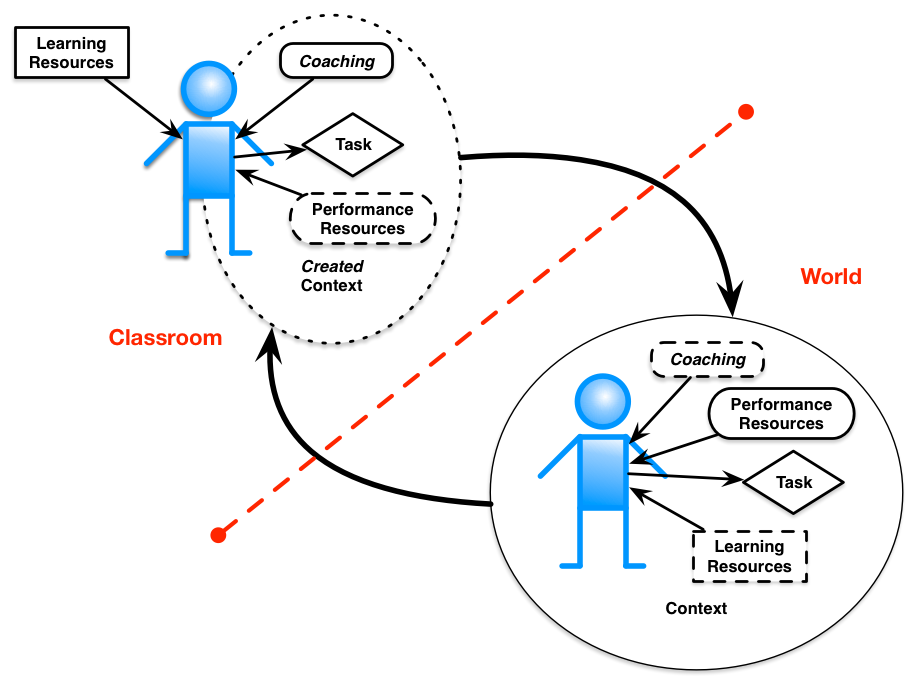

In preparation for the upcoming FocusOn Learning Conference, where I’ll be running a workshop about cognitive science for L&D, not just for learning but also for mobile and performance support, I was thinking about how context can be leveraged to provide more optimal learning and performance. Naturally, I had to diagram it, so let me talk through it, and you let me know what you think.

What we tend to do, as a default, is to take people away from work, provide the learning resources away from the context, then create a context to practice in. There are coaching resources, but not necessarily the performance resources. (And I’m not even mentioning the typical lack of sufficient practice.) And this makes sense when the consequences of making a mistake on the task are irreversible and costly. E.g. medicine, transportation. But that’s not as often as we think. And there’s an alternative.

What we tend to do, as a default, is to take people away from work, provide the learning resources away from the context, then create a context to practice in. There are coaching resources, but not necessarily the performance resources. (And I’m not even mentioning the typical lack of sufficient practice.) And this makes sense when the consequences of making a mistake on the task are irreversible and costly. E.g. medicine, transportation. But that’s not as often as we think. And there’s an alternative.

We can wrap the learning around the context. Our individual is in the world, and performing the task. There can be coaching (particularly at the start, and then gradually removed as the individual moves to acceptable competence). There are also performance resources – job aids, checklists, etc – in the environment. There also can be learning resources, so the individual can continue to self-develop, particularly in the increasingly likely situation that the task has some ambiguity or novelty in it. Of course, that only works if we have a learner capable of self learning (hint hint).

The problems with always taking people away from their jobs are multiple:

- it is costly to interrupt their performance

- it can be costly to create the artificial context

- the learning has a lower likelihood to make it back to the workplace

Our brains don’t learn in an event model, they learn in little bits over time. It’s more natural, more effective, to dribble the learning out at the moment of need, the learnable moment. We have the capability, now, to be more aware of the learner, to deliver support in the moment, and develop learners over time. The way their brains actually learn. And we should be doing this. It’s more effective as well as more efficient. It requires moving out of our comfort zone; we know the classroom, we know training. However, we now also know that the effectiveness of classroom training can be very limited.

We have the ability to start making learning effective as well as efficient. Shouldn’t we do so?

