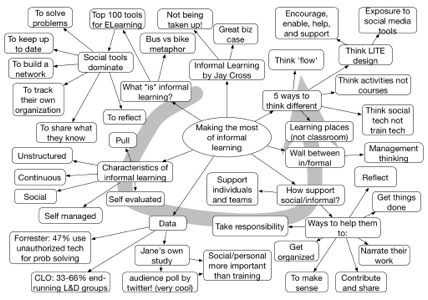

Jane Hart, in her personable style, told a compelling story of the what, why, and how of informal learning. She suggested it was about self-directed learning, that it’s already happening, but that there are valuable ways the L&D group can assist and support.

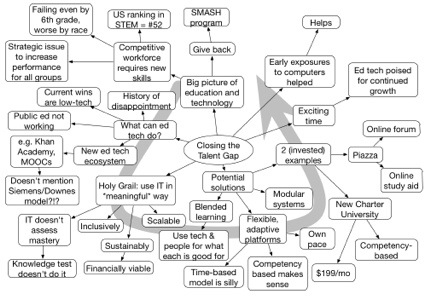

Mitch Kapor #iel12 Keynote Mindmap

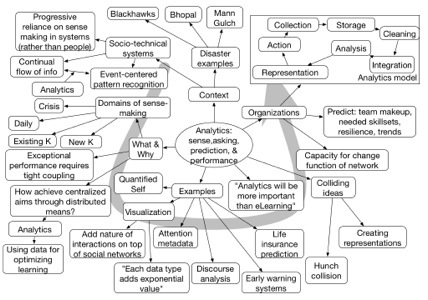

George Siemens #iel12 Keynote Mindmap

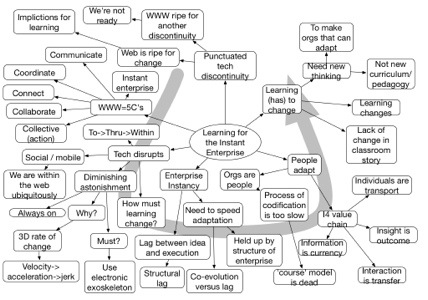

Tony O’Driscoll #iel12 Keynote Mindmap

Tony O’Driscoll kicked off the Innovations in eLearning Symposium with an entertaining and apt tour of the changes in business owing to information change, and the need to adapt. My take was that organizations have to become in a more organic relationship with their ecosystem by empowering their people to engage and act. His final message was that the learning community are the folks who have to figure this out and engage.

Taking the step

A while ago, I wrote an article in eLearnMag, stating that better design doesn’t take longer. In it, I suggested that while there would be an initial hiccup, eventually better design doesn’t take longer: the analysis process is different, but no less involved, the design process is deeper but results in less overall writing, and of course the development is largely the same. And I’m interested in exposing what I mean by the hiccup.

What surprised me is that I haven’t seen more movement. Of course, if you’re a one-person shop, the best you could probably do is attend a ‘Deeper ID’ workshop. But if you’re producing content on a reasonable scale, you should realize that there are several reasons you should be taking this on.

Most importantly, it’s for effectiveness. The learning I see coming out of not only training shops and custom content houses, but also internal units, is just not going to make a difference. If you’re providing knowledge and a knowledge test, I don’t care how well produced it is, it’s not going to make a difference. This is core to a unit’s mission, it seems to me.

It’s also a case of “not if, but when” when someone is going to come in with an effective competing approach. If you can’t do better, you’re going to be irrelevant. If you’re producing for others, your market will be eaten. If you’re producing internally, your job will be outsourced.

It’s also a case of “not if, but when” when someone is going to come in with an effective competing approach. If you can’t do better, you’re going to be irrelevant. If you’re producing for others, your market will be eaten. If you’re producing internally, your job will be outsourced.

Overall, it’s about not just surviving, but thriving.

Yes, the nuances are subtle, and it’s still possible to sell well-produced but not well-designed material, but that can’t last. People are beginning to wake up to the business importance of effective investments in learning, and the emergence of alternate models (Khan Academy, MOOCs, the list goes on) is showing new ways that will have people debating approaches. It may take a while, but why not get the jump on it?

And it’s not about just running a workshop. I do those, and like to do them, but I never pretend that they’re going to make as big a difference as could be achieved. They can’t, because of the forgetting curve. What would make a big difference isn’t much more, however. It’s about reactivating that knowledge and reapplying.

