It occurs to me that we are too busy designing for learning, and that’s not what it’s about. It’s not about learning, as I often say. What is it about? It’s about doing. It’s about performance. So what does that mean?

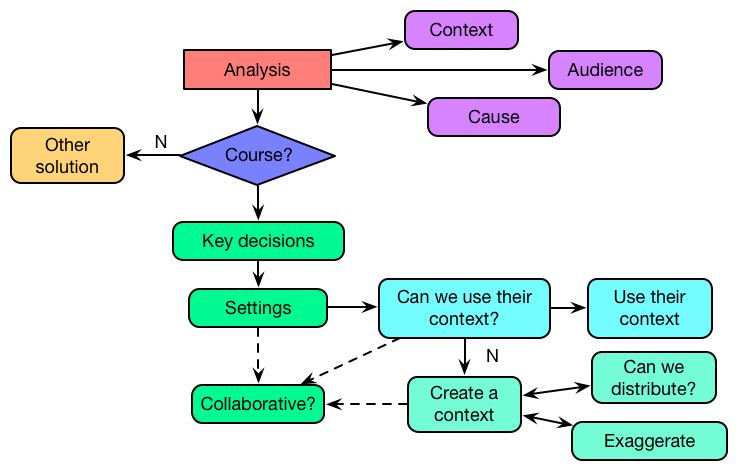

My backwards design process suggested looking at the desired performance, and then working backwards. This comes from a good analysis of the performance gap and determining the root cause of the difference between the existing performance and the desired one. The solution then is determining what can be in the world, and what has to be in the head.

Another way to be thinking about it is looking at how people really perform in the world. We need to be looking at when and how people need support, and figure out how we can bring support. People would rather not have to discover the answer if possible, and rather find it. Ideally, we are supporting finding the answer, but there are times when we haven’t anticipated the need, or it’s too unique to be worth investing.

The point here is that these ways of thinking about the problem come from thinking about meeting organizational needs, not about delivering learning services. They come from focusing on the doing, not the learning. And that’s a perspective organizations need.

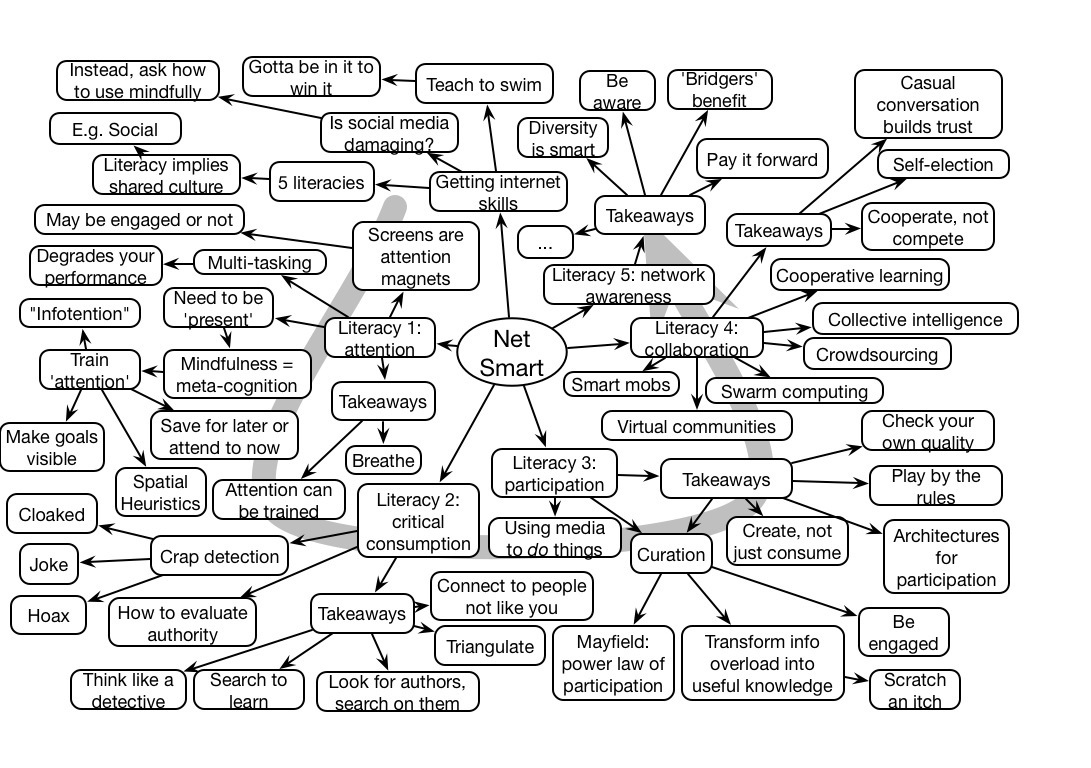

We do, however, need to be thinking about a broader picture. It’s not just doing the work, but it’s also about doing innovation, and continual capability development. So it’s not just putting in place elements that support optimal execution, but it’s also about putting in place the elements that support cooperation and collaboration.

The overall focus has to be supporting the needs of the organization. We need to be thinking about supporting the do, not just the learn. Are you designing for doing?