Ok, so I’m being provocative with the title, since I’m not advocating the overthrow of training. The main idea is that a new area for L&D is facilitation. However, this concept also updates training. It’s part of what I was arguing when I suggested that the new term for L&D should be P&D, Performance & Development. So let’s start with that. We need to facilitate in several directions!

Ok, so I’m being provocative with the title, since I’m not advocating the overthrow of training. The main idea is that a new area for L&D is facilitation. However, this concept also updates training. It’s part of what I was arguing when I suggested that the new term for L&D should be P&D, Performance & Development. So let’s start with that. We need to facilitate in several directions!

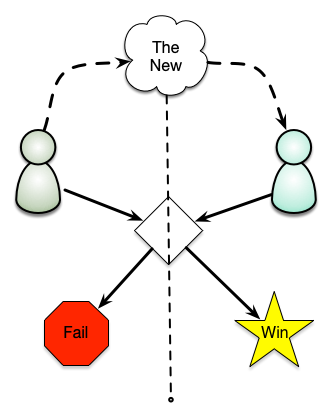

The driver behind the suggested nomenclature change is that the focus of L&D needs a shift. The revolutionary point of view is that organizations need both optimal execution and continual innovation (read: learning). In this increasingly chaotic time, the former is only the cost of entry, but it can’t be ignored. The latter is also becoming more and more critical!

A performance focus is the key to execution. You want to ensure people are doing what’s known about what’s need to be done. That’s the role of instruction and performance support. Performance consulting is the way to work backwards from the problem and determine the best interventions to do that optimization.

However, learning science is pushing us to recognize that we can do better. Information dump and knowledge test isn’t going to lead to any change in behavior. If you want people to be able to do, you have to have them do in practice. Which means the focus is on the practice and the feedback. That latter is facilitation. The clichéd switch from sage on the stage to guide on the side does capture it. So even here we see the need for facilitation.

It’s in the latter, however, where facilitation really comes to the fore. When we talk about development, we’re going beyond developing the individual. We are addressing the organization’s learning. And, as I’ve said, innovation is learning, just a different sort. What’s needed is informal learning.

And informal learning, while natural, isn’t always optimal. Habits, misconceptions, culture, and more can intrude. This is why facilitation may be even more key to success for organizations.

And, again, L&D should be the most knowledge about learning, because learning underpins both performance and development. Thus, if L&D is going to adapt, learning how to facilitate learning will be core. Facilitate really will be the new ‘train’.