Deeper Learning Reading List

So, for my last post, I had the Revolution Reading List, and it occurred to me that I’ve been reading a bit about deeper learning design, too, so I thought I’d offer some pointers here too.

The starting point would be Julie Dirksen’s Design For How People Learn (already in it’s 2nd edition). It’s a very good interpretation of learning research applied to design, and very readable.

A new book that’s very good is Make It Stick, by Peter Brown, Henry Roediger III, and Mark McDaniel, the former being a writer who’s worked with two scientists to take learning research into 10 principles.

And let me mention two Ruth Clark books. One with Dick Mayer from UCSB, e-Learning and the Science of Instruction, that focuses on the use of media. A second with Frank Nguyen and the wise John Sweller, Efficiency in Learning, focuses on cognitive load (which has many implications, including some overlap with the first).

Patti Schank has come out with a concise compilation of research called The Science of Learning that’s available to ATD members. Short and focused with her usual rigor. If you’re not an ATD member, you can read her blog posts that contributed (click ‘View All’).

Dorian Peters book on Interface Design for Learning also has some good learning principles as well as interface design guidance. It’s not the same for learning as for doing.

Of course, a classic is a compilation of research by a blue-ribbon team lead by John Bransford, How People Learn, (online or downloadable). Voluminous, but pretty much state of the art.

Another classic is the Cognitive Apprenticeship model of Allen Collins & John Seely Brown. A holistic model abstracted across some seminal work, and quite readable.

The Science of Learning Center has an academic integration of research to instruction theory by Ken Koedinger, et al, The Knowledge-Learning-Instruction Framework, that’s freely available as a PDF.

I’d be remiss if I don’t point out the Serious eLearning Manifesto, which has 22 research principles underneath the 8 values that differentiate serious elearning from typical versions. If you buy in, please sign on!

And, of course, I can point you to my own series for Learnnovators on Deeper ID.

So there you go with some good material to get you going. We need to do better at elearning, treating it with the importance it deserves. These don’t necessarily tell you how to redevelop your learning design processes, but you know who can help you with that. What’s on your list?

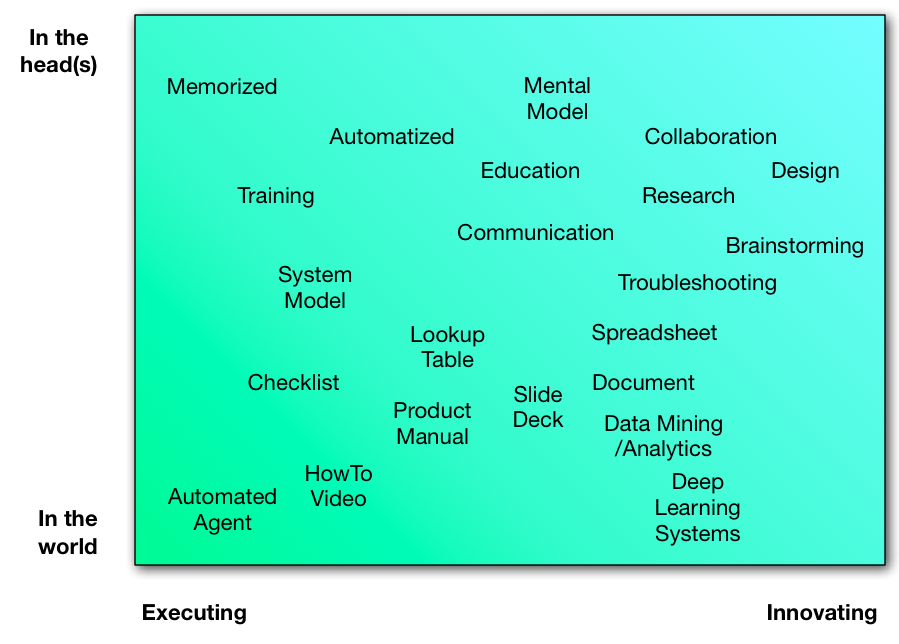

Work Experiment

At a point some days ago, I got the idea to map out different activities by their role as executing versus innovating, and whether it’s in the head or in the world. And I’ve been playing with it since. I’m mapping some ways of getting work done, at least the mental aspects, across those dimensions.