What I envision (and excuse me if I make this personal, but hey, it’s what I do and have done successfully) is getting to know the design processes beforehand, and customizing the workshop to your workflow: your business, your processes of working with SMEs, your design process, your tools, and representative samples of existing work. Then we run a workshop where we use your examples. Working through the process, exploring the deeper concepts, putting them into practice, and reflecting to cement the learning. Probably a day. People have found this valuable in an of itself.

However, I want to take it just a step further. I’ve found that being sent samples of subsequent work and commenting on it in several joint sessions is what makes the real difference. This reactivates the knowledge, identifies the ongoing mistakes, and gives a chance to remediate them. This is what makes it stick, and leads to meaningful change. You have to manage this in a non-threatening way, but that’s doable.

There are more intrusive, higher-overhead ways, but I’m trying to strike a balance between high value and minimal intensiveness to make a pragmatic but successful change. I’d bet that 90% of the learning being developed could be improved by this approach (which means that 90% of the learning being developed really isn’t a worthwhile investment!). It seems so obvious, but I’m not seeing the interest in change. So, what am I missing?

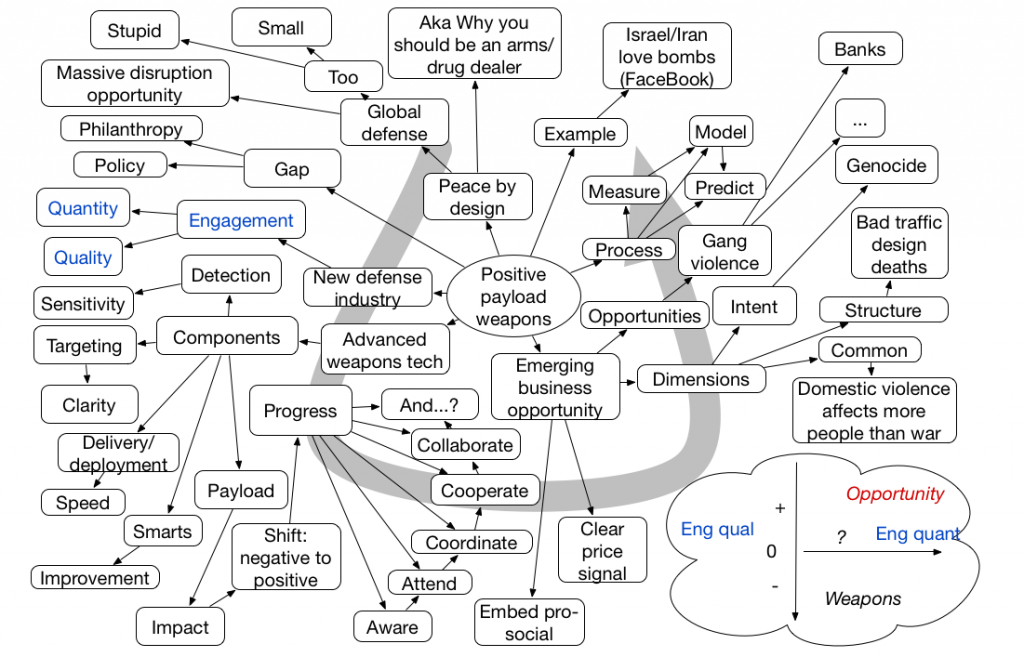

Positive Payload Weapons Presentation Mindmap

The other evening I went off to hear an intriguing sounding presentation on Positive Payload Weapons by Margarita Quihuis (who really just introduced the session) and Mark Nelson. As I sometimes do, I mind mapped it.

I have to say it’s an intriguing framework, but it appeared that they’ve not yet really put it into practice. In short, as the diagram in the lower right suggests, weapons have evolved to do more damage at greater range (from knives one on one to atomic bombs across the world). What could we do to evolve doing more good at greater range? From personal kudos to, well, that’s the open question. They cited the Israel-Iran Love Bombs as an example, and the tactical response.

Oh, yeah, the drug part is the serotonin you get from doing positive things (or something like that).

Applying Expertise

I’m trying to get my mind around how the information we’re finding out about expertise matches to the types of problems people face. Clearly, you want to align your investments appropriately to situations you face. If you look across the literature on expertise, and the recent writing on how our brains work (c.f. Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow), you see an emerging picture of expertise. When you combine this with the situations organizations are increasingly facing, you recognize that we need to get more granular about the types of problems we’re facing and the solutions we have on tap.

