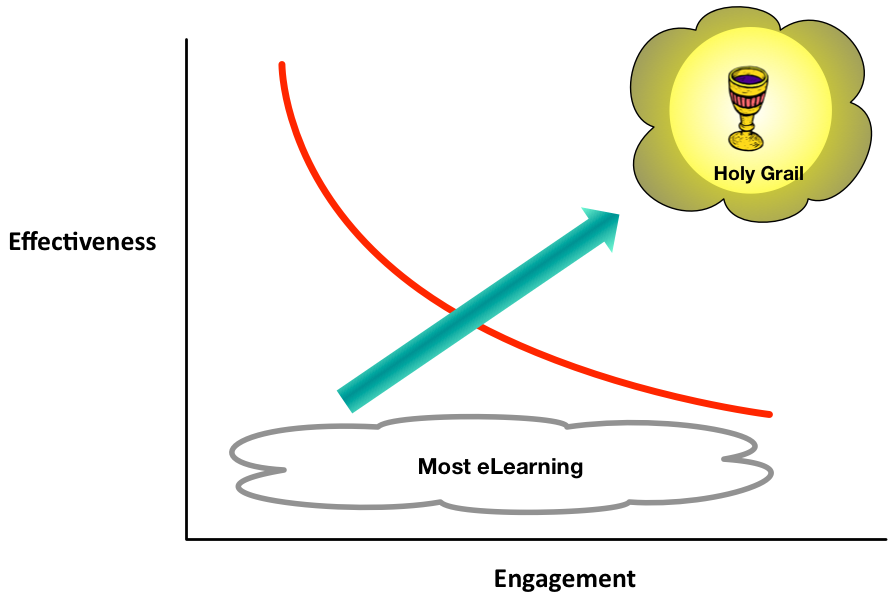

In a recent chat, a colleague I respect said the word ‘engagement’ was anathema. This surprised me, as I’ve been quite outspoken about the need for engagement (for one small example, writing a book about it!). It may be that the conflict is definitional, for it appeared that my colleague and another respondent viewed engagement as bloating the content, and that’s not what I mean at all. So I thought I lay out what I mean when I say engaging, and why I think it’s crucial.

Let’s be clear what I don’t mean. If you think by engagement it’s adding in extra stuff, we’re using a very different definition of engagement. It’s not about tarting up uninteresting stuff with ‘fun’ (e.g. racing themed window dressing on knowledge test). It’s not about putting in unnecessary unrelated imagery, sounds, or anything else. Heck, the research of Dick Mayer at UCSB shows this actually hinders learning!

So what do I mean? For one thing, stripping away any ‘nice to have’ or unnecessary info. Lean is engaging! You have to focus on what really will help the learners, and in ways that they get. And they do. And then help them in the ‘in the ways they get’ bit.

You need contextualized practice. Engaging is making the context meaningful to the learners. You need contextualization (e.g research by John Bransford on anchored cognition), but arbitrary contextualization isn’t as good as intrinsically interesting contexts. This isn’t window dressing, since you need to be doing it anyway, but do it. And in a minimal style (as de Saint-Exupery said: “Perfection is finally attained not when there is no longer anything to add but when there is no longer anything to take away…”).

You want compelling examples. We know that examples lead to better learning (ala, for instance John Sweller’s work on cognitive load), but again, making them meaningful to the learners is critical. This isn’t window dressing, as we need them, but they’re better if they’re well told as intrinsically interesting stories.

Finally, we need to introduce the learning. Too often we do this in ways that the learner doesn’t get the WIIFM (What’s In It For Me). Learners learn better when they’re emotionally open to the content instead of uninterested. This may be a wee bit more, but we can account for this by getting rid of the usual introductory stuff. And it’s worth it.

Now, let’s be clear, this is for when we’ve deemed formal learning as necessary. When the audience is practitioners who know what they need and why it’s important, then giving them ‘just the facts’, performance support, is sufficient. But if it’s new skills they need, when you need a learning experience, then you want to make it engaging. Not extrinsically, but intrinsically. And that’s not more in quantity, it’s not bloated, it’s more in quality, in minimalism for content and maximal for immersion.

Engaging learning is a good thing, a better thing than not, the right thing. I’m hoping it’s just definitional, because I can’t see the contrary argument unless there’s confusion over what I mean. Anyone?