I’m not sure I’ve got things in the right places. I’m not even sure what it really means. I’ve some ideas, but I think I’m going to try something new, and ask you what you think it means. So, what’s interesting and/or important here?

Top 10 Tools for Learning 2016

It’s that time again: Jane Hart is running her 2016 (and 10th!) Top 100 Tools for Learning poll. It’s a valuable service, and points out some interesting things and it’s interesting to see the changes over time. It’s also a way to see what others are using and maybe find some new ideas. She’s now asking that you categorize them as Education, Training & Performance Support, and/or Personal Learning & Productivity. All of mine fall in the latter category, because my performance support tools are productivity tools! So here’re my votes, FWIW:

Google Search is, of course, still my top tool. I’m looking up things several if not many times a day. It’s often a gateway to Wikipedia, which I heavily rely on, but a number of times I find other sources that are equally valuable, such as research or practice sites that have some quality inputs.

Books are still a major way I learn. Yes, I check out books from the library and read them. I also acquire and read them on my iPad, such as Jane’s great Modern Workplace Learning. In my queue is Jane Bozarth’s Show Your Work.

Twitter is a go-to. I am pointed to many serendipitously interesting things, and of course I point to things as well. The learning chats I participate in are another way twitter helps. Tweetdeck is my twitter tool; columns are a must.

Skype is a tool I use for communicating with folks to get things done, but also to have conversations (e.g. with my ITA colleagues), whether chat or voice.

Facebook is also a way I stay in touch with friends and colleagues (those colleagues that I also consider friends; Facebook is more a personal learning tool than a business tool for me).

LinkedIn is a way to stay in touch with people, and in particular the L&D Revolution group is where I want to keep the dialog alive about the opportunity. The articles in LinkedIn are occasionally of interest too, and it’s always an education to see who wants to link ;).

WordPress is my blogging tool (where you’re at right now), and it’s a way I think ‘out loud’ and the feedback I get is a wonderful way to learn. Things that eventually appear in presentations and writing typically appear here first, and some of the work I do for others manifests here (typically anonymized).

Word is my go-to writing tool, and while I use Pages at times too (e.g. if I’m traveling with my iPad), Word is my industrial strength tool. Writing forces me to get concrete about my thinking.

Omnigraffle is as always my diagramming tool, and it’s definitely a way I express and refine my thinking. Obviously, you’ll see my diagrams here, but also in presentations and articles/chapters/books. And, of course, my mindmaps.

Keynote is my presentation creating tool. I sometimes have to export to PowerPoint, but Keynote is where I work natively. It helps me turn my ideas from diagrams and/or writing into a story to tell with visual support.

So those are my ‘learning’ tools, for now. Some are ‘content’, some are social media, some are personal representational tools, but reading and talking with others and representing my own thinking are major learning activities for me.

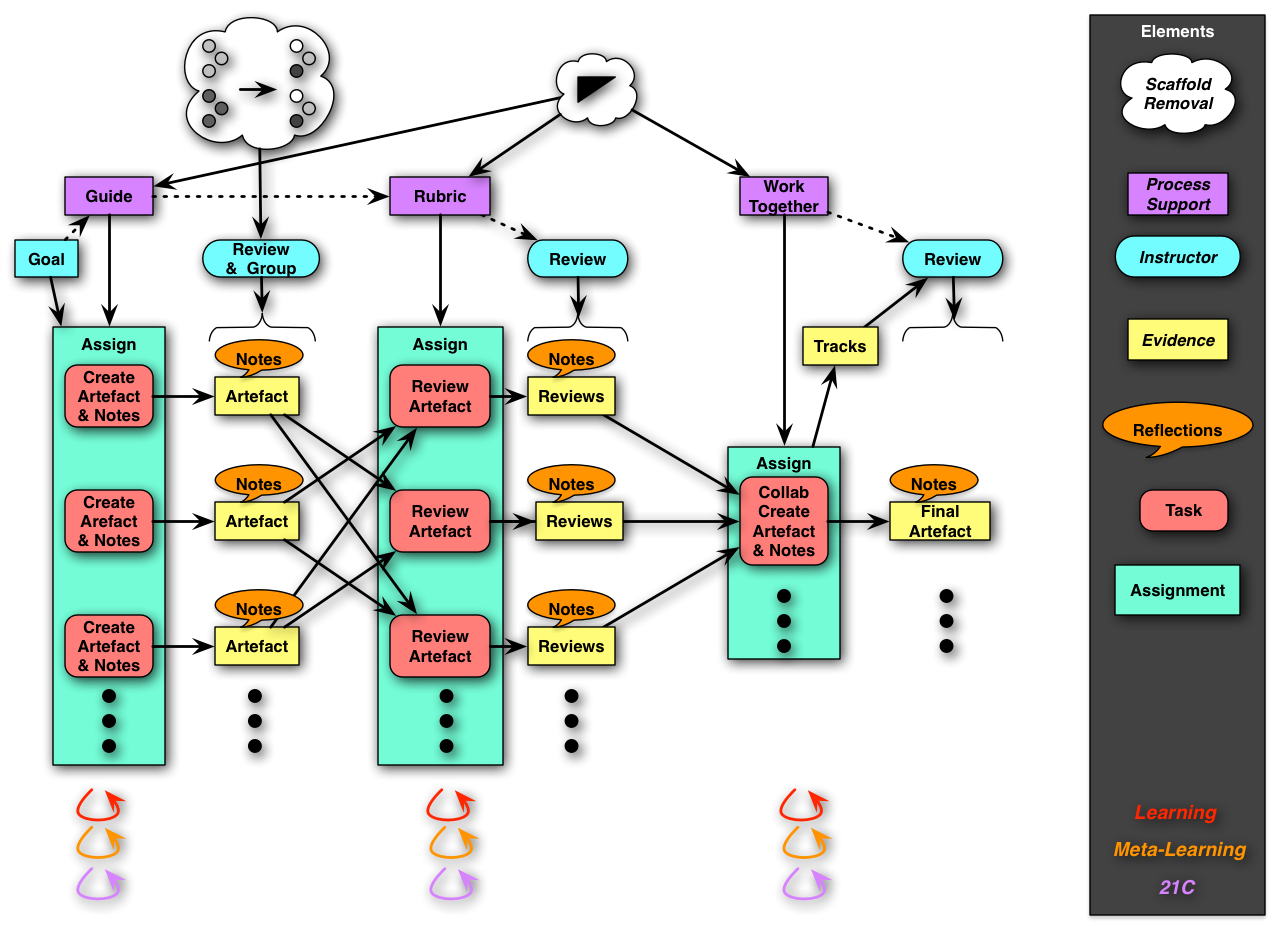

A complex look at task assignments

I was thinking (one morning at 4AM, when I was wishing I was asleep) about designing assignment structures that matched my activity-based learning model. And a model emerged that I managed to recall when I finally did get up. I’ve been workshopping it a bit since, tuning some details. No claim that it’s there yet, by the way.

And I’ll be the first to acknowledge that it’s complex, as the diagram represents, but let me tease it apart for you and see if it makes sense. I’m trying to integrate meaningful tasks, meta-learning, and collaboration. And there are remaining issues, but let’s get to the model first.

And I’ll be the first to acknowledge that it’s complex, as the diagram represents, but let me tease it apart for you and see if it makes sense. I’m trying to integrate meaningful tasks, meta-learning, and collaboration. And there are remaining issues, but let’s get to the model first.

So, it starts by assigning the learners a task to create an artefact. (Spelling intended to convey that it’s not a typical artifact, but instead a created object for learning purposes.) It could be a presentation, a video, a document, or what have you. The learner is also supposed to annotate their rationale for the resulting design as well. And, at least initially, there’s a guide to principles for creating an artefact of this type. There could even be a model presentation.

The instructor then reviews these outputs, and assigns the student several others to review. Here it’s represented as 2 others, but it could be 4. The point is that the group size is the constraining factor.

And, again at least initially, there’s a rubric for evaluating the artefacts to support the learner. There could even be a video of a model evaluation. The learner writes reviews of the two artefacts, and annotates the underlying thinking that accompanies and emerges. And the instructor reviews the reviews, and provides feedback.

Then, the learner joins with other learners to create a joint output, intended to be better than each individual submission. Initially, at least, the learners will likely be grouped with others that are similar. This step might seem counter intuitive, but while ultimately the assignments will be to widely different artefacts, initially the assignment is lighter to allow time to come to grips with the actual process of collaborating (again with a guide, at least initially). Finally, the final artefacts are evaluated, perhaps even shared with all.

Several points to make about this. As indicated, the support is gradually faded. While another task might use another artefact, so the guides and rubrics will change, the working together guide can gradually first get to higher and higher levels (e.g. starting with “everyone contributes to the plan”, and ultimately getting to “look to ensure that all are being heard”) and gradually being removed. And the assignment to different groups goes from alike to as widely disparate as possible. And the tasks should eventually get back to the same type of artefact, developing those 21 C skills about different representations and ways of working. The model is designed more for a long-term learning experience than a one-off event model (which we should be avoiding anyways).

The artefacts and the notes are evidence for the instructor to look at the learner’s understanding and find a basis to understand not only their domain knowledge (and gaps), but also their understanding of the 21st Century Skills (e.g. the artefact-creation process, and working and researching and…), and their learning-to-learn skills. Moreover, if collaborative tools are used for the co-generation of the final artefact, there are traces of the contribution of each learner to serve as further evidence.

Of course, this could continue. If it’s a complex artefact (such as a product design, not just a presentation), there could be several revisions. This is just a core structure. And note that this is not for every assignment. This is a major project around or in conjunction with other, smaller, things like formative assessment of component skills and presentation of models may occur.

What emerges is that the learners are learning about the meta-cognitive aspects of artefact design, through the guides. They are also meta-learning in their reflections (which may also be scaffolded). And, of course, the overall approach is designed to get the valuable cognitive processing necessary to learning.

There are some unresolved issues here. For one, it could appear to be heavy load on the instructor. It’s essentially impossible to auto-mark the artefacts, though the peer review could remove some of the load, requiring only oversight. For another, it’s hard to fit into a particular time-frame. So, for instance, this could take more than a week if you give a few days for each section. Finally, there’s the issue of assessing individual understanding.

I think this represents an integration of a wide spread of desirable features in a learning experience. It’s a model to shoot for, though it’s likely that not all elements will initially be integrated. And, as yet, there’s no LMS that’s going to track the artefact creation across courses and support all aspects of this. It’s a first draft, and I welcome feedback!

Cheers for #chats

For a reason I can no longer recall, I was thinking about twitter chats. Two, in particular, came to mind – #lrnchat and #chat2lrn – for one specific reason. And I think it’s worth calling attention to them for that reason.

They have a format that for an hour, questions come out every few minutes or so to the hashtag associated with the chat. And the participants answer the questions, continuing to use the hashtag. One of the interesting phenomena to me is that unlike many conversations, the answers can diverge as much as converge, and that’s OK. The topics vary, and in the questions and answers, you can learn a lot. It’s valuable to even see what the questions are, as well as the responses by others.

What’s fun about them is that people have fun with it; they riff off others’ posts in fun ways, they make silly tweets, and are generally real people as well as answering the questions. They truly are learning events, and yet very human as well. When you finally meet in person a participant you’ve met online, it can be much more familiar than meeting someone you’ve heard about, because you’ve interacted with them. And while the community that participates isn’t huge, the learnings and insights are, and percolate through subsequent work, eventually impacting the industry.

Not completely coincidentally, both are on Thursdays: #lrnchat runs pretty much every Thursday US evening (8:30 ET, 5:30 PT) for an hour, and #chat2lrn runs every other week at 11 AM EST (which is 8 AM PDT when the US is in Daylight Savings Time). What’s amazing is that they run!

What you need to know about these two chats (and others as well, I suspect), my specific issue here, is that they’re fully volunteer run. That means that a group of folks has to decide a topic in advance, craft a series of questions, many times arrange an associated post, and arrange to get the questions posted at the appropriate time. This is a significant amount of work to achieve week in and week out. And I know, because I was a #lrnchat moderator for a number of years!

So we owe these folks a big thanks for continuing on for a rewarding but effortful task. All these people have other jobs, but their contributions help all of us. There are other chats (specifically #guildchat, Fridays at 2 PM PT, 11AM ET) that follow the same format, but there the principals are salaried. Still, the fact that the organization provides resources to support them is appreciated, though they get some marketing capital as a return.

So I want to point out that the folks at lrnchat and chat2lrn are owed thanks by the community (and all the other chats that others participate in that are supported by volunteers and organizations). I salute you!