Starting with the types of problems, there are more than just the problems we know and the ones we don’t. When you look at the Cynefin model, which characterizes the types of problems we face, we see what types of expertise are helpful. Beyond work that should be automated, there are formulaic types of complicated problems that can be outsourced or accomplished by skilled or well-supported practitioners. Then there are the complex problems that require deeper expertise. Beyond that is the chaotic state where you have to try something to move it into one of the other states, and there are certainly reasons to believe that deep expertise .

So now we look at what’s known about our knowledge. We’ve known for a while that expertise is slowly accumulated, and becomes deeper in ways that are hard to unpack (hence why you need some detailed approaches to get at their understanding). What’s also becoming clear is that this ability to make expert judgements, once compiled away, is most effective in quick (not laborious) application, with a caveat. As Kahneman tells us, this expertise needs to be developed in a field that is “sufficiently regular to be predictableâ€, and in which the expert gets quick and decisive feedback on whether he did the right or the wrong thing. Otherwise, you need to do the hard yards, the slow thinking that’s effortful and systematic. Now, if it’s out of your area of expertise but a known problem, you have two choices: either take a well-known (and appropriate) but laborious approach, or hire the appropriate expertise. If it’s a relatively novel situation, either unique or new, you’ll need a different type of expertise.

We can infer that having a rich suite of models and frameworks helps in circumstances where the right solution isn’t obvious. The conclusion is clear: advanced experts may not immediately know the solution if the problem is reasonably complex (if so, you can get by with a practitioner), but their deeply developed intuition, based upon experience, and associated approaches to those types of problems will have a higher likelihood of finding a solution. Particularly if their expertise spans problem-solving in general, and specific expertise in at least some of the involved domains. Experience solving complex problems, and having a deep and broad conceptual background increases the likelihood of a systemic and comprehensive solution.

To think about it another way, this article makes a distinction between puzzles and mysteries. Puzzles have an answer, once you identify the information needed, collect it, and execute against it. This is the ‘Complicated’ part of the Cynefin situation. Mysteries are where you can’t know what will happen, and you have to experiment. This is the ‘Complex’ or ‘Chaotic’ parts of the model. You’re better off in the latter two if you’ve got good systems thinking, and a suite of useful models in your quiver.

So, when facing a problem, you have to characterize it: is this a puzzle where someone has an off-the-shelf solution “ah, we know that pain, and we solve it this way”, versus the mystery situation where it’s not clear how things will sort out, and you need a much richer conceptual background to address it. In the former case, you can find vendors or consultants with specific expertise. In the latter, the implication clearly is that you want someone who’s been thinking and doing this stuff as long as possible. You want someone who can guide some experiments.

The risk of trying to solve the complex problems with off-the-shelf solutions or DIY is that your answer is likely to be missing a significant component of the situation, and consequently the solution will be partial. You need the right type of expertise for the right type of problem.

Mobile Changes Everything?

As a prelude to a small webinar I’ll be doing next week (though it also serves to tee up the free Best of mLearnCon webinar I’ll be doing for the eLearning Guild next week as well, here’re some deliberately provocative thoughts on mobile:

According to Tomi Ahonen, mobile is the fastest growing industry ever. But just because everyone has one, what does it mean? I think the implications are broader, but here I want to talk specifically about work and learning. I want to suggest that it has the opportunity to totally upend the organization. How? By broadening our understanding of how we work and learn.

The 70:20:10 framework, while not descriptive, does capture the reality that most of what we learn at work doesn’t come from courses (the ’10’). Instead, we learn by coaching/mentoring (the ‘2o’), and ‘on the job’ (70). Yet, by and large, the learning units in organizations are only addressing the 10 percent. They could, and should, be looking at how to support the other 90, but haven’t seen it, yet there’re lots that can be done.

The bigger picture is that digital technology augments our brain. Our brains are really good at pattern-matching and extracting meaning. They’re also really bad at doing rote things, particularly complex ones. Fortunately, digital technology is exactly the opposite, so combined we’re far more capable. This has been true at the desktop, with not only powerful tools, but support wrapped around tools and tasks. Now it’s also true where- and whenever we are: we can share content, compute capabilities, and communication. And you should be able to see how that benefits the organization.

And more: it’s adding in something that the desktop didn’t really have: the ability to capture your current context, and to leverage that to your benefit. Your device can know when and where you are, and do things appropriately.

So why is this game-changing? I want to suggest that the notion of a digital platform that supports us ubiquitously will be the inroad to recognize that the formal learning is not, and cannot, be separate from the work. If we’re professionals, we’re always working and learning (as my colleague Harold Jarche extols us). If a new platform comes out that’s ubiquitous yet relatively unsuited for courses, we have a forcing function to start thinking anew about what the role of learning and performance professionals is. I suggest that there are rich ways we can think about coupling mobile with work.

