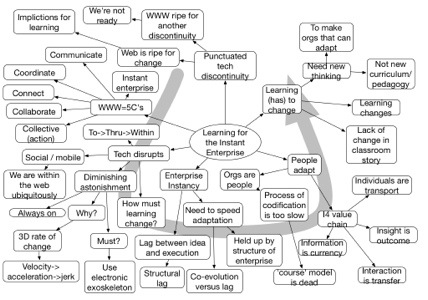

In a panel at #mlearncon, we were asked how instructional designers could accommodate mobile. Now, I believe that we really haven’t got our minds around a learning experience distributed across time, which our minds really require. I also think we still mistakenly think about performance support as separate from formal learning, but we don’t have a good way to integrate them.

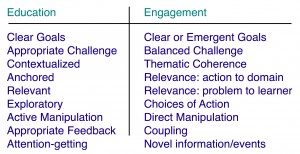

I’ve advocated that we consider learning experience design, but increasingly I think we need performance experience design, where we look at the overall performance, and figure out what needs to be in the head, what needs to be in the world, and design them concurrently. That is, we look at what the person knows how to do, and what should be in their head, and what can be designed as support. ADDIE designs courses. HPT determines whether to do a job aid (the gap is knowledge), or training (the gap is a skill). I’m not convinced that either really looks at the total integration (and willing to be wrong).

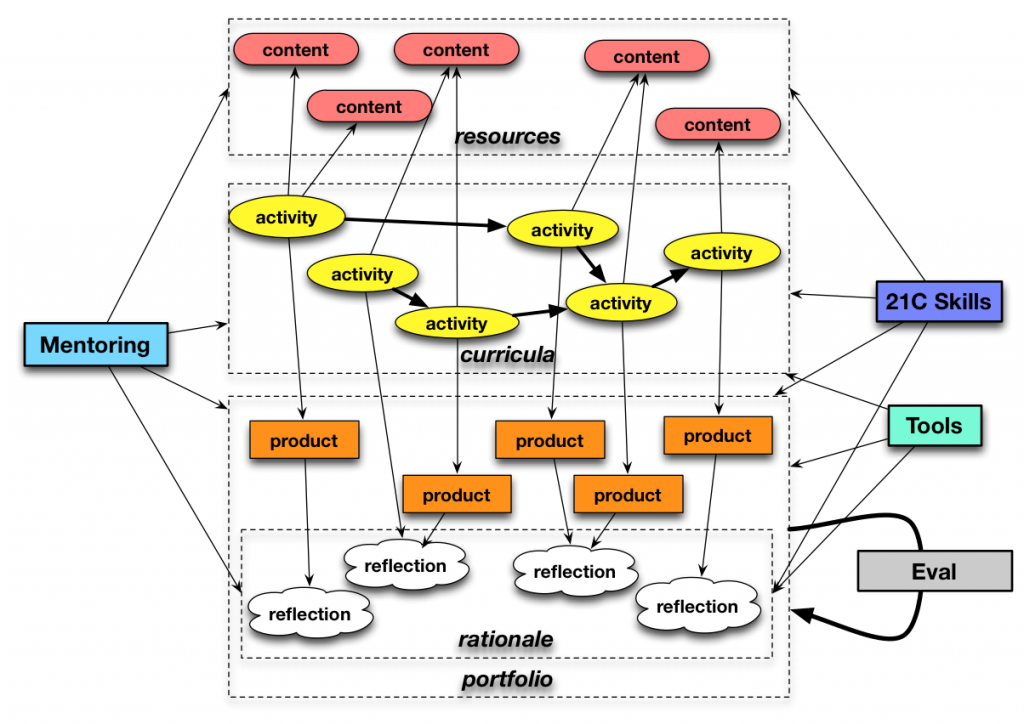

What was triggered in my brain, however, was that social constructivism might be a framework within which we could accomplish this. By thinking of what activities the learners would be engaged in, and how we’d support that performance with resources and other learners and performers as collaborators when appropriate, we might have a framework. My take on social constructivism has it looking at what can and should be co-owned by the learner, and how to get the learner there, and it naturally involves resources, other people, and skill development.

So, you’d look at what needs to be done, and think through the performance, and ask what resources (digital and human) would be there with the performer, the gap between your current learner and the performer you’d need, and how to develop an experience to achieve that end state. The notion is what mental design process designers may need going forward, and what framework provides the overarching framework to support that design process.

It’s very related to my activity framework, which nicely resonates as it very much focuses on what you can do, and resourcing that, but that framework is focused on reframing education to make it skills focused and developing self learning. This would require some additions that I’ll have to ponder further. But, as always, it’s about getting ideas out there to collect feedback. So, what say you?