Why do I suggest that courses on a phone isn’t the ideal solution? You have to make some distinctions about the platform. A tablet is just not the same as a pocketable device. It has been hard to get a handle on how they differ, but I think you do need to recognize that they do. For example, I’ll suggest that you’re not likely to want to take a full course on a pocketable device, however on a tablet that’d be quite feasible.

To take full advantage, you have to consider mobile as a platform, not just a device. It’s a channel for capability to reach across limitations of chronology and geography, and make us more productive. And more. So, get on board, and get going to more and better performance.

New Mobile Report Out

I’m happy to report that the eLearning Guild has just released this year’s mobile learning research report I authored for them (after doing the same last year). It’s free if you’re already a paid member of the Guild, which has other benefits (e.g. similar free access to other coming research reports, Thought Leader Webinars, etc). Combining my summary of the ‘state of the industry’ with the results of surveys of the Guild’s membership, it’s a snapshot of the state of mobile learning.

I should admit that there’s a bias in the report, in that the membership of the Guild is largely (though not wholly) corporate, and again largely US based. I suspect, therefore, that the global picture isn’t fully represented in the report. However, I do hope that the commentary does reflect general principles that are relevant regardless of context, though the fact of the market is that smartphones for instance are more distributed in the developed world than the developing world.

In the report, I make two points:

“What‘s clear is that it is time to move beyond the initial experimental stages and start thinking of mobile as a platform for organizational performance. … The time to get on top of mobile is now, as the market has matured to the point where we can see real benefits on a pragmatic basis.”

I believe mobile, as a platform, will have a transformative effect on the learning and performance workplace as it will elsewhere. As mobile delivers digital augmentation of our capabilities wherever and whenever, no longer just at the desktop, it will bring all the resources onto the table: performance support and social as well as augmenting formal learning. This is an opportunity for a game-change, where L&D can take responsibility for more benefits to the organization, and as a consequence be viewed more core to the business.

If you’re interested in what’s happening in mobile learning, this report is for you. If you’re active in learning & technology, I reckon eLearning Guild membership makes sense as well.

Mobile Work

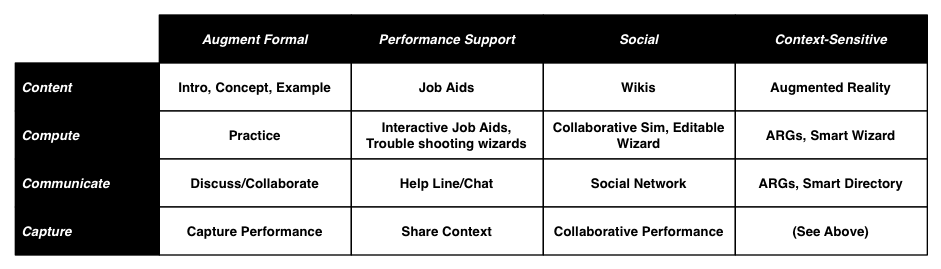

I’m regularly trying to do two things: explore mobile capabilities, and get folks to think more broadly about how we can support performance in the organization. I was asked to flesh out a proposed title for a stage at the upcoming mLearnCon, and thought about trying to map the 4C’s of mobile to the major categories of mobile work opportunities. It’s a slightly different take than my previous meta-mobile post where I looked at performance support, formal learning, and meta-learning.

In this case I’m looking at the 4 C’s by work categories. I see augmenting formal learning as one, providing performance support as a second, social media as a 3rd area, and the unique mobile contribution of context-sensitive support as a 4th area.

In this case I’m looking at the 4 C’s by work categories. I see augmenting formal learning as one, providing performance support as a second, social media as a 3rd area, and the unique mobile contribution of context-sensitive support as a 4th area.

I realize there are some problems in this, in that Social and Communicate are hard to discriminate (hence using the catchall phrase social network), and Capture is core to context-sensitivity. Alternate Reality Games (ARGs) don’t have to be social, but can be. And I hadn’t really thought through what context-sensitive computing and communicating might mean. Certainly you could have a focused directory that knows who knows about this context, and perhaps an app that presents different options for context-sensitive trouble-shooting or repair (e.g. knowing what device you’re liable to be working on), but I could be missing some options. And I’m not sure I’ve seen socially edited or maintained apps as opposed to content. Anyone? Anyone? Bueller?

So, as this is a first shot at this, I welcome feedback. What am